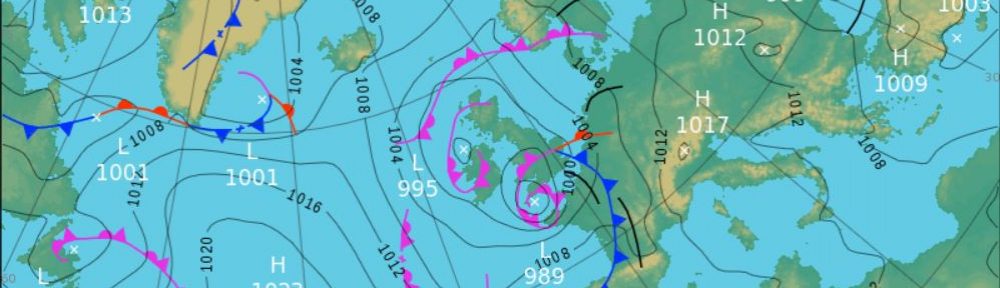

We leave Terschelling at 0600 on the dot, and catch the last hour of the outgoing tide that sweeps us out into the North Sea before it changes direction and begins to carry us eastwards. We have a 75 mile sail in front of us, and need all the help we can get to minimise the time. The wind is from the north and on our beam, but with the long period of northerly winds we have had over the last week, there is a significant swell from the side, and we wallow through each successive wave. It is not comfortable, and we both start feeling queasy.

Before long, Terschelling is fading into the distance. Other Frisian islands with the weird and wonderful names of Ameland, Shiermonnikoog, Rottumerplaat, Zuideruintjes and Rottumerroog appear and disappear in the haze. We would love to visit them, but all are too shallow for us to enter their gats and harbours.

After a hard day of sailing, we eventually arrive in Borkum harbour. There is only one pier for visiting yachts, and we need to raft up again. There is a strong cross-wind, and manoeuvring Ruby Tuesday isn’t easy. We select another boat of similar size and edge close in to it, but a sudden gust of wind pushes the bow round more than our stern. I frantically try and use the bow-thrusters to avoid our anchor from scoring their side, but the gust is too strong. A disaster looms. Luckily the owner of the boat has seen the danger and is waiting to fend us off. The anchor misses by centimetres and we glide alongside, fenders absorbing the shock and protecting each boat from damage. Ropes are thrown across from bow and stern, are threaded through cleats, and then returned – we are secure. Our new neighbours are from Norway, they have been to the Caribbean, and are now waiting for southerly or westerly winds to take them home again.

As we are now in Germany and not Holland, I put up the plain yellow Q-flag to indicate that we still need to clear customs and immigration formalities. I am not sure it is needed, but technically we are in a new country, and with the UK no longer in the EU, I reason that it is better to be safe than sorry. The Germans like their rules.

“The flag looks like it’s upside down”, jokes the First Mate.

“How can a plain yellow flag be upside down?”, I say.

But she is right. I have tied the little loop at the bottom and the long tail at the top without thinking. It’s soon fixed.

The next day we cycle into Borkum town and head for the beach.

“Oh, look”, says the First Mate. “There are some strandkorbs. I have always liked them. They are great for sitting on the beach when it is windy.”

Strandkorbs are basically two-seater park benches, but have evolved into quite elaborate structures that can be tilted backwards and forwards, rotated to face away from the wind, have a canopy that can be pulled down against the sun, folding foot-rests, folding shelves for drinks, and storage drawers underneath.

“The most expensive with all the extras can cost nearly €3000 new”, she continues. “Made of teak, with porthole windows, cushions, you name it. Germans think it is the pinnacle of sophistication to own one. But you can also rent them by the day or by the week. See, these ones cost €12 a day.”

I had always been amused by them. I had seen photos of old couples sitting in them completely wrapped up on cold, windy and overcast days, stoically determined to have a day at the beach in spite of the weather. I can see the point of them, but why not just wait for a good day?

“Often you can have sunny warm weather here, but there might be a strong wind lifting sand from the beach”, says the First Mate, a little defensively. “Strandkorbs allow you to enjoy the sunshine while protected from the wind.”

“I can’t imagine a family with parents and kids all cramming into them”, I say.

“Ah, but they do”, she retorts.

We buy some filled rolls and sit in the small park opposite the train station to eat them. A little girl is fighting with her brother for a scooter. Their exasperated mother grabs the scooter and tells them both to behave. A man with bags of cat litter stacked up on the carrier of his bike parks it and comes and sits on the next seat. Opposite, a woman sits with a laptop on her knees and talks animatedly into her mobile phone. There is a toot, and the small train from the harbour arrives, disgorging its passengers. Two horses wearily plod past pulling a wagon-load full of tourists.

“Life in Borkum, eh?”, says the First Mate.

“Come on”, I say, swallowing the last of my roll. “Let’s get going. We haven’t got all day.”

We find a cycle path leading from the town beach, following the sand line around the northern coast of the island.

Eventually it leads away from the beach and though a lush green woodland.

At one point, we see a sign pointing to the FKK beach. There is even a bus stop called FKK Beach.

“Shall we go there?”, I say. “Perhaps we can have a swim?”

“I didn’t bring my swimming costume”, says the First Mate.

It’s as good an excuse as any. We cycle on.

The path circles round to the south and we find ourselves cycling back along the southern dyke just as we did in Terschelling. On the landward side are fertile polders, and on the seaward side marshlands growing rushes which give way to the mudflats. There is a strange beauty.

In the morning, we set off for Norderney. As with Terschelling, we catch the last of the ebb tide to take us out to the North Sea, and then the flood tide to take us eastwards. This time it is only 35 miles, but the swell has persisted, and the wind is strong. We have a good sail, but there is a fierce chop and it is not smooth.

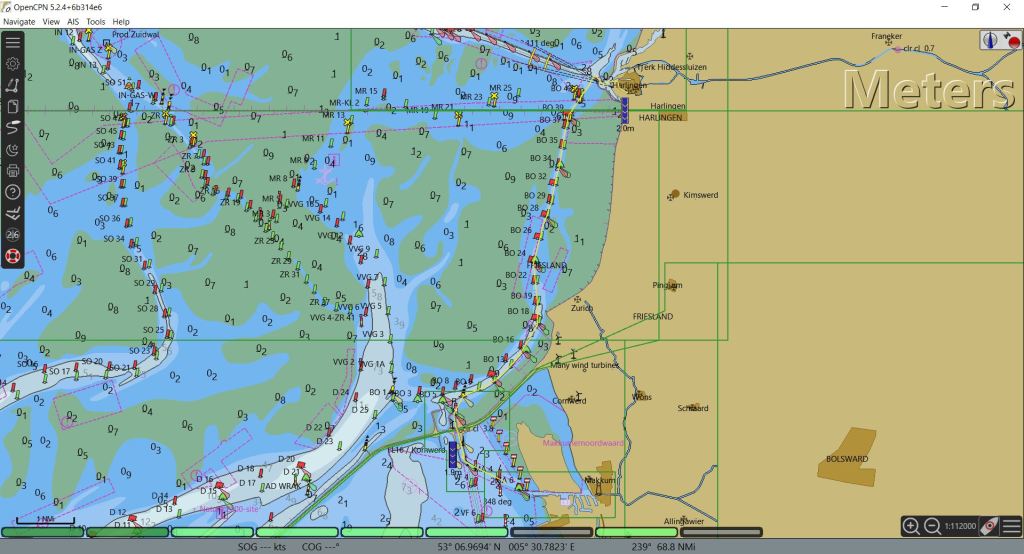

We approach Norderney. There are two channels into the harbour. One, the Schlucter, is from the west, and therefore is the natural one that we would take. The other, the Dovetief, is from the east. Both are relatively shallow, marked on the charts as 2.6 m at low water. The four slight problems are that our keel is 2 m deep, that we are approaching just after low water, in choppy conditions, and the Schlucter is very narrow with drying sandbars on each side. Get it slightly wrong, and we could end up grounded. The Dovetief is wider, with more margin for error, but would entail a long detour eastwards to enter it, then back again.

“Why don’t you call the harbourmaster at Norderney and ask him about the depth in the Schlucter?”, says the First Mate, anxiously. “He might be able to advise us.”

I manage to get through to him.

“It could be touch and go for you, especially in choppy conditions”, he says. “I would wait an hour for the tide to rise a bit more, if I were you, then you should have enough to get through. Follow the red buoys, keeping them to your port side. However, remember that the S6 buoy has moved and you need to keep it on your starboard and not your port.”

We reach the outermost buoy, the S2, and decide to anchor there for an hour. The bottom is sand and the anchor sets well, but with a choppy sea with long swells rolling in from the North Sea, it is not comfortable. Ruby Tuesday pitches up and down, and we both feel queasy. The information about the S6 buoy being in the wrong place also does not add to our confidence.

Eventually the hour is up, and we motor gingerly in, counting the red buoys, S4, S6, S8. As advised, we are careful to go on the wrong side of S6. At one stage, the depth reads 0.8 m below the keel. We breathe in, and slowly it increases again: 1 m, 1.1 m, 1.2 m. We are past the worst. Later I calculate that the extra depth that we gained by waiting an hour is 30 cm. We probably could have made it with only 50 cm under the keel in calm conditions, but with the pitching and tossing of the waves, we could have easily hit the bottom. Better to be safe than sorry.

In the evening, we sit in the cockpit and enjoy the soft golden glow of the setting sun. Suddenly the peace and calm is shattered by the piecing shrieks of a flock of oyster-catchers on the opposite bank. Something has upset them. We watch in fascination as they set upon a solitary black-headed gull in their midst. On one of the posts in the water, a single oyster-catcher seems to be directing operations. Again and again, the attackers dive bomb the gull, who runs this way and that trying to escape. Eventually it gives up and flies away. The shrieking dies down and peace returns.

“Internecine warfare in the bird world”, I say.

“I think it is over territory”, says the First Mate. “The oyster-catchers must think they own that piece of land over there, and try and keep any other bird species away from it.”

I am not so sure. We didn’t see any oyster-catchers there earlier in the day, and after they had proved their point with the gull, they all left. The next day we see a huge flock on another promontory. They don’t seem to be wedded to a specific territory.

In the morning, we unload the bikes and cycle into the town centre. We find the Tourist Information in a stunning building called the ConversationHaus and obtain a map of cycle tracks over the island. Outside there is a band playing “Time after Time”. We sit and listen, but it is their last song, and they pack up.

We cycle out of the town and find a cycle track that takes us around the island. From one of the dunes we have a fantastic view over the rugged interior. It looks wild, but there are cycle tracks criss-crossing it.

We eventually reach the lighthouse in the middle of the island and stop at the restaurant there for lunch.

The track eventually comes to the southern dyke and takes us all the way back to the marina. I am conscious that Erskine Childers’ spy novel Riddle of the Sands was set here, and try and imagine Arthur Davies wending his way in his Dulcibella through the narrow channels and fog to Memmert island and the waiting Captain Dollmann in his yacht plotting to invade Britain in WW1.

“Look!”, says the First Mate suddenly. “There’s a plane taking off.”

A small aircraft is taxiing along the runway of the tiny airport in the centre of the island. We watch it climbing until it disappears into the clouds.

“It’s probably heading back to the mainland”, says the First Mate. “They have regular flights back and forwards.”

Suddenly there is a swishing sound above us and we see half-a-dozen parachutists descending rapidly in our direction, their colourful parachutes contrasting with the white of the clouds. The same small plane is coming back to land again.

“They are probably British paratroopers come to attack Dollmann’s Medusa”, I say. “Carruthers must have ordered it.”

She looks at me strangely.

“You have a weird imagination sometimes”, she says.

I notice that a pattern seems to be emerging for us on these islands. We tie up in the harbour, explore the town on the western side of the island, then cycle eastwards to see beautiful sandy beaches, small villages, and woodland until we reach the nature reserves on the eastern end of the island, then return along dykes with polders on one side and the muddy flats of the Wadden Sea on the other.

“I told you that once you have seen one of the Frisian Islands, you have seen them all”, says the First Mate.

And yet, somehow, each one does have its own character. Terschelling is the summer playground of the Dutch, Borkum is the same for the Germans, and Norderney is supposed to be the new Sylt, the island playground of the international jet set in the North Frisian Islands.

“I haven’t seen any rich and famous yet”, I say.

“No, nor have I”, says the First Mate. “They are probably all hiding in their beautiful houses overlooking the beaches, trying to avoid the peering eyes of the riff-raff like us. And all those small planes we saw parked at the airport probably belong to them.”

In the evening, we meet Jost and Marina for drinks. We had first met them in Borkum when they tied up behind us, and then again here in Norderney when they had rafted up next to us temporarily before being allocated a proper berth. Josh is born and bred in Friesland in Holland and is financial controller at a large school, while Marina is from Amsterdam and is a university lecturer.

They proudly tell us something of the history of Frisia.

“The area was first settled in Roman times, when the people lived on man-made hills on the Wadden Sea mudflats to stop being swept away by each tide”, says Jost. “The Romans considered them a bit primitive as they hadn’t developed any agriculture and lived on a subsistence diet.”

“It’s interesting that the area eventually developed the Frisian cow, the highest milk production cow in the world, and yet were so primitive in those times”, I say.

“Yes, but the cows did exist even back then, but were kept by a different Frisian tribe further inland”, says Marina. “It’s thought that people from Hesse came to Frisia with their black cows and crossed them with the white cows that were in Frisia at the time, which eventually become the modern-day Frisian.”

“My sister lives in Friesland In Germany”, says the First Mate. “It’s interesting how Frisia seems to be split between both the Netherlands and Germany nowadays.”

“Yes, the Frisians were always more interested in their farming than in warfare”, continues Jost. “They never really existed as a separate country as such, but were invaded by various other peoples, including the Vikings, the Franks, the Saxons, you name it. In the Middle Ages, they became part of the Hapsburg Empire, but they didn’t like that too much, so they did revolt, and joined the Dutch republic when it was formed in 1577.”

“What about the Frisian language?”, I ask.

“There are actually three main Frisian languages”, says Marina. “West Frisian, Saterland Frisian and North Frisian. But there are also a lot of dialects, many of which are not mutually intelligible. It’s pretty complicated. Frisian is also the closest Germanic language to English, with a lot of similarities particularly with the English spoken in Norfolk. Probably due to the trade links they had back then. Some Frisians even joke that London is a suburb of Frisia!”

“In Frisian, we say tsiis for cheese and tsjerke for church, for example”, says Jost. “Old English and Old Frisian were very similar, but English and Frisian are two separate languages nowadays, mainly because of the influence of other languages – English by the Norman French, West Frisian by Dutch, and North Frisian by German.”

I shiver. It is getting late, and we are the last customers left in the bar. The moon has risen and casts a streak of light across the water. We drink up, put on our jackets and stumble back to our respective boats. It has been a fascinating insight into a small part of Europe that I knew little about. Frisia is not just about cows.