“Have you seen my rain-jacket?”, I ask the First Mate. “I took it with me into Umeå on the bus yesterday, and I am worried that I might have left it somewhere. It’s just a new one, and it would be a pity to lose it.”

“No, I haven’t seen it”, she says. “Have you looked in your rucksack? You normally keep it there.”

“Of course I have”, I say. “It’s the first place I looked.”

We are still in Umeå, waiting for favourable winds to continue our voyage north. Southwest winds are forecast for the morning, so we are planning to leave then.

We search for the jacket everywhere in the boat, but there is no sign of it. I can’t even remember where I saw it last.

“It’ll turn up”, says the First Mate hopefully. “Anyway, you’ll never guess who I met this morning in the club house.”

“A German couple, Axel and Carmen”, she continues. “They are friends of Axel & Claudia who we met in Dover all those years ago, and whom we last saw in Kalmar last year. They saw our name on the list of boats staying here and recognised it from something that Axel & Claudia had said. Isn’t that a coincidence?”

“It’s certainly a small world”, I agree. “But when you think about it, it is probably not so much of a coincidence, as there are only certain places that sailors can go, and the chances are that you will meet someone you know there, or at least someone who knows someone you know. It’s like a large network. It’s quite nice in a way.”

“They certainly have been very helpful”, she says. “Look, here’s a list of all the nice places that we have to visit as we go north from here. And lots of information about each, too.”

The winds in the morning are from the southwest, and we prepare to leave. My rain-jacket still hasn’t turned up.

“I’m sure it will be on the boat somewhere”, says the First Mate. “I don’t remember you wearing it in town, and I can’t see how you would have left it on the bus. You just haven’t looked hard enough.”

She’s probably right.

“I’ll just go and pay our marina fees”, I say.

The first thing I see on entering the clubhouse is my jacket hanging on a peg. Then it all comes back. I had put it on to brave the winds and rain a few days ago, and had hung it up hoping it would dry. And had forgotten all about it.

“Do you think senility is setting in?”, says the First Mate as we leave. “It happens to people your age, you know.”

“Well, I can still do the crossword every morning”, I say. “When I can’t do that anymore, I’ll know that I am past it.”

We reach the small harbour of Ratan in the afternoon and tie up alongside to a wooden wharf.

One of Ratan’s claims to fame is that it was here that the scientists Anders Celsius and Carl Linnaeus measured the change in sea level in1774 over a period of time and calculated the rate at which the land was rising due to isostatic rebound. An inscription on a lichen-covered rock, now some 2½ metres above the waterline, still remains. Their only error was that they thought that the water level was decreasing due to evaporation, rather than the land rising.

“Anyone can make a mistake”, says the First Mate.

Ratan was also the site of a battle between the Russians and the Swedes in 1809. Even though the Russians had technically won, their forces were so depleted that they withdrew, which gave the Swedes a stronger bargaining power in the negotiations. This had the result of the border between Russia and Sweden being drawn where the present day border is between Sweden and Finland, rather than further west that the Russian Tsar had originally demanded.

We seem to have synchronised our passages with Gavin and Catherine of Saluté whom we had met several times before on the trip up to Umeå. They are also aiming for the north of the Bay of Bothnia, so we decide to travel together where possible. It’s nice to have company.

The next few days we wend our way up the coast north of Umeå heading for Luleå, sailing in the afternoons, finding the next small harbour to stay in overnight, then exploring where we are in the mornings. Then repeating the pattern.

“What a fantastic view”, says Catherine, as we puff our way to the top of a hill with a lighthouse perched on top. “I wouldn’t mind coming back here sometime.”

We have overnighted in the tiny harbour at Bjoröklubb. At least, Saluté has, but it was borderline depth for Ruby Tuesday and we had tied up to the SXK buoy further into the bay.

“I know a lighthouse keeper’s job is a lonely one” says the First Mate over lunch in the small restaurant at the base of the lighthouse. “But at least the view would have compensated a bit.”

We reach the industrial city of Skellefteå, with its skyline of chimneys belching steam and worse. In the evening we have dinner at the marina restaurant and listen to a live band singing Irish ballads. Apparently the owner is Irish.

In the morning we push on and reach the Piteä archipelago. We find a sheltered bay on the south coast of the island of Vargön and drop anchor. It comes on to rain. After dinner, I start reading my new book, Being You: a New Science of Consciousness, by the neuroscientist Anil Seth.

In it, he argues that our perception of reality is in fact a ‘controlled hallucination’. Our brains are ‘prediction machines’, constantly generating ‘best guesses’ of what causes its inputs from the senses. From these, it constructs a ‘reality’ that is continually tested against new sensory information and modified if necessary. Our emotions don’t, in fact, control our reactions to something, instead it is the other way round – our reactions cause the mind to construct an explanation for them. Feeling sad doesn’t make us cry, for example; instead we cry, and the brain’s explanation for this is that we are sad.

It’s compelling stuff. Seth has researched this area for several decades, and has come to these viewpoints from the various phenomena he has observed. One example he uses is the photo of “The Dress” that swept the internet some years ago, and which some people see as white and gold, and others as blue and black. Which is real? In fact, neither, says Seth. Objects don’t have specific colours – they are just something that our brains have constructed based on our personal history and previous experiences.

“Fascinating”, says Spencer, reading over my shoulder. “But have you considered that there are other types of consciousness besides humans? We animals have it as well, you know. I, for example, am self-aware, can perceive the outside world, have subjective experiences, and construct narratives about all these things. Octopuses also seem to have a sense of self. This was well known in the Middle Ages when animals were prosecuted, convicted and punished for doing something wrong (according to human laws!). Their only thing the people then didn’t realise was that animal minds are very different from human minds. You have absolutely no idea what it is like to be a spider, or an octopus, or a bat, for example.”

“Or another human, for that matter”, I say. “But I have to assume that other people think more-or-less the same way as I do, or else I wouldn’t get very far.”

“Ah, social consciousness”, he says. “True. It’s called the Theory of Mind. You have perceptions of how other people perceive you. But some animals have that too.”

We reach Luleå the next afternoon. Two massive ice-breakers greet us as we enter. Strong winds and rain are forecast for two days, so it looks like we will have to stay put for a while.

“We should go and see the old church town while we are here”, I say, consulting TripAdvisor. “It’s designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site.”

We catch the bus out to Gammelstad to the northeast of Luleå. Gammelstad used to be Luleå and was a bustling port, but due to land rise the port disappeared so it was decided to build a new port and call it the same name of Luleå. The old Luleå was then called Gammelstad, or Old City.

“Could you run that past me again?”, says the First Mate. “You lost me at the ’used to be Luleå’ bit.”

“Don’t worry”, I say. “Suffice to say that Gammelstad was an old church town, or kyrkstad. Because people lived in remote areas, they couldn’t travel to church on a regular basis, so the churches set up a cluster of small cottages around them for people to come every so often to do their churchy business, such as baptisms, marriages and the like, and they would stay in the cottages. It was one of the conditions that the cottages couldn’t be lived in permanently. Apparently there used to be 71 kyrkstad in Sweden, but now only 16 are left. Gammelstad is the best preserved.“

“I bet the young people also saw it as an opportunity to meet future partners”, says the First Mate.”

We wander around the small village. Judging from the lavish furnishings of the church, there was obvious wealth in the area from fur trading and salmon fishing. In typical fashion, there is even a Separatists cottage, where those who disapproved of the new church books worshipped separately from the rest of the congregation, and eventually split away completely.

“I think we should hire a car tomorrow”, I say over breakfast the next morning. “We can drive up to Jokkmokk to see the Sámi museum there. We can also cross the Arctic Circle.”

“Good idea”, says the First Mate. “There’s also the Storforsen Falls which are worth seeing, apparently. They’re on the way. I’ll see if I can find a car rental place near here.”

We set off early the next morning in a hired Citroën C5. Everything is electronic. It can even work out when I get too close to the centre line or the hard shoulder line and flashes a warning. The one-lane highway means that it happens often.

“It’s a bit over the top”, says the First Mate. “It’s almost as though they have to keep on thinking of new ideas to stay ahead of the competition. Anyway, nagging you is my job. Hey, watch that pothole. You’re far too close.”

Despite the constant flashing warnings and the stream of instructions from the First Mate, I somehow manage to get us to Storforsen Falls.

They are impressive, especially as there has been a lot of rain in the last week.

“The book says that they drop 82 metres and are one of the largest in Europe in terms of water volume”, says the First Mate. “Their average flow is around 200 cubic metres per second, but it can get as high as 1200 m3/s, especially in midsummer. Come on, let’s walk up to them.”

We stand on the safety platform and look over at the raging torrent as it thunders over the rocks, the air moist with the spray. A forlorn life ring hangs nearby, but it is a token gesture – anyone falling into the maelstrom would be carried downstream in a flash and smashed against the rocks. They used to float logs downstream on it, but it is difficult to see how they would be anything other than matchwood when they arrive at the bottom.

We resume our journey.

“Stop, stop!”, shouts the First Mate suddenly. “There’s a mother reindeer and her calf crossing the road. Let me get a picture.”

We pull off to the side of the road. The car tells me to get back into the driving lane. I gain perverse pleasure in ignoring it. The humans are still in control. For the moment.

A little further on, we come to a large sign proclaiming that we are about to cross the Arctic Circle.

“We have to stop here”, says the First Mate. “And get the photo.”

“The Arctic Circle is the lowest latitude at which the sun never sets on midsummer day and never rises on midwinter day”, a placard tells us. “It is defined by the Earth’s inclination, which is influenced by the sun, the moon and the planets. It’s not constant, but moves northwards and southwards in a cycle of 40,000 years.”

“It must be a bit of a nuisance having to move this sign all the time to keep up with where the Circle is”, jokes the First Mate, as she takes the photo.

Her jokes seem to be getting better.

We eventually arrive in Jokkmokk.

“Jokkmokk comes from the Sámi language for ‘river’s curve’”, says the woman in the Tourist Information. “It’s an important place for the Sámi people of Sweden. The Sámi parliament has an office here, and the Sámi museum is just opposite the church. There’s also a restaurant, so you could have lunch there. The fish is good.”

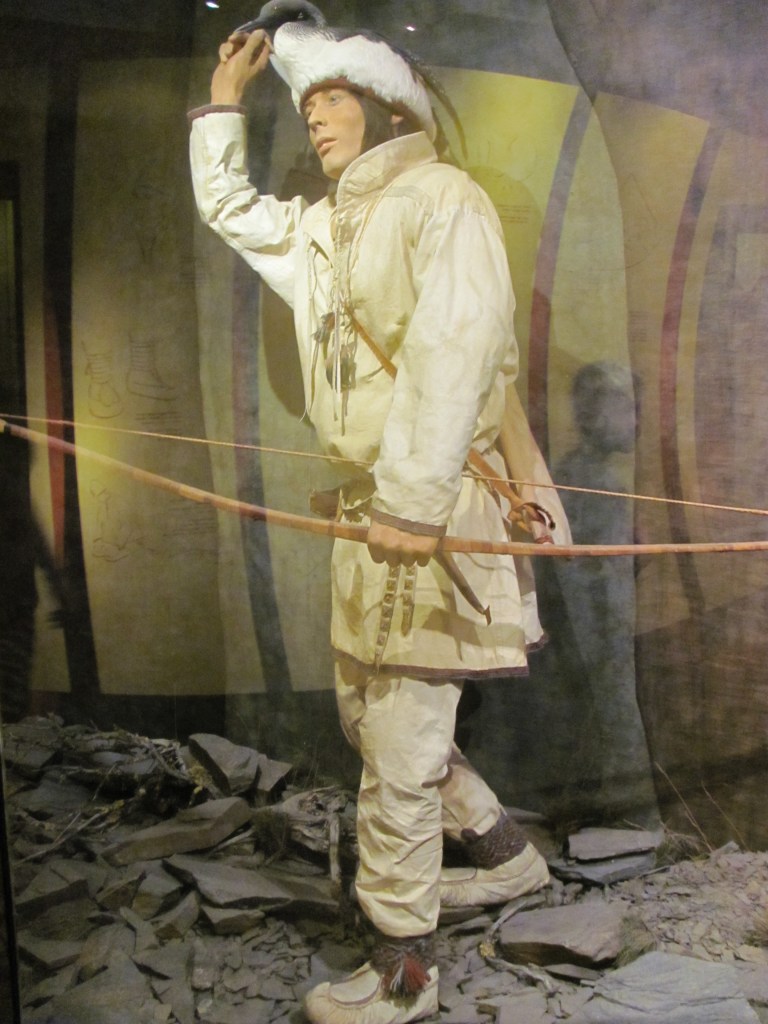

It is. Well fed, we spend the following couple of hours learning about the Sámi people and how they cope with a demanding environment.

“The Sámi are the only indigenous people in Europe”, a display board tells us. “They are thought to originate in the Upper Volga region in present-day Russia and to have spread along the Volga River to northern Scandinavia. The region they live is often called Lapland, but the Sámi themselves prefer to call it Sápmi. It stretches across Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia.”

Traditionally, the Sámi have lived by semi-nomadic reindeer herding, as well as fishing and hunting.

“It says here that reindeer husbandry is legally protected as an exclusive Sámi livelihood”, says the First Mate. “Only persons of Sámi descent with a linkage to a reindeer herding family can own, and hence make a living off, reindeer.”

In the last room we come to, panels describe the status of Sámi in Sweden. Historically, they were considered to be backward and primitive, and in the 1800s were subjected to forced assimilation with the rest of Sweden, with compulsory education and pressure to convert to Christianity. The Sámi language was even forbidden in schools. Coupled with Swedish settlers being encouraged to move north, and mining of oil, gas and precious metals, traditional Sámi reindeer grazing grounds and culture were under threat. Compensation was promised by the government for Chernobyl radioactivity in their grazing lands, but was never given.

“They seem to have had a bit of a raw deal”, says the First Mate.

Now there is some effort to redress these wrongs. A Swedish Sámi Parliament was established in 1993, and in 2021, the Church of Sweden apologised formally to the Sámi population for its role in forced conversions.

“It reminds me of the discussions that we had with Peter and Joanne about the Maori in New Zealand”, says the First Mate on the way home. “It’s a tricky one – to try and fully integrate indigenous people into western culture and its benefits, or to let them remain in their original state and a more sustainable way of life.”

“Perhaps both cultures can learn from each other”, I say. “Without being dominated by one or the other.”