“Yes, I am from Kristiansund”, says Lars. “Born and bred. It’s not the most exciting city, but it’s pleasant enough. Apparently it is where the first Norwegians are supposed to have lived, at least according to the archaeological evidence. It was first named Christiansund after the Danish-Norwegian King Christian VI in 1742, but the name was changed in 1877 to Kristianssund, then to its present spelling of Kristiansund in 1889. People often confuse it with Kristiansand in southern Norway, so we usually refer to it as Kristiansund N to indicate it is the northern one. We are heading back there now.”

Lars is the skipper of the boat tied up next to us at Håholmen. We are chatting to him as he gets ready to leave.

“We are still debating whether to get there by the outer route or to go round the island of Averøya”, I say.

“Both are fine”, he says. “But if you go around Averøya, you’ll go under the ‘Atlantic Road’, the road that connects many of the islands between Bud and Kristiansund. We are very proud of it. Some people think that it is a work of art – its sweeping arches and graceful curves are supposed to complement the natural landscape. It’s worth seeing.”

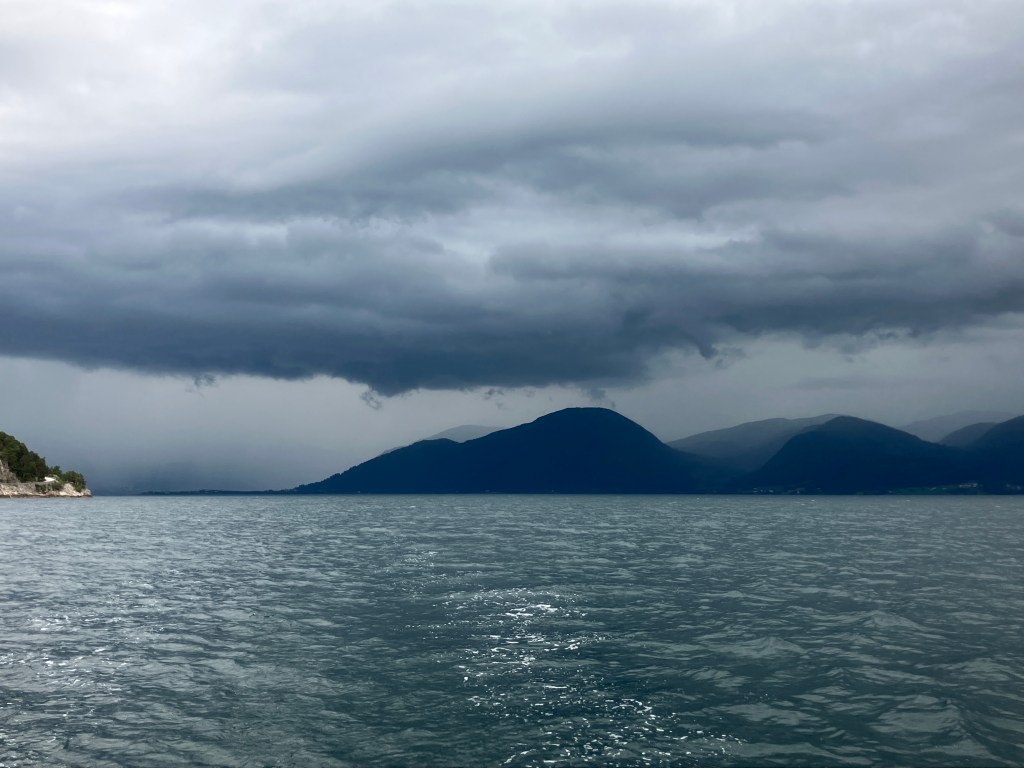

We leave a few hours after him, carefully following the perches marking the southern channel out of Håholmen. Soon we are at Storseisundet Bridge, the main bridge of the Atlantic Road. There is a strong current against us which buffets us from side to side, but we slowly make it through into Kornstadfjorden.

There isn’t much wind, so we drift along at 2½ knots, Kornstadfjorden giving way to Kvernesfjorden, which in turn becomes Bremsnesfjorden. Soon the sun comes out, and we relax in its warmth.

Lars’ comment that the first Norwegians had lived around Kristiansund has intrigued me, and I think back to the book that I have just finished reading, Ancestral Journeys: The Peopling of Europe, by Jean Manco. In the case of Norway, the ice sheets had prevented anyone living there for thousands of years, but as the ice retreated around 12,000 years ago, two groups of hunter-gathering people had begun to move in – one group originating in south-east Asia and migrating along the northern extent of the ice across Russia, and the second migrating northwards from continental Europe through Denmark. Sure enough, they met in Norway roughly where Kristiansund is nowadays.

“I wonder if that means you can see a difference in their descendants in Kristiansund?”, asks the First Mate.

“It wasn’t really a clear cut border”, I say. “There was a lot of intermarriage, and of course people from both groups moved in both directions along the coast. But the ones in the north were the ancestors of the Saami people of today. In the south, it is more complicated, because the hunter-gatherers gave way to the Neolithic farmers around 3500 years ago bringing agriculture as they spread across Europe from the Near East, then later by the Indo-European peoples from Central Asia, who brought their language that became the basis of most of the European languages we hear today.”

“Fascinating stuff”, says the First Mate. “So immigration has been going on for a long time, hasn’t it? Look, there’s a sea eagle in that tree.”

The eagle lets us take a picture of her, then flaps off languidly.

We eventually reach the Kranaskjæret Gjestehavn in Kristiansund. Lars is already there. He comes to give us a hand tying up.

“So you made it then”, he says. “Welcome to Kristiansund, the ‘salted-fish capital’ of Norway. It’s famous for its klippfish – you should visit the Klippfish Museum if you get a chance. It’s just over there, across the harbour.”

The next morning we walk around to the Klippfisk Museum.

“Hi”, says the young man behind the desk. “Welcome to the Klippfisk Museum. Would you like to have a guided tour? It’s included in the price, and you also get a free bowl of bacalao to try afterwards.”

“It sounds like a good idea”, says the First Mate. “I always think that you learn a lot from these guided tours. You can ask questions if you don’t understand things. Especially when things are in Norwegian. Where do we meet the guide?”

“I’m your guide”, the young man says. “I’ll do my best. It’s just you two. My name is Arne, by the way.”

“Klippfisk is basically any white fish that is salted and then dried in the sun”, he tells us. “Traditionally, they were laid out on rocks, hence the name klippfisk. Klipp translates as ‘cliff’ in Norwegian. Most of the time the fish used is cod, but it can also be pollack, saithe, or ling. Once it is dried, it will keep for several years.”

“The technique was developed in Spain, and was introduced to Norway in the late 1600s by Dutch merchants”, he continues. “Later the Scots also got in on the act – indeed, this very building we are standing in was built by a William Gordon from Cullen in 1749. He settled here and became fabulously wealthy buying and selling klippfisk. When he died, he left his wife and daughter £42 million, an absolute fortune in those days.”

“And not too bad these days either”, says the First Mate. “I think I need a new fishing rod. I’ve only caught one fish on this trip!”

“Good luck with that!”, laughs Arne. “But we shouldn’t forget the workers. Most of the hard work of salting and drying the fish was done by women – there is a statue honouring one of the Klippfiskkjerringa, or fish women, in the harbour. You should look out for it.”

“Was klippfisk all eaten here in Norway, or was it exported?”, I ask.

“It was exported all over the world, but the main markets were, and still are, Portugal, Spain, Brazil and Philippines. They are Catholic countries, and fish was an acceptable substitute for meat during Lent. Ships used to take the klippfisk to the Iberian Peninsula on the way out and fill their holds with soil for ballast on the way back. It was then emptied to make room for the next load. They say that most of the soil in the Kristiansund cemetery is Spanish soil.”

“How do you cook it?”, asks the First Mate. “It looks too dry and hard to eat it as it is.”

“Absolutely”, says Arne. “You need to rehydrate it by soaking it in water for a couple of days, replacing the water two to three times a day. That softens it and makes it much less salty. The classic Norwegian dish is boiled klippfisk with creamed peas and potatoes topped with a light cream sauce. However, another dish is bacalao, developed in Portugal, which is made by frying onions, garlic, and peppers in olive oil, adding tomatoes, sliced potatoes, olives, seasoning it with bay leaves, chilli and pepper, then pouring it over layers of the fish and simmering it until it is flaky and the potatoes are done. That’s also very popular here in Norway.”

After the tour is over, we sit in the café and taste the small bowls of bacalao that he gives us.

“I read somewhere that the Portuguese have developed it much more since then”, says the First Mate in between spoonfuls. “By adding lots more ingredients, such as eggs, cream, or chickpeas, and either grilling, frying, or baking it, and using different spices, such as coriander or parsley. So much so that they are said to have 365 different varieties – one for every day of the year!”

In the afternoon, we decide to walk up to the Varden viewpoint overlooking the city. On the way, we pass a impressive looking modern building.

“It looks like a block of flats”, I say. “I wonder who lives there?”

“It’s supposed to be a church”, says the First Mate, consulting the guide book. “Built in 1964 after its predecessor was destroyed by bombing in WW2. The most modern and daring one in the whole of Norway. Apparently it is worth having a look inside.”

“The theme is called ‘Rock Crystals in Roses’”, she whispers, once we are inside. “There are 320 coloured glass windows, and when the light strikes them, there is a burst of colours. The dark blue ones at the bottom represent man’s sinfulness, while the red, orange and white ones as you go up represent the process of enlightenment.”

Whether you believe the symbolism or not, it is certainly impressive. The ceiling beams and the side columns all contribute to the airiness and focusing of one’s attention on the chancel at the front.

We eventually reach the lookout tower at the top of the hill. Entry is free. A woman opens the door at the bottom for us.

“It was originally built as a watch tower to see ships coming to Kristiansund during the Napoleonic Wars”, she tells us. “Later it was the base station for an optical telegraph between Kristiansund and Trondheim. Be careful not to slip on the stairs. They are quite steep.”

The view from the top out over the city is magnificent. The walls between the arched windows are painted to give a panorama.

In the morning, we walk down to the waterfront to catch the Gripruta, the ferry across to the island of Grip.

“It’s definitely worth seeing”, Andy had told us. “But there is no room in the tiny harbour for a sailing boat to tie up. You are best to take the ferry across.”

We had tried to book places on it yesterday, but the sea had been too rough and the ferry service had been cancelled. Today, however, it is running.

The trip takes about forty minutes each way. We are surprised by the number of people boarding, and surmise that some of them must be ones like ourselves who would have gone the day before but couldn’t. When we arrive at island, we are organised by a young woman who was on the ferry, whom we had thought was one of the passengers.

“My name is Hanna”, she tells us. “I am your guide today. My grandmother used to live on the island, and I can remember visiting her here when I was a child. So I have a personal connection with it. Nowadays it doesn’t have a permanent population, but most of the cottages are owned by former residents or their descendants.”

“The island has been an important fishing community since around 900 AD. It became quite wealthy through exporting fish during Hanseatic times, and although the population did fluctuate due to the vagaries of fishing it probably always had a permanent population of around 200-300 people. But this could swell to 2000 people during the summer when fishermen would base themselves here rather that Kristiansund to be closer to where the fish were. However, the population eventually dwindled, and the last permanent residents left in 1974.”

“How did the island get its name?”, someone asks.

“Good question”, answers Hanna. “No-one really knows for sure, but one theory is that it came from the Old Norse word Gripar, meaning ‘to catch’, possibly referring to the fishing activities.”

“Does anyone own it?”, asks another person.

“Well, the first owner was the Archbishop of Norway”, she answers. “But in the 1500s, the King Christian III of Denmark seized it along with much other property of the Catholic church. It remained crown property until it was bought by a merchant called Hans Horneman in the early 1700s. Unfortunately this also gave him the fishing rights round about, and the fishermen had to sell him their catches at prices that he determined. They were more-or-less his vassals. These days it is owned and administered by the local municipality. Now if you just walk this way, we can see the church.”

“The church was built around 1470 AD on the highest part of the island, an impressive 10 m above sea level”, she continues. “The idea was that any violent storm wouldn’t reach it. It seems to have worked – there have been some very severe storms over the years, often destroying several houses, but the church has remained standing.”

The church is one of the stave churches that we had become familiar with by now, with the added distinction of being one of the youngest of such churches in Norway. At the front is the altar and a triptych.

“The story is that the triptych was made in the Netherlands, but was given by a Princess Isabella of Austria”, Hanna tells us. “She was only 14, but was on her way to marry the King, accompanied by the Archbishop of Norway. The ship she was on encountered a severe storm and nearly sank. However, it did survive, which Isabella put down to the Archbishop being on board, so she gave the paintings to the Norwegian Church by way of thanks.”

We move on to the power station and fire station of the island.

“The island’s electricity comes from two diesel generators that run from 0700 in the morning to 2300 at night”, she tells us. “And the fire station has the world’s smallest fire engine.”

“And over there is the Old Schoolhouse”, she continues. “Inside, you can still see the platform where the schoolteacher would stand. Nowadays, the building has been converted into a bar and café, and you can post letters there. Coffee, tea and snacks are also available.”

“It’s certainly all very picturesque”, says the First Mate as we carry our cups of coffee out and sit in the warm sunshine. “But I am not sure that I would like to have been brought up here. It’s a bit too cut off from the rest of the world.”

“If you had been brought up here, you wouldn’t have known anything else”, I say. “You’d probably be quite happy.”