“Phew, this is pretty steep”, pants the First Mate. “Let’s stop and admire the view.”

I’m glad of a break too. We are on our way up the steep hill leading to the Kristiansten Fortress overlooking the city of Trondheim. Unfortunately, our leg muscles don’t seem to be getting any sprightlier. Admittedly we are pushing the bikes as well.

“Look, you can see the Gamle Bybro bridge where we crossed over the Nidelva river”, I say, pointing to the bottom of the hill. “And the old town of Bakklandet with all its colourful houses. They look beautiful in the sunlight.”

“You just said ‘bridge’ twice”, says the First Mate. “Gamle Bybro means ‘old town bridge’, so you just said ‘Old Town Bridge bridge’. Just saying.”

Slightly refreshed, we push on, and before long we have reached the gates of the Fortress. A lot of people are milling around in the carpark outside. A notice says that it is the end of a mountain bike race. Not wanting anyone to get the idea that we chose to walk up the hill rather than pedal, I prod my tyres and mutter loudly about glass on the road and punctures. No-one seems very convinced.

The Fortress with its small museum is perched on the highest point within the walls. We learn that it was built in 1681 to protect the city against attack from the east. And not unreasonably, as 33 years later Trondheim was attacked by the Swedish.

“I’d forgotten that the Swedes and the Norwegians were at war”, I say. “It was during the Great Northern War when the coalition between Russia, Denmark-Norway and Poland-Lithuania were trying to limit Sweden’s power. Britain was even part of this coalition at one stage. I remember reading quite a bit about it when we were sailing around Sweden. They never said much about Norway though.”

“It says that Sweden attacked Trondheim in 1718, but the Fortress was too strong for them”, says the First Mate, reading from one of the panels. “Then the winter set in, and the Swedish troops, exhausted and without much food, had to beat a hasty retreat back to Sweden. Unfortunately, huge numbers of them died as they crossed the mountains on the way back. The Swedish went on to eventually lose the war at the Battle of Poltava, and had their vast empire drastically reduced.”

“A bit like Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow”, I say. “And Hitler’s too, for that matter.”

“Speaking of retreats, let’s beat one and go down to the city centre and have some lunch”, says the First Mate.

When we get to the main square, we discover that the annual Language and Culture Festival is in full swing. Small stalls representing a range of countries are arranged around the perimeter, each manned by people in national dress and selling food and arts and crafts from their respective countries. A large stage in one corner of the square has people dancing and singing. We decide to stop and enjoy the feeling of bonhomie everywhere.

“These samosas look good”, I say, stopping at the Nepalese stall. “I might get some for lunch. Want some?”

“I think that I might try some of those dumplings from the Polish stall”, says the First Mate. “The samosas might be a bit hot for me. Do you see the Eritrean national dress over there. So colourful!”

“We can eat our food at one of the tables”, I say. “And listen to the music that these Syrians are playing.”

“And Olav Tryggvason over there on that obelisk can keep an eye on us to make sure we put our rubbish into the bins”, jokes the First Mate. “He founded the city, so he probably wants to keep it tidy. He’s high enough to see everything that’s going on.”

In the evening, we walk along the breakwater in front of the marina. There’s a beautiful sunset.

We come to another statue.

“It says that it is Leif Erikson”, I say. “He’s thought to be the first European to set foot in America. Apparently he was converted to Christianity by Olav Tryggvason here in Trondheim, and told to go and convert the Greenlanders. Unfortunately he was blown off course, and landed up in America. He did eventually return to Greenland and fulfilled his task of converting them.”

“It seems that the statue was donated to Trondheim by the City of Seattle”, says the First Mate. “Apparently a lot of Norwegian emigrants settled there. They have an identical one.”

The next day, we visit the Sea Ivories exhibition at the University museum. In medieval times, before elephant ivory became available, ivory from walruses and whales was a sought-after commodity, and Trondheim became a thriving trade hub for it, both for raw ivory and for finished products.

We marvel at the intricate craftsmanship of the Wingfield-Digby crozier with St Olav amidst tree leaves painstakingly carved by a long-forgotten artisan. It was in the possession of the Wingfield-Digby family of Dorset who donated it to the British Government in lieu of inheritance tax.

The centrepiece of the exhibition are some of the Lewis chessmen, on loan from the British Museum. A hoard of these was found buried on a beach on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland in 1831, and are thought to have belonged to a wealthy merchant who was waylaid. It seems that they may have been made in Trondheim, as the style represent other ivory carvings known to have been made here.

The phone rings. It’s Tore from Riggmasters, calling about getting our shrouds renewed. He had been down a couple of days earlier and assessed the situation.

“We have a space now at our wharf”, he says. “If you can come into the canal tonight, we can do the shrouds tomorrow. There’s a bridge opening slot at 1920, so you could make that.”

Their wharf is in the canal through Trondheim, which requires us to go through the Skansen lifting bridge where the canal connects to the sea. It doesn’t give us much time to get back to the boat and get everything sorted for leaving our marina berth, but it is doable. We need to get the job done so that we can get on our way again.

We make it with ten minutes to spare, and wait for the bridge to open. Soon we are edging our way carefully up the canal, and tie up just in front of the RiggMaster workshop.

Tore starts on it in the morning, and by late afternoon we have new shrouds.

“I’ve tensioned them a lot tighter than the old ones”, he says. “You’ll notice that she will sail much more responsively now. If they are too slack, she’ll heel too much. You’ll probably get another knot of speed too.”

We plan to leave in the morning, and ring the bridge that evening to tell them we’re coming. If no one is waiting, they don’t open it. Just as we are about to leave in the morning, the phone rings.

“I am sorry”, a woman says. “We have a problem with the bridge. It won’t open. They are working on it now. We don’t know how long it will take.”

“The last time this happened, it took three weeks to open”, says Tore, overhearing. “You’ll just have to be patient.”

Three weeks! We have a flight booked in two weeks’ time, and we still have to put Ruby Tuesday to bed for the winter before then. Here we are trapped in the canal with no other way out! Panic!

The First Mate boils the kettle for a cuppa.

“Why did it have to be just now?”, she says. “Couldn’t it have just waited for another couple of hours before breaking down after we were through?”

At least the cup of tea tastes good. We kick our heels for a couple of hours, not quite knowing what to do. The phone rings. It’s the bridge lady.

“You’ll be very glad to know that they have managed to get the bridge working again”, she says. “You’ll be able to get the 1120 opening.”

Sighs of relief! At last we can make a bid for freedom. We cast off, wave goodbye to Tore and his crew, and motor past the island of Munkholmen before hoisting the sails.

“Apparently Munkholmen used to be used as a place for executions”, says the First Mate.

“Nice”, I say.

As we sail up Trondheimsfjord, the Hurtigruten ship comes up behind us. As it passes, two men lean over the rail at the back and wave.

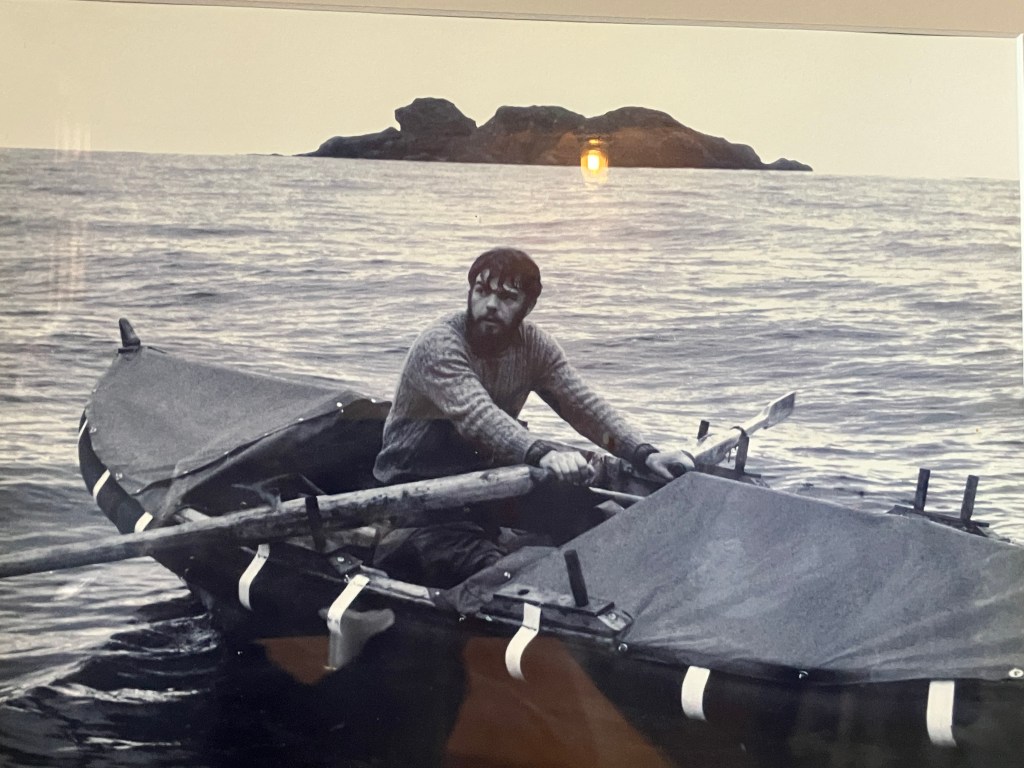

“I wonder who is in that little sailing boat we just passed?”, says the elderly gentleman to his companion. “I saw them in the harbour yesterday just close to where we were tied up. It had a British maritime flag. Surely they wouldn’t have come all the way from Britain? It’s a long way.”

“I don’t see why not”, says Mr Fairlie. “Apparently cruising in small boats is becoming quite popular these days, and not just for the rich and famous. The Royal Cruising Club was formed just nine years ago. And of course Norway is seen as an exotic destination. If they’ve come from Scotland, it’s not that far across the North Sea.”

“Well, I hope they have enjoyed themselves as much as we have”, says the minister. “And now, we have to get ourselves back down to Bergen. Hopefully Messrs Higgins & Baillie will re-join us there after they left us for their fishing trip in the interior. I wonder if they had much luck? And I am hoping there will be some letters there from my daughter Meg. I was disappointed not to find any there on the way up.”

“Well, I have to agree with you that it’s certainly been a very pleasant trip”, replies Mr Fairlie. “Friendly people, spectacular scenery, and interesting history. I wouldn’t mind doing it again some time. But I am looking forward to getting back to Edinburgh now.”

“Me too”, says the older man.

“We have enjoyed following your route too, great-great-grandfather”, I say, as I wave back at the ship disappearing into the distance. “We’ve seen places we probably wouldn’t have seen otherwise. But now we have to go our own ways. We’re leaving the boat here for the winter, and will continue northwards next year. Have a good trip back to Scotland.”

“They’ll never hear you”, says the First Mate, coming out of the cabin with a plateful of ham sandwiches. “Here. It’s just about lunchtime. I’ve made your favourite.”

—–

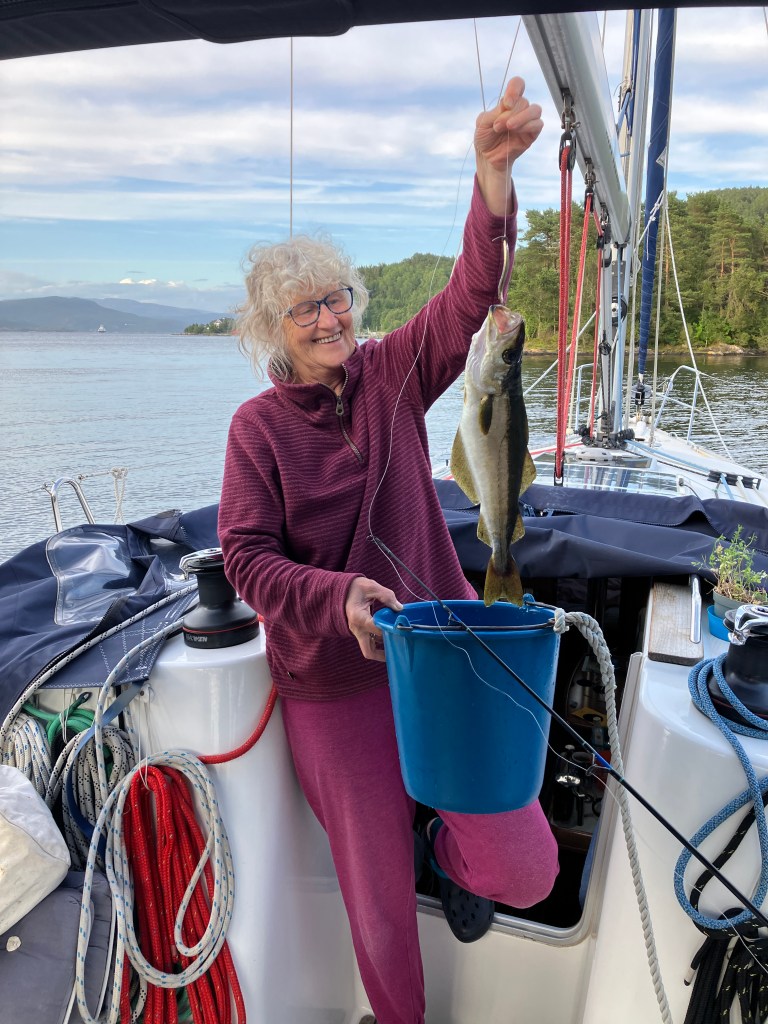

“I can see Hekla”, shouts the First Mate from the pontoon. “They’re just coming around the corner at the top of the inlet.”

Sure enough, the familiar shape of Bob and Fiona’s wooden ketch Hekla of Banff appears and negotiates her way majestically through the perches along the narrow channel to the harbour.

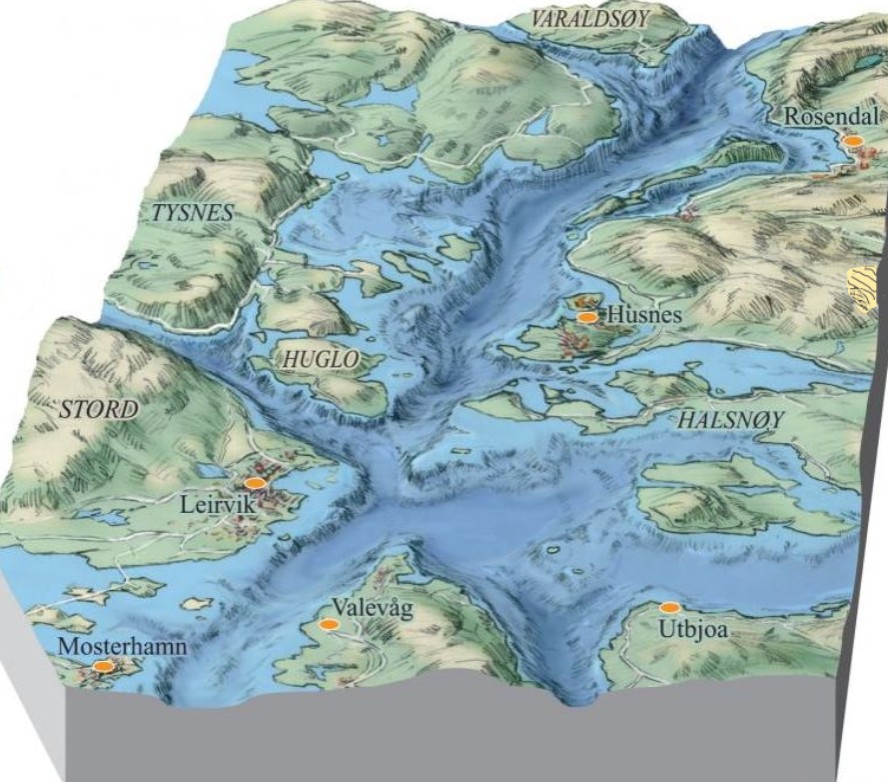

We are on the island of Hitra where we will be overwintering our boats. Amalia had arrived back in July, Aloucia just last week, and we ourselves in Ruby Tuesday had come earlier this afternoon. The Fabulous Four are all here now.

Over dinner, we catch up. It’s the first time we have seen each other since the sea-foraging event in Sweden back in May. Bob and Fiona had gained a lead of at least a week when we had travelled to Oslo, and were already in Bergen when we were still in Sweden. Then they had had to return to the UK for a couple of weeks to see family and we had caught up, but somehow our paths had not crossed since then.

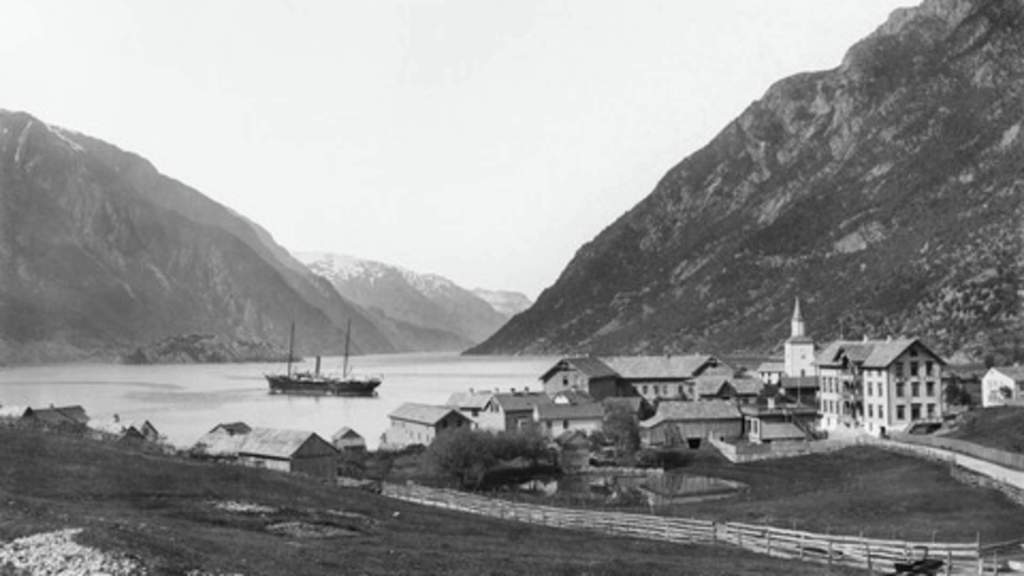

“We had a bit of a mishap when we left Hekla in Aurlandsfjord”, Bob tells us. “We were tied up to a pontoon there, and at some stage one of those high-speed ferries must have been too close. The wash from it rocked Hekla up and down, and somehow one of the gunwales got wedged under the pontoon and did quite a bit of damage. We’re looking to see if we can find a boatbuilder near here to repair it.”

“I can sympathise”, I say. “We had something similar happen to us in Lysefjord with those ferries. They should take more care.”

“Can I just interrupt to say that you can see the Northern Lights if you look up!”, Fiona suddenly calls out.

We sit spellbound watching the eerie green and purple lights of the Aurora borealis as the charged particles streaming from a solar storm reach the earth’s atmosphere. They writhe this way and that like giant glowing curtains before slowly fading away.

“Well, that was beautiful”, says the First Mate after they have gone. “We’re so lucky to see them.”

The next few days are spent preparing everything for the winter. Taking down the sails, packing away the spray hood, bimini and cockpit tent, changing the engine oil, replacing the oil and fuel filters, topping up the fuel tank, draining the cooling system and hot water cylinder. The First Mate stores all the clothes and other fabrics in vacuum packs and sucks the air out of them with the vacuum cleaner. It’s a big job.

In the midst of it all, Benjamin stops by. Benjamin is German, has a ponytail, and is wearing army camouflage trousers. He has a small boat tied up to the other side of the pontoon to us, and is waiting for some spare parts to arrive before he sets off back to Denmark where his partner lives. We end up talking politics.

“I voted for the AfD last time”, he says, flicking his ponytail behind them like a wild mustang. “We need a change. All the mainstream parties do is to talk, skirt around the issues, and make promises that they never keep. At least the AfD says it the way that it is.”

I ask him what he thinks about the Ukraine war.

“I hope that the Russians win”, he says. “Ukraine should never have provoked it by wanting to join NATO and the EU. It was quite predictable that Russia would respond in the way that it did.”

“But surely these days countries should be free to choose their own way forward”, I ask, somewhat taken aback. “Especially as it was a democratically elected government. If they want to be a member of NATO or the EU, why shouldn’t they be?”

“Nonsense”, he says vehemently. “That’s just Western propaganda. The reality is that small countries, especially those that are next to a major power like Russia, are not free to choose their own way, and have to consider what effect their choices will have on their more powerful neighbours. It’s just realpolitik.”

“Wow, he certainly does have very right-wing views”, says the First Mate later. “I haven’t met many AfD supporters before. Not who will admit to it anyway. Everybody that I have talked to says they don’t vote for them because of their neo-Nazi roots and ultra-right wing agenda.”

The day arrives for Ruby Tuesday to be lifted out and put on the land. We slowly motor over to the crane and position her in the narrow dock. Large bands are slipped around her and she is lifted out onto the apron to be hosed down to remove all the slime that has accumulated. Then she is transported to her place by the workshop for the winter.

“It’s good that we can stay on the boat while it’s on the land”, says the First Mate. “Not everywhere allows it. Now we can finish off all our remaining jobs.”

It’s our last night. Bob and Fiona have already left. Tomorrow we are to catch the 0720 bus to Trondheim, the train to Trondheim airport, then the flight to Copenhagen, and finally the train across to Malmö to collect our car.

“There’s supposed to be a blood moon tonight”, I say. “Let’s have dinner in the cockpit and watch it.”

We cook the last of our food and put on our fleeces. At first it is too cloudy, and we can see nothing. Then slowly the clouds clear to reveal the moon with a reddish tinge.

“If we were superstitious, we’d be thinking that war, plague and a royal death will follow”, I say. “Omens of the End Times.”

“We’ve had all those already”, says the First Mate. “What with the Ukraine war, COVID, and the Queen dying. Do you suppose there is more?”

“These days a blood moon is seen more as a time of revelation and renewal”, says Spencer, joining us. “A time when one chapter closes, and another opens.”

“I like that interpretation better”, says the First Mate.