There is a strong south-westerly wind blowing as we try and edge our way into Lochboisdale marina in the late afternoon. We have just arrived from Barra and are looking forward to a relaxing cup of tea and afternoon snack. Fortunately there are a few other boats there already, and the owners kindly help us to tie up. Even so, the wind blows us sideways and we end up on the opposite side of the finger pontoon from where we intended. Luckily there is no other boat there, and some strategic manoeuvring with the lines gets us where we want to be.

In the morning, we decide to take the community bus down to Eriskay to make up for bypassing it in the boat. We need to ring the bus company and request that they come to the marina, which they are happy to do. The other passengers turn out to be an eclectic mix of locals going shopping or visiting relatives in the next village, tourists from the ferry, and backpackers with bulging rucksacks. We seem to be the only sailors. We all manage to cram in somehow, even though the First Mate’s elbow keeps digging me in the ribs at every bump we go over. I make a note to get her some elbow pads for her next birthday.

We pass through several small crofting villages. I am not quite sure if village is quite the right description – individual crofts seem to be dotted more or less at random over the landscape reminiscent of Scandinavia, and names given to places where there seem to be a slightly higher concentration of houses. Baile is the Gaelic translation, so perhaps that is a better word to use.

In a little while, we cross the causeway linking South Uist to Eriskay. This was built in 2000, and is part of a scheme to link all of the Outer Hebrides with an integrated transport system of roads and ferries. It is now possible to drive all the way from South Uist, through Benbecula and North Uist, to Bernaray in the Sound Of Harris. Ferries complete the rest. It has all helped to rejuvenate the economy of the islands.

The bus drops us off just opposite the community centre in Eriskay. The next bus comes in two hours’ time and the one after that in four hours, so we have the choice of how long to stay. We are both feeling peckish, so we start off by walking down to the Am Politician pub near the beach for something to eat. The pub is named after the ship that sank in the Sound of Eriskay during WW2 with 336,000 bottles of whisky on board. Needless to say, this didn’t displease the islanders one little bit, and for the following few weeks they did all they could to retrieve as many of the bottles as they could. The problem was that no duty had been paid on them, and consequently the Customs and Excise weren’t too happy. They succeeded in catching some of the men red-handed and eventually tried them and gave them jail sentences, but they soon realised the futility of this, particularly as some of the local police were also involved in the ‘rescue’ and were reluctant to do anything about their fellow-islanders. Eventually, the customs people had the remains of the ship blown up so that no more bottles could be retrieved. The whole story is the basis of a book by Compton MacKenzie and an Ealing comedy film, both called Whisky Galore.

We sit outside and eat our soup and bread. A cool breeze begins to blow off the sea, but we decide to stay and enjoy the view. Just in front of us is a white sandy beach, which is where Bonnie Prince Charlie was supposed to have landed at the start of his ill-fated attempt to become the King of Scotland. We joke that he probably chose that beach as being the one that is most like the beaches in France when he arrived from, and would make him feel most at home.

We walk through the machair at the end of the beach and up onto the road over to the other side of the island. Machair is a natural grassland that is unique to the west coast of Scotland and parts of Northern Ireland, and is high in calcium from seashells that have been brought ashore by waves and then broken up.

On the way we pass a house with a magnificent view out over the Atlantic. It looks idyllic, but we wonder what it is like in the winter or during an Atlantic storm – it must cost a lot to heat, with all that glass. It doesn’t have a turret, so the First Mate is not so keen on it.

Below us we see the little harbour, consisting of just a pier and a stone breakwater, where the ferry from Barra comes into. In the distance, we can see the wake of a powerboat in the Sound of Barra, which we surmise might be the ferry on its way. A few cars are starting to pass us on the road on their way down to the harbour.

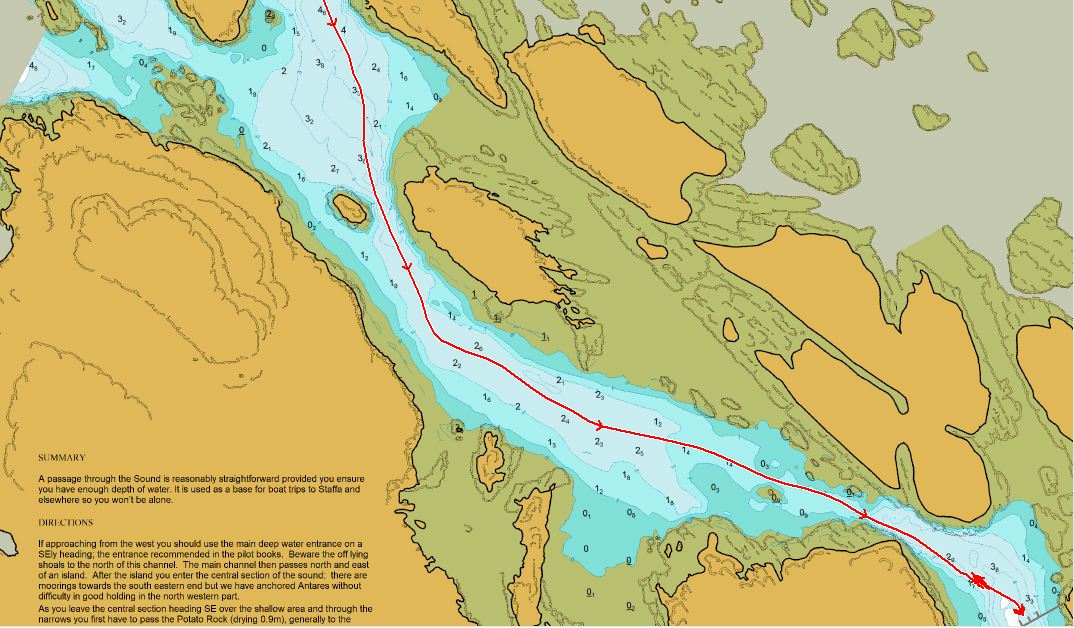

Eventually, we come to the little anchorage on the other side of the island that we had seen on the way up from Barra, called Acairseid Mohr. There are a couple of fishing boats tied up to the pontoons. In the middle of the harbour are two visitors’ moorings which we could have tied up to if we had come in. A few isolated houses dot the hillside around it. In the brilliant sunshine, it is an idyllic little spot, and we wish that we had taken the opportunity to have stayed there a night. But at least we are seeing it now.

We make our way back to the baille and sit in the sun outside the Eriskay shop and have an ice-cream while we wait for the bus back to Lochboisdale. A girl with an eastern European accent comes out of the shop with a cup of tea and sits in the shade. An old man with a white beard, belt and braces sits next to her. They laugh and talk. She is travelling around the Outer Hebrides by herself and had slept in her tent on the beach last night. She wants to see some sea-eagles. The old man shows her on a map where the best place to see them is, quite a long walk from here. She finishes her tea and sets off in that direction, rucksack on her back.

“Brave girl, travelling alone, and telling everyone where she is going”, says the First Mate.

The next day we decide to take the bus up to the Kildonan Heritage Centre, north of Lochboisdale on the road to Benbecula.

The man blinks back tears from his eyes as he watches the woman’s body being lowered into the recently dug pit. They had had only a short time together and now she had gone. He thinks back to the time they had met on one of his father’s trading journeys to the Kingdom of Fortriu, bringing fish from the coast in exchange for farm produce from the plains of the east. There had been laughter in her eyes then as he had given her fish to try, and she had spat it out, hating the strange taste. They had married and she had returned with him to Dal Riata. She had settled in, learning the language of his people, bearing his children, keeping house for him, grinding the grain for bread, and using her skills with the animals, but she had never felt completely at home.

The past winter had been cold, colder than anyone in the village could remember, even the old ones. At first the woman had been the stronger one – finding what little wood remained for the warmth-giving fire, then transporting peat from the men had cut it and left it to dry. Then she had started coughing, a deep hacking cough that had kept him and the children awake during the night. He had burnt more peat in the hearth to try and warm the house for her, but the smoke had seemed to make things worse. Then she had stopped eating, just lying there on their bed, her brown eyes looking at him with sadness. Then, in the night, she had called him and had asked him to take care of the children as she was going on a long journey. She didn’t know when she would see them again. In the morning she had gone.

He steps forward and puts the white pebble in her cold hands. She had always liked that pebble, the one that she had brought with her from Fortriu and kept ever since, saying that it reminded her of home. He watched as the other men place the stone slab over her tomb and cover it with cobbles from further down the beach. As they do so, a white-tailed eagle appears, swooping low over the small group of mourners before turning out to sea. It has come to take her soul away, he thinks. At least, if the Irish missionaries were right, she had gone to heaven where she would be looked after. And he would see her again when it was his turn.

“Shall we go and have lunch now?”

The dulcet tones of the First Mate bring me abruptly back to the present. I am looking at the remains of a woman whose grave had been recently discovered near Kilphedder, a few miles away from the Heritage Centre, and trying to imagine the circumstances of her death. The archaeologists have worked out that she had died in about 700 AD and was buried in a square grave, unusual in that area, that she wasn’t from the area, that she had arthritis, that her teeth were worn, and that she didn’t eat seafood. What kind of woman she had been, I wonder? How did she see the world? Did she have a family? What had been her loves and hates? We’ll probably never know, but it doesn’t do any harm to imagine. After all, she had been a living person once. I wonder if my bones will be on display in 1300 years’ time. Would people then be asking the same questions about me?

Just across from the Heritage Centre is the site where Flora MacDonald, the woman who helped Bonnie Prince Charlie, was supposed to have been born. I decide to walk over to the monument there. A farm track leads from the main road down past some farm buildings to a small knoll where the remains of a stone house lie, in the middle of which is the cairn announcing that the famous lady was born nearby.

I am so engrossed in reading the plaque, that I don’t notice that a bull and his harem have appeared from somewhere and cut off my escape route. The bull looks a mean one, judging from the narrowing of his eyes when he spots me coming down from the monument. I rack my brains trying to remember whether you should not make eye contact with bulls or whether you should try and stare them down, so rather than risk making the wrong choice, I scuttle back to the monument and shut the gate behind me. The bull paws the ground and some of the cows come up to investigate. I soon realise that I can’t stay here forever, and decide to try and make a run to a stone fence several metres away, and make my way along it on the other side. By this time, however, the cows are all around the monument and looking at me suspiciously, but I make it through them and clamber over the fence. The bull snorts. I crouch down and crawl my way along the fence, hoping I am out of sight, until I reach the farm track further up. I look back at the bull and punch the air in triumph. He is grazing and not even looking at me.

“You took a while”, says the First Mate back at the Heritage Centre.

“I nearly got gored by a bull”, I explain. “I was lucky to escape with my life.”

“Did you? Do you want to finish off this pot of tea? I don’t want any more”, she says. Somehow I feel that she is not taking her near-widowhood seriously enough.