“There’s another boat coming in”, calls the First Mate, as she ties us to the wooden quay. “I think it’s the one that was following us all the way up the fjord.”

We are in the small hamlet of Flørli near the head of Lysefjord, the first of the five large fjords of Norway. Yesterday, we had set sail from Tananger and had anchored overnight in a small bay called Vikavagen just inside the fjord entrance, and carried on up this morning.

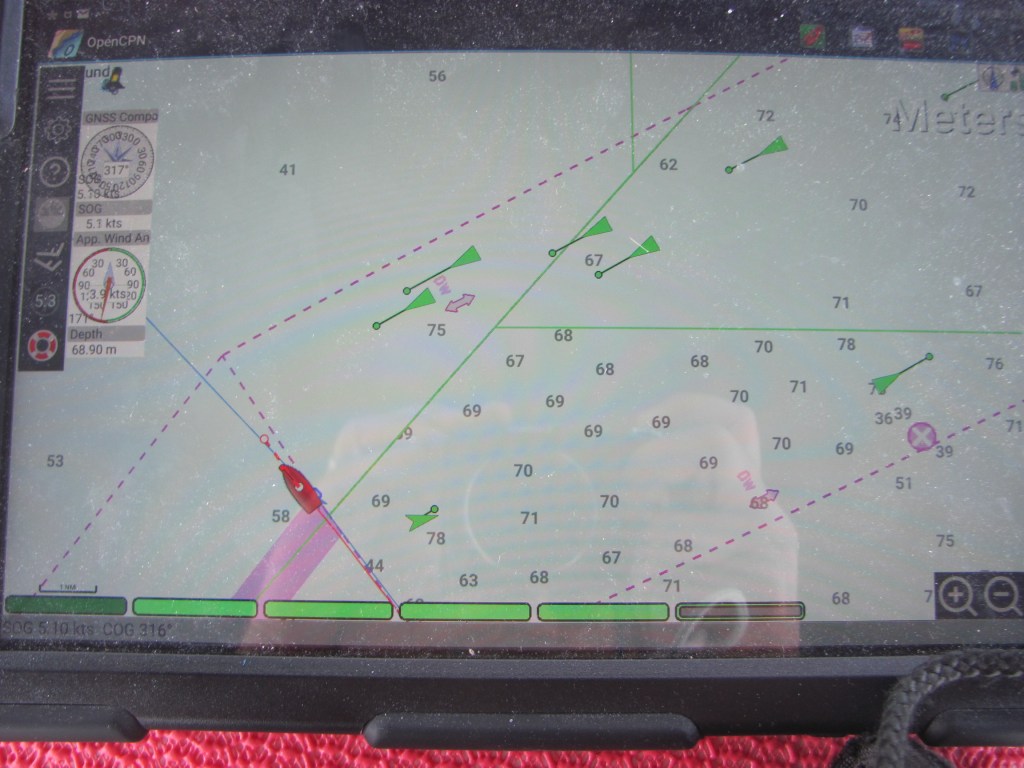

We had spotted the incoming boat first on the AIS, and since then we had kept an eye on it with the binoculars. As it approaches the quay, we see that is flying a French flag and that there are four young lads on it.

“One of them has a console in his hands”, says the First Mate. “Is he really playing games while the others are tying up?”

“I think it is a drone”, I say. “He’s probably videoing themselves coming in to the quay.”

Sure enough, we soon hear the high-pitched sound of a drone overhead. It hovers behind the boats tied up.

“I am taking a photo of you”, the drone pilot calls out. ”I’ll give you a copy. Smile!”

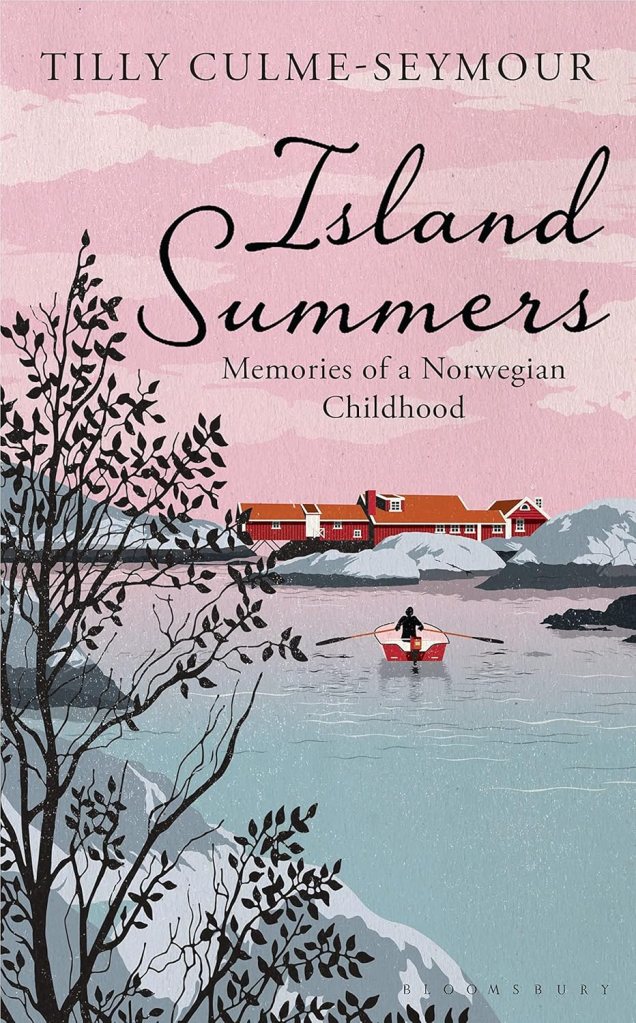

“We are all students on our gap year”, Drone Pilot tells us later as he transfers the photos to my phone by AirDrop. “We decided to do something different, so as we all like sailing, we bought the boat in August, spent a bit of time kitting her out, and set sail in October. We sailed down to Madeira, then across to the Caribbean, then back again. Then we sailed up to the Baltic, saw a bit of Sweden, and now we are doing Norway. After we get to Bergen, we want to sail across to Scotland before heading home again.”

There is an irrepressible enthusiasm in his voice that I find myself envying. What would I give to be young again, I think. Fit and strong, no aches and pains, no worries, no responsibilities, doing something exciting, and the whole of life stretching out in front.

“Come on”, says the First Mate. “You’ve done pretty well for yourself in terms of excitement.”

After a cup of tea, we visit the small museum in the old power station at the end of the quay.

It was built in 1918, we learn, to bring water from the mountain lake Flørvatnet 740 m above sea-level through a penstock to the power station and its generators. At first, it was hoped that the power would be used by a steelworks, but the steel market collapsed globally and the steel company went bankrupt. Eventually the power station ended up supplying electricity to Stavanger city, until 1999 when a new power station was built inside the mountain. Now this one is derelict.

“Did you read about the small railway line they constructed when they were building it?”, asks the First Mate. “Apparently one of the trolleys got away on them and started careering down the mountain with nine people on board. Luckily they all managed to throw themselves off and the trolley kept on going and sank in the fjord.”

“They also built a set of wooden steps so that the workers could walk up”, I say. “Apparently one pair of brothers used to carry packs of up to 135 kg of materials on their backs up these steps. Quite a feat. Nowadays, the wooden stairway has been restored and you can climb to the top. There are 4,444 steps, the longest wooden staircase in the world. Shall we do it?”

“I don’t think my knee is up to it”, says the First Mate. “And it’s just been raining. The steps are too slippery.”

When we get back to the boat, we discover that the wash from the high-speed passenger ferry has caused her to pitch up and down violently, and the anchor locker lid has been damaged by the anchor hitting the quay.

“It happens all the time”, says Tom, our German neighbour. “You need to make sure you are not tied too closely to the quay. You can use another rope to pull the boat closer when you want to get on and off.”

“Why can’t the ferry just slow down, so there is not so much wash?”, says the First Mate, irritated. “Now we’ll have to repair it.”

We set off the next morning back down the fjord. There’s no wind, but the sun is shining, and it looks stunning.

On the way, we pass the famous Preikestolen, a slab of rock shaped like a church pulpit jutting out from the cliff, 600 m up. Already we can see people on top having their photographs taken near the edge. We hadn’t been able to see it on the way up because of the low cloud and mist.

In the evening, we reach Finnesandbukta on the island of Mosterøy, and tie up next to a wooden ship. It has a plate with the name Restauration on its stern.

“It’s a replica of the ship that sailed from Stavanger to New York in 1825, two hundred years ago, carrying immigrants to America, mostly Quakers”, our neighbour tells us. “It has become sort of an icon of Norwegian immigrants to America. They are planning to repeat the voyage in two weeks’ time, leaving on July 4th. Of course, this one makes use of all the modern navigational equipment.”

“I hope that their visas and everything are in order”, I say. “You hear of people having all sorts of trouble at the US border these days.”

“Funny you should say that”, he answers, smiling. “The original ship contravened American law by having too many immigrants on board for its size, so the company was fined, the ship confiscated, and the captain arrested when they arrived. But when President John Quincy Adams heard about it, he rescinded all of these. The immigrants were allowed to settle and became known as ‘sloopers’.”

After lunch, we borrow some bicycles from the nearby hotel and cycle up to Utstein Kloster, a medieval monastery. Originally a royal estate during Viking times, the monastery was established in the 1200s. After the Reformation in 1537, it was turned into a bailiff’s residence, and is now a museum and concert venue. It is the only monastery that has been preserved in Norway.

I sit in the courtyard and pretend I am a monk. The bees are buzzing in the flower garden, the birds are singing in the trees nearby, there is the smell of soup and freshly baked bread coming from the refectory. I think that I would quite like it.

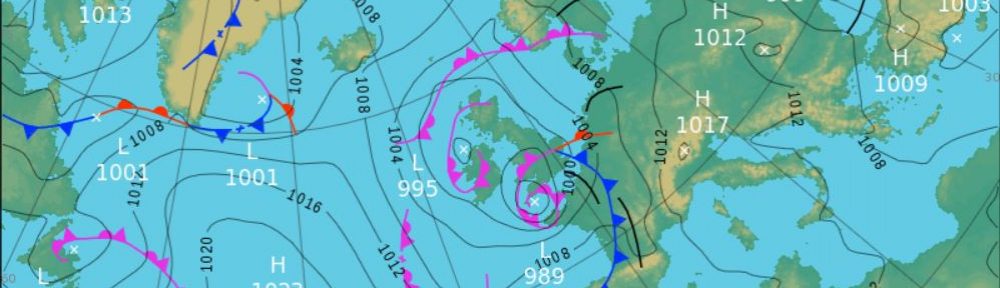

We set sail the next morning, heading for Haugesund. Soon we are in the Karmsund Strait, the official start of the ancient North Way trading route from which Norway derives its name. To our left is the island of Karmøy, and to the right the Norwegian mainland. The wind is just enough off head-on for us to sail close-hauled, albeit slowly. Just as we pass the rather industrial-looking town of Kopervik with its massive aluminium smelting works, there is a ping on the First Mate’s phone.

“We’re right behind you”, the message says.

We turn around. It is Simon and Louise, whom we hadn’t seen since the foraging session in Smögen.

“We had planned to stay the night in Kopevik”, they tell us later. “But we found it so depressing there that we decided to carry straight on to Haugesund. Then imagine our surprise when we saw Ruby Tuesday on our AIS just in front of us!”

They motor on slowly to Haugesund. We decide to continue by sail as we are enjoying the sunny weather and don’t feel we are in a hurry. They arrive a bit before us.

“The harbour is completely full because of the midsummer revelries”, Simon radios us. “There is half a place next to us, but it has an iron girder sticking up out of the water, so there is a risk that you might hit it, especially if there is a strong wind.”

It doesn’t sound very appealing. The First Mate does a quick scan on her phone of other possibilities to tie up. It seems that there is a community pontoon on the nearby island of Vibrandsøy. We motor slowly over to it. It is full with small motor boats. No room for us.

“Let’s tie up against these tyres, and review the situation”, I say. “I am sure no-one will mind.”

Two elderly gentlemen approach. We eye them warily, expecting them to tell us that we can’t tie up here. But we needn’t have worried.

“As far as we are concerned, it’s fine to stay there”, one says. “But there are strong winds forecast for tomorrow, and it is a bit exposed there. There is a better place against the white boatshed around the corner. If you like, we’ll meet you around there and help you tie up.”

We motor around the corner. It is right next to the community pontoon. The two men appear, grab our ropes, and attach them to rings embedded in the concrete at each end of the shed. But our euphoria at having a place to stay overnight turns to dismay when we realise that there is no way off the boat as the boathouse doors are blocking our exit.

The two men look perplexed.

“We’ll try and make room for you on the community pontoon”, one says.

They push and pull the motorboats around until there is enough space for Ruby Tuesday on one side. We tie up. This time we can step off easily.

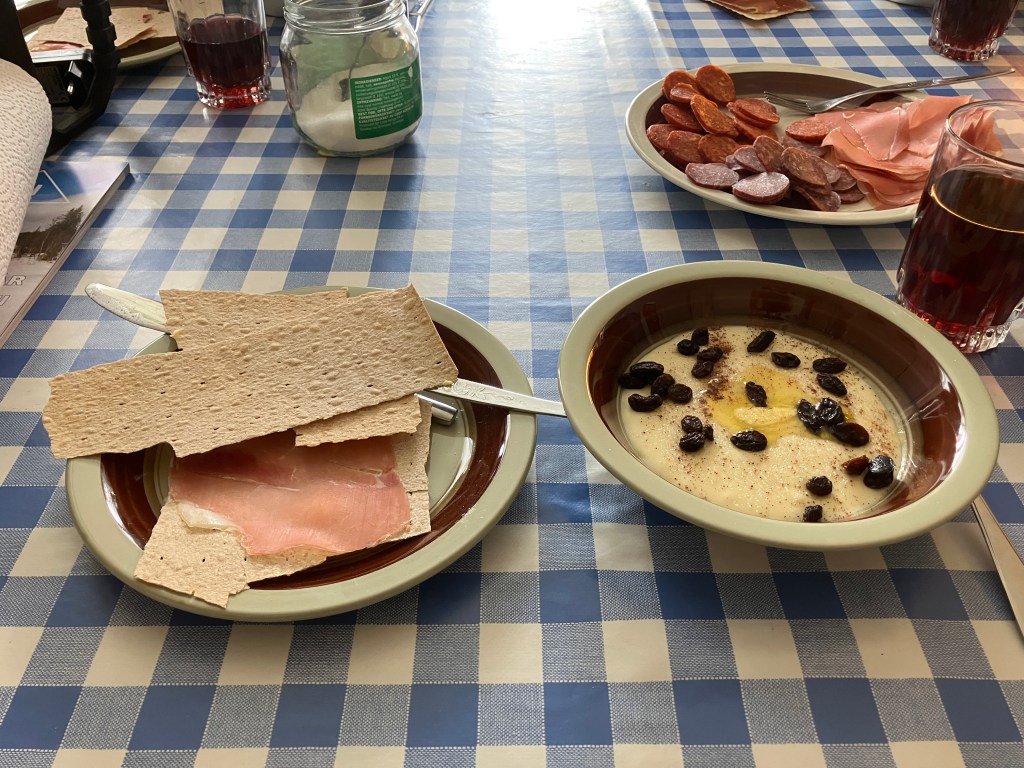

“You can stay here as long as you like”, they say. “By the way, we are having a small midsummer get-together which you are welcome to join if you like.”

It’s very kind of them. We have our dinner, and then clutching a bottle of wine, we amble over to the gathering of 30-40 people on the grassy area between the houses.

“We are a club dedicated to restoring and maintaining traditional wooden boats”, one of the men says. “By the way, my name is Svein. It’s a royal name from Viking times. I have been working on helping to restore that old ship over there. We are planning to sail it down to the Mediterranean when it is ready.”

He points to a wooden ship near the entrance to the harbour.

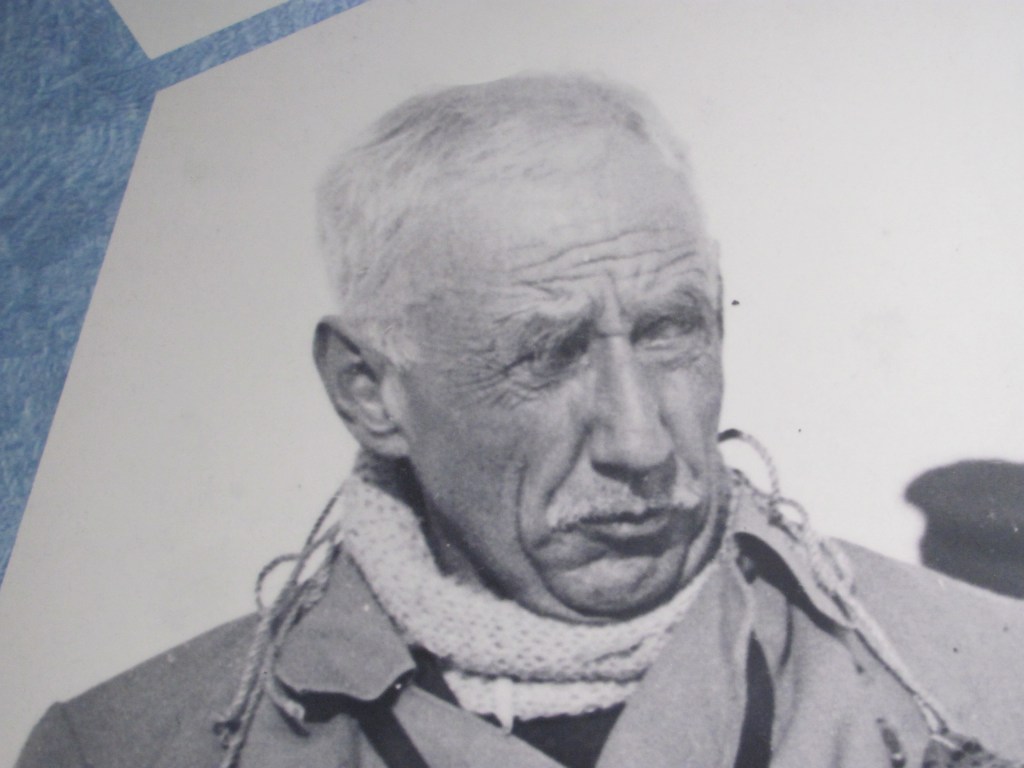

“You Norwegians have always been sea-adventurers”, I say. “From the Vikings themselves, to Nansen, and to Heyerdahl. Not to mention that boat being restored at Finnesandbukta. Apparently, they are sailing it to America in two weeks.”

“Ah, the Restauration”, says Svein. “Yes, I was helping with that as well. And there’s also a local lad who keeps on trying to get to Greenland from here, but he’s tried four times now and has had to turn back each time for various reasons.”

“You must mean Eric Anderaa”, I say in surprise. “I follow him from time to time on YouTube. He must be away on one of his voyages at the moment?”

“No, he is still here”, responds Svein. “His boat is over in the main harbour. I think he might have given up on Greenland. This year he is sailing to Edinburgh. I am not sure when.”

The next day, the midsummer celebrations are finished, and everyone has gone home. The main harbour is almost empty. We move Ruby Tuesday over to be closer to the city centre.

In the afternoon we take the 209 bus that takes us a few miles south from Haugesund to the small town of Avaldsnes, from where we walk the 1 km or so to the Norwegian Historical Centre and St Olav’s Church perched on a hill overlooking the Karmsund. We had seen the church from the boat as we had passed.

“You’re just in time”, says an enthusiastic girl dressed as a Viking. “The next tour starts soon. Quick, the introductory film is just about to start.”

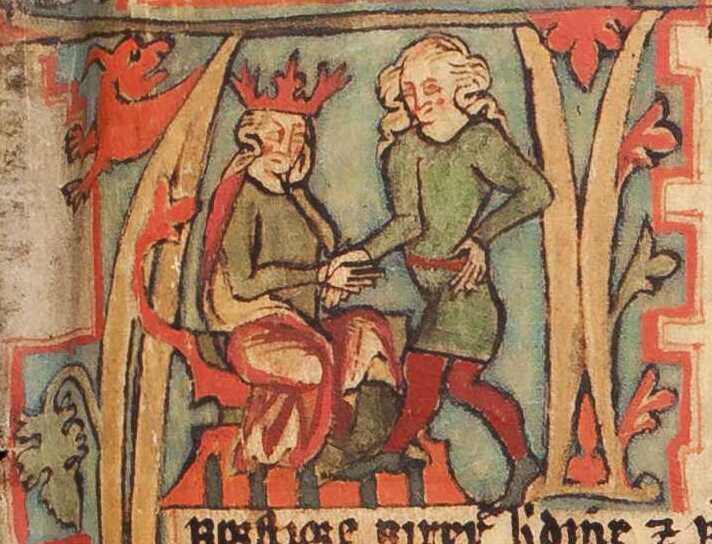

We take a seat in the front row. The film describes the rise of the sækonungr, the sea-kings, in the mid-700s – a coastal elite who did not own much land because of the inheritance system of the established manors and estates on the fertile inland areas passing only to the eldest sons. Instead, these sækonungr lived by using the infertile coastal islands to control maritime traffic, especially the trade in furs, down, walrus ivory, and whetstones from the Arctic. They gradually became wealthy in their own right, concentrating political power to themselves.

“Avaldsnes was named after one of these early sækonungr called Augvald”, the film tells us. “He had his seat of power here because the Karmsund narrows made it easy to control and tax ships passing through.”

“Later, another of these sækonungr was buried in the Great Mound here in AD 779. We don’t know for sure who it was, but it was possibly either Hjorleif the Woman-Lover or his son Half Hjorleifson. Not long after that the Viking raids on Western Europe began – the first raid on Lindisfarne monastery in the UK was in AD 793.”

The film ends, and we explore the museum. We learn of Harald Fairhair who won the Battle of Hafrsfjord in AD 872 against his main adversaries and in so doing unified the whole of Norway under one ruler. He chose Avaldsnes as his seat of power.

“I read that Harald Fairhair is a big deal for Norwegians, as he gave them justification and a sense of identity when they became independent”, I say. “It’s their foundation story.”

Unfortunately, it seems that modern scholarship has cast doubt on whether he even existed. Most of what we think we know about him comes from the Icelandic Sagas, which are not known to be terribly accurate in the details.

“Look, it says on this panel that the church outside is generally thought to have been built by Olaf Tryggvason, who forcibly converted people to Christianity by the sword and became Olaf I of Norway”, says the First Mate. “Perhaps not surprisingly, he wasn’t well liked, and was eventually killed in a battle orchestrated by his third wife and King Svein Forkbeard of Denmark.”

“Marvellous names”, I think. “But if you live by the sword, you die by the sword.”

We decide to have a coffee at the cafeteria, and go and sit on a grassy mound outside. A sign tells us that it is the Cellar Mound. It seems that Augvald, the original king that gave his name to Avaldsnes, worshipped a favourite cow that gave him good luck in battle, so the two were buried in adjacent mounds when they died. The story goes that when Olaf Tryggvason opened the mounds, sure enough he found human bones in one, and cow bones in the other.

“It certainly makes a good story”, says the First Mate.