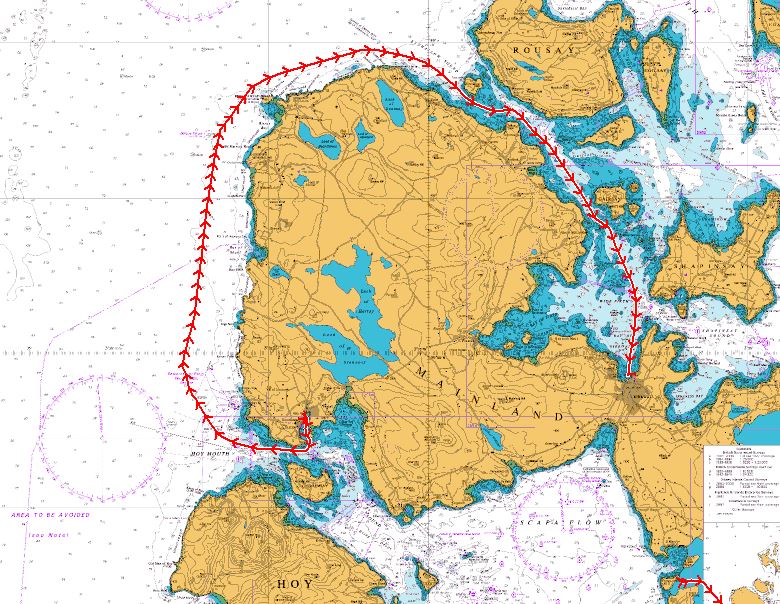

We decide to move on to Kirkwall. Sailing around Orkney is challenging, not least because of the complexity of the tidal flows around the islands. However, by careful timing, they can be made use of to help in making the journey quicker. Armed with the Tidal Atlas of Orkney and Shetland that I had purchased in Stornoway, I spend an evening working out the speed, times and directions of the flows along the clockwise route around Orkney Mainland and reckon that they can carry us all the way to Kirkwall by leaving Stromness on the last of the ebb tide at 0600 the next morning.

Sure enough, bleary-eyed, we are carried out of Hoy Sound by the west flowing current at around 9 knots. We pass the Experimental Wave Zone where there is research going on to generate power from tidal action, and head north. As expected, the tidal flow changes so that we are carried north to Brough Head lighthouse. The wind is from the south-west, directly behind us, so we only have the mainsail out, still making good speed. A pod of dolphins follows us for a short time then disappears. We arrive at Brough Head and turn to starboard, where the flow now takes us eastwards into Eynhallow Sound. From there, it is an exhilarating sail down the Sound at 10 knots dodging all the rocks, skerries and shoals inconveniently put in our way by some malign gamester.

We make it through safely and motor the last little bit into Kirkwall marina, where we tie up.

In the morning, we meet Dr Peter Martin, a former colleague of mine. Peter is now working for the Agronomy Institute at the University of Highlands and Islands in Kirkwall, and is doing research on bere, a traditional type of barley grown in Orkney, Shetland and Scandinavia. We drive out to his experimental plots on the Island of Burray. On the way, he tells me about bere.

“Bere was probably introduced from to Orkney in the 8th cent by the Norsemen”, he says. “It is a six-rowed barley, meaning that it has six rows of grains on each head compared to the two rows on most modern barley varieties. Because more grains are crammed on to each head, each grain is smaller than in modern varieties. It has a very short growing season – it is often the last crop to be planted and the first to be harvested – farmers sometimes refer to it as the 90-day crop.”

Peter and his team have been promoting the use of bere in a number of products including whisky and beer. The Bruichladdich distillery on Islay now has a line of whisky based on bere grown on Islay (the two distilleries on Orkney itself weren’t interested!), and there is a beer brewed from bere by the local Swannay brewery in Orkney. Meal is ground at the Barony Mills on the island of Birsay, and is made into bannocks and biscuits. Later, we buy a bere bannock to try it. It is fairly tasteless by itself, but is good with some strong cheese or the smoked mackerel we have in the fridge. We also buy some bottles of Scapa Bere – they are very drinkable with a slightly salty taste.

In the afternoon, it clears up and we decide to explore Kirkwall. The main feature dominating the town is St Magnus’ Cathedral, right in the centre. I had bought a copy of the Orkneyinga Saga while in Stromness which gives a good outline of the history when Orkney was ruled by Norway. St Magnus was one of the Norse Earls of Orkney, but perhaps uncharacteristically for a Norseman of those times, he was pious, gentle and kindly, and was more into singing psalms than waging war. Unfortunately, his co-earl Haakon (also his cousin) was just the opposite. Following a minor tiff between the followers of each one, they agreed to meet on an island in Orkney to sort things out, with each one bringing only two ships. Magnus, of course, kept his side of the bargain, but Haakon turned up with eight ships and captured Magnus. To keep the peace, Magnus offered to go into exile, but the Council of Chiefs decided that one Earl had to die. Haakon was pretty sure it wasn’t going to be him, so he ordered his standard bearer to kill Magnus. However, the standard bearer was so impressed by Magnus’ piety that he refused to do so, and Haakon had to get his cook to do it instead with an axe.

The story then moves to the next generation. Magnus’ nephew Rögnvald was granted his uncle’s part of Orkney by the King of Norway, but was resisted by Haakon’s son and successor, Paul Harkonsson, and the islanders. Rögnvald cunningly decided to win round the islanders by promising to build a magnificent cathedral, then he captured Paul and shipped him off to Caithness where he eventually had him killed. So Rögnvald got the whole of Orkney and the islanders got their cathedral, which was dedicated to Magnus, and everyone was happy. For a fleeting moment, a picture of current British politics enters my mind, but I dismiss it instantly as being an absurd comparison. At least, I think so.

We walk across the road to see the Bishop’s Palace, which was built for the first bishop, William the Old, at around the same time as the Cathedral. Apparently, King Haakon of Norway (not the same Haakon as above) died here on his way back to Norway after being defeated in the Battle of Largs. His remains were buried in the Cathedral temporarily until the weather improved, then were returned to Bergen.

Just next to the Earl’s Palace is the Earl’s Palace. There is a sign saying that tickets must be purchased to enter the palace itself, but walking around the grounds is free. Being the tightwads that we are, we decide on the latter and walk on. I suddenly notice that the short stout lady in charge of the little kiosk where the tickets are bought is locking the door and rushing over at top speed to the palace doors.

“She’s probably spotted someone who hasn’t paid and is rushing over to catch them”, I say to the First Mate. “I don’t fancy their chances when they get caught. She looks like one of Earl Haakon’s descendants!”

There is no answer. I look around, but there is no sign of the First Mate. The Ticket Lady reappears, followed by a rather crest-fallen First Mate. The thunderous look on the Ticket Lady’s face laves no doubt in my mind that she would like nothing better than having the miscreant by the ear, frog-marching her to the gate, and telling her not to come back. It’s lucky she is only as half as high as the First Mate.

“I just wanted to have a quick look around the door”, says the First Mate in response to my querulous look. “I didn’t think anyone would be watching.”

I consider pretending that she is a mad tourist talking to one of the trees and is nothing to do with me, but relent. She has always had a thing for houses with turrets, after all.

“Just as well she wasn’t the Earl”, I say instead. “I think I would miss you.”

The next day we take the bus down to see the Italian Chapel. This was built by Italian prisoners-of-war captured in North Africa in WW2 and brought to Orkney to build the Churchill Barriers to prevent enemy ships from entering Scapa Flow. While they were here, they decided they needed a church so put two Nissan huts end to end, lined the inside with plasterboard, and used various odds and ends for the interior fittings – the baptismal font is made from an old car exhaust, for example. Whether you are religious or not, it is difficult not to be impressed with the ingenuity and the skill involved in the artwork, and not to realise that we have more in common with other Europeans than we have differences.

A little bit further on is the Orkney Fossil Centre. Since reading of the geology of Orkney on the way over, I am keen to see some of the Devonian fish fossils that had been found in the old sandstones. A feeling of awe engulfs me as we peer through the glass cases at the beautifully preserved skeletons, now part of the rock, but which were once living creatures in a massive freshwater lake. I find it difficult to really appreciate how long ago they lived – 400 million years is a long time. The Devonian is called the Age of Fishes; even though primitive plants and animals were just starting to colonise the land, it was a huge diversity of fish that dominated the lakes and seas. Among these were the tetrapods – those with four limbs – some of which used these to clamber on to the land and to become the ancestors of all animals with four limbs, including ourselves. Even more awe-inspiring is that, besides limbs, these fish had already evolved many of the other basic structures that we now possess – a primitive backbone, a skull containing a primitive brain, a hinged lower jaw, enamelled teeth, two nose holes, lungs, and blood containing urea. Even the plates making up our skulls are exactly paralleled in some of these Devonian fishes. We are peering down at our own ancestors!

My mind drifts back to Hugh Miller, one of the early discoverers of these Devonian fish fossils, not in Orkney, but from the same Lake Orcadie sediments in Cromarty further south. We had come across him when we had visited Cromarty in our smaller boat a few years previously, and had visited the house that he had lived in. Interestingly, Miller was both a geologist of some note as well as being an evangelical Christian. Through his geological work, however, he began to realise that the Earth was very old – indeed, many millions of years old and not just a few thousand years. Even though it was before Darwin published his Origin of Species, Miller also recognised that some fossils were descendants of other ones, and that somehow they had ‘metamorphosed’ from one to the other, but couldn’t quite bring himself to accept that humans were part of the same process. Or could he? He tragically died on Christmas Eve 1856 by shooting himself after suffering from depression brought about, many believe, by the mental stress in trying to reconcile his biblical beliefs with his scientific discoveries. Why is it often too difficult to change one’s beliefs even when presented with hard evidence to the contrary, I wonder?

The next day, we take the bus to Ophir to visit the Round Church, the Earl’s Bu and the Orkneyinga Saga Centre. It drops us off in the village of Ophir, but it is a three-kilometre walk still further from there. Luckily it is a beautiful sunny day and it is a pleasure to amble along the quiet country lane down to the coast. Only one tractor passes us on the way.

We eventually arrive at the Saga Centre. It is a bit smaller than we expected, in fact so small that it doesn’t have any staff in attendance! There is a poster board display and a video that starts when you press a button. The video tells the history of the site in the 12th century. At that time, it was the Earl’s manor house (a bu is the main farm in the area), and the Round Church was built by the same Haakon mentioned above as a penance for having his cousin Earl Magnus killed.

As you did if you were any sort of self-respecting Norseman, he had a dedicated drinking hall built next to the church, the foundations of which are still visible today. The story associated with the drinking hall is that some years later, Haakon’s son Paul Harkonsson (now the Earl himself) invited one of his vassals, Svein Asleifarson (who later became known as ‘The Ultimate Viking’ for his bloodthirsty exploits) to his drinking hall for a bit of a Christmas party. Apparently drinking one’s self under the table had a bit of a code – it all had to be fair, and you couldn’t drink less to stay sober than your drinking partners, in case you took advantage of their state and killed them, I suppose. One of Paul’s men, with the intriguing name of Breastrope, suspected Asleifarson of trying to stay sober and challenged him to drink more. Asleifarson vowed to take his revenge on Breastrope for this slight on his prowess, and later, when he had a chance, cracked him over the head, almost killing him but not quite. Breastrope lashed out, but in the confusion killed one of Paul’s kinsmen by mistake before dying himself. Leaving this trail of carnage behind, Asleifarson then managed to escape through a skylight and rode off on his horse and eventually escaped to Tiree. Needless to say, he wasn’t invited to one of Paul’s parties again for a while.

“Phew, they were a bloodthirsty lot in those days”, says the First Mate. “And it takes a bit of keeping up with who was the son of whom, and which cousin killed which brother, and all the rest of it. My head hurts. Let’s get back to the boat and have a glass of wine.”

“As long as you don’t accuse me of drinking less than you”, I say. “Breastrope’s head also hurt a bit as a result of him saying that.”

When we get back to the Kirkwall marina, we find we are the only UK-registered boat on our pontoon. All the others are Norwegian. I wonder if it is a secret Viking invasion by the descendants of Svein Asleifarson to regain control of Orkney after Brexit and the UK disintegrates. As we walk past each boat, I have a quick check to see if I can spot any battle-axes and helmets with horns, but don’t see any. Perhaps they are hidden under the floorboards. I tell the First Mate to make sure our claymores are easy to reach in the night, and lock the door just to be sure. She looks at me strangely.

We leave Kirkwall the next day on the way down to Wick in Caithness, but decide to anchor overnight in East Weddel Sound between Mainland Orkney and Burray to break the passage. Again, we need to calculate the tides correctly to catch the east-flowing tide from Kirkwall to the island of Copinsay then the flow southwards.

We arrive in the Sound in the late afternoon and anchor near one of the rusting blockships that were sunk deliberately to prevent access by German submarines to Scapa Flow during WW2. Just in case there is still wreckage on the seafloor that might trap our anchor, we rig a trip line with a buoy floating on the surface.

I am conscious that it was here that the German U-boat U-47 under Kapitänleutnant Günther Prien had managed to slip through a narrow route between the blockships at high tide just after midnight, and in the glow of the northern lights had torpedoed the Royal Oak, one of the main British battleships in Scapa Flow. He had actually fired three torpedoes at the Royal Oak – the first had hit but had caused little damage and the crew on board had thought it was some internal explosion, the second missed altogether, and it was only the third that struck amidships and did the damage. The ship sank in 13 minutes, with a total of 834 men losing their lives. Amazingly, amid the confusion, the U-47 managed to escape out the same way it had come in. It is not lost on me that our own track would have crossed the track that the U-47 had taken.

Although it was a bit like shutting the stable doors after the horse had gone, Churchill subsequently ordered the construction of concrete barriers across the gaps between many of the islands, which are still there to this day. Although this blocked off sea routes, it transformed society on the islands, linking people together much more closely than before.