“You can leave your car with a friend of mine”, says Ingemar, over a beer. “He has a big barn, so it will be under cover.”

We had met Ingemar on the Danish island of Christiansø last year, and had sailed along with him to Limhamn marina on the outskirts of Malmö, where he was also storing his boat over the winter. Limhamn was where he had been born and grown up, so despite now living in the south of France, he knew the place and its people well.

“It’s better than leaving it at the marina, where it is likely to get covered in salt spray from the wind”, he continues. “I always leave my motorhome with him.”

He has a large motorhome that he uses to travel around in when he is not sailing. We had been most impressed with it – it is fitted with state-of-the-art gear, and even has a small garage in the back of it in which he keeps his SmartCar for travelling around locally in when he reaches his destination.

The next day, I follow him to his friend’s place and park our car in the barn. His motorhome is already there. Several other cars are also in the barn, some classic, some covered in dustsheets. Our car will have others to talk to.

“Your car will be fine here”, says Ingemar’s friend. “I won’t move it from its place. Remember to disconnect your battery so that it doesn’t go flat.”

On the way back to the marina in his SmartCar, Ingemar talks about the local history of the area.

“Limhamn actually means Lime Harbour. There was a huge quarry, the Limhamns Kalkbrott, from which they used to extract limestone and take it by train to the harbour where it was converted into cement. I can remember as a young boy being woken every morning by the huge explosions as they blasted out the limestone. Our whole house shook. The cement was shipped all over the world – the ‘Christ the Redeemer’ statue in Rio de Janeiro was actually made using Limhamn cement.”

“Do they still make it here?”, I ask.

“Not any more”, he says. “Nowadays, most of Sweden’s cement is made on Gotland. They have turned the quarry here into a nature reserve with a lake in the middle which attracts wildfowl and other animals. Apparently the nature reserve has one of the very few populations of the European green toad left in Sweden. Look, the observation point is just off here. I’ll take you to see it.”

We stand on the edge of a giant crater and look down at the small lake and regenerating vegetation. On three of the sides of the rim are new-build housing areas, and on the fourth is the motorway to the Øresund Bridge.

All that material removed from the earth and used to make the cement to construct the hallmarks of modern civilisation, I think.

“Ironically, they have to keep pumping water out of it so that the whole area doesn’t become a lake”, says Ingemar. “It makes you wonder how sustainable it will be in the long run.”

—-

We set sail the next morning. We are a little nervous, not only because this is our first sail of the season, but also because it is the first proper test of everything on the boat after the winter repairs – particularly the engine which had had the heat exchanger removed. Will it all function, or did I forget to reassemble some vital bolt or screw, I wonder.

But everything works as it should, and we are soon sailing merrily northwards along the Øresund. It is just as well, as we had arranged to meet three other boats by a specific date in the small village of Smögen some 200 miles away well up the west coast of Sweden, and we already don’t have much time to get there. But at least we are finally on our way.

“Look, there’s Kronborg Castle over there”, says the First Mate, pointing to an impressive looking structure on the Danish side. “The town nearby is Helsingør, where we used to catch the ferry across to Sweden the times we drove to Stockholm.”

We cross the shipping lane at right angles to reach the Danish coast. Now the wind is on the nose, and we have to furl the sails and start the engine. Eventually we reach our destination for the night, the small town of Gilleleje on the north coast of the island of Sjælland.

“It looks like we’ll be here for a few days”, I say, perusing the weather charts and forecasts in the evening. “Strong north winds and lumpy seas are forecast for the next three days at least. We can’t sail into those.”

“Well, I am sure we can find enough things to do here for a few days”, says the First Mate. “It seems a nice little place. I read that there’s a good fish shop here with fresh fish from the fishing boats.”

In the morning, I walk over to the shower block for my customary shower, taking with me the card we were given to access and pay for the toilets and showers.

“I am not sure how much money is left on the card”, the First Mate says. “I had rather a long shower last night, and I may have used quite a bit of it. But there is definitely some left.”

Outside a group of people are busy doing aerobics, led by an athletic hunk in his twenties.

“Legs up and twist”, he chants. “Arms straight in front, and bend. One, two, three four.”

Inside, I undress and wave the card in front of the reader. The shower starts. I stand underneath it and soap myself up. After one minute there is a click, and the water stops. I wave the card again in front of the reader. Nothing. There is a beep and a message appears on the reader display.

“Insufficient funds on this card to continue.”

Consternation! Dripping soapsuds and shampoo, I have no way of rinsing them off. The machine for topping up the card is at the yacht club, 100 metres away. And I can’t put my clothes on top of wet suds anyway.

The brilliant idea occurs to me that the only way is to rinse myself off at one of the basins in the common washroom. But what if someone comes in? I have to take the risk.

Starkers, I stand on my towel and slosh myself with water from the sink. The aerobics chanting outside ends, and there is the sound of the outer door opening. I just manage to wrap my towel around myself before the washroom door opens.

I avert my eyes from the curious gazes of the Athletic Hunk and several other sweating faces.

“Shower not working”, I mumble, pretending to be a foreigner not used to Danish bathroom technology. No one looks convinced.

The Athletic Hunk waves his card in front of the reader. The shower spurts out water perfectly. I pretend not to notice, dress, and beat a hasty retreat.

“I have a bone to pick with you”, I say to the First Mate when I get back to the boat.

“I told you there might not be much on it”, she says unsympathetically. “You should have topped it up before you went in.”

In the afternoon, we visit the Gilleleje museum, the central focus of which is the evacuation of Danish Jews to Sweden in October 1943. Two of the museum staff are sitting outside the café in the sunshine drinking coffee.

“The Jews in Denmark were left relatively alone for the first part of the war”, one of them tells us. “Mainly because Denmark had an official policy of cooperation with the Germans. But in October 1943, this arrangement broke down, and the Germans began arresting Danish Jews.”

“Suddenly, Jews from all over Denmark started coming to Gillerleje”, the second one tells us. “It’s the closest point to neutral Sweden, and they were trying to flee to there. Many came by train to the station here. You can find out more about it in the exhibition over there.”

“Local people hid the fleeing Jews in their lofts”, one of the panels tells us. “Then when a boat became available, they would be taken down to the harbour in the dark of night and put aboard the boat. Children were even sedated and carried down in cardboard boxes so they wouldn’t cry out and arouse the suspicions of any chance German patrols. The boat would then take them across to Sweden.”

Some of the refugees weren’t so lucky. Someone informed the Germans that there were Jews hidden in the loft of the church – a patrol was dispatched there, the Jews were arrested and taken to the nearby Horserød prison camp, and from there to Theresienstadt concentration camp in present-day Czechia, where many of them died.

“Look, here’s one of the boats that transported people across”, says the First Mate, pointing to a dinghy in the middle of the exhibition. “It’s so small. I wouldn’t have liked to be on the sea in one of those in the middle of the night.”

“You probably wouldn’t mind if the alternative was being taken to a concentration camp”, I say.

Later, we walk out to the outskirts of the town to see the memorial of the Jewish evacuation and of those who died.

Teka Basofar Gadol, it says in Hebrew. “Let the Great Ram’s Horn proclaim our liberation.”

—-

“Well, I have to say, this is the type of sailing I like best”, says the First Mate, stretching out languidly in the warm sunlight bathing the cockpit. “A nice light breeze to keep us moving, no heeling, and no waves to make us roll from side to side. Bliss.”

We are on our way from Læsø to Marstrand in Sweden. The winds had changed, and we had been able to sail from Gilleleje to the island of Anholt and from there to the island of Læsø. We had originally planned to explore both islands in detail, but a quick scan of the weather forecast had convinced us that if we were ever to get to Smögen to meet the others, we had to press on. The next three days were to be strong winds from the north again, which would confine us to port. We weren’t too keen to do that. Today was to be light winds and smooth seas all the way to Marstand, so much so, I was expecting that we would probably have to motor some or most of the way. We promised ourselves that we would visit Anholt and Læsø on the way back and do them justice.

The First Mate is right though – it is pleasant. Except is doesn’t last long. After about half an hour, as I had expected, the wind drops to three knots and the sails flap listlessly. Shortly we are drifting along as less than two knots. At this rate, we might be lucky to get to Marstand by the morning. But at least the sun is shining.

I go downstairs to make a cup of tea. While I am down there, the boat suddenly lurches and begins to heel. Out of nowhere, the wind has picked up. I glance at the instruments – 18 knots! Where has that come from? I try to carry my cup of tea up the companion way without spilling it; by the time I get there, the wind is touching 25 knots and we are speeding along at 7½ knots.

“I thought it was supposed to be calm all the way”, shouts the First Mate. “We need to reef. We’re heeling far too much.”

We put in two reefs just to be on the safe side. The boat stabilises, but she is still hurtling along at almost undiminished speed.

Driven by the wind, the waves slowly begin to grow. Unfortunately, they are an our beam, coming from the side, and Ruby Tuesday rolls as each one travels underneath us.

“I’m feeling a bit squeezy”, says the First Mate, starting to look green. “I think I’ll go below.”

“Queasy”, I say. “You mean queasy.”

“Whatever”, she says, disappearing.

Ruby Tuesday settles into an uneasy rhythm – rolling precipitously with each successive wave, but somehow managing a consistent seven knots. Clouds roll in and the sun disappears, adding to the melancholy. From time to time, the bow plunges into a wave, sending green water cascading over the foredeck and windows of the spray hood.

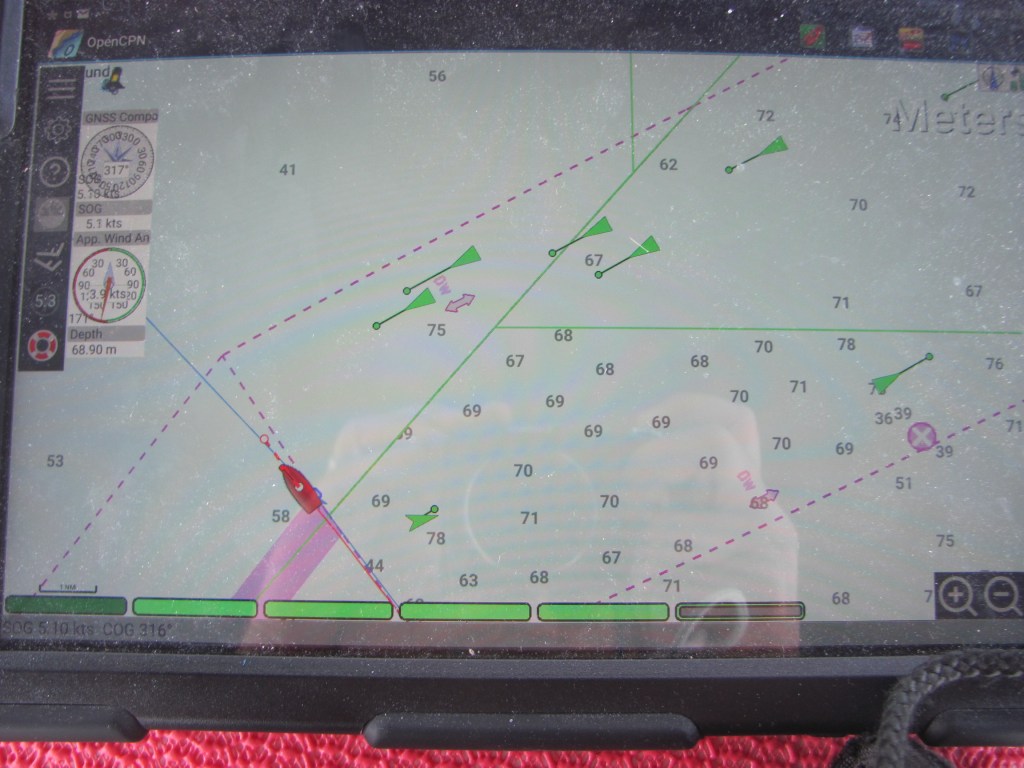

A ship appears out of the haze. We are crossing a shipping lane and I have been keeping a watchful eye out for ships to avoid. The AIS tells me that our closest point of approach to this one is 75 m. That’s a bit too close. I adjust the autopilot two degrees to the south.

“Ruby Tuesday, Ruby Tuesday”, suddenly crackles an Indian voice on the VHF. “Your course is very close to ours. We’re closing fast.”

“Ship calling Ruby Tuesday”, I respond. “I am aiming to go behind you.”

I adjust the autopilot a further two degrees to the south just to be on the safe side. A few minutes later we pass behind the giant cargo ship, and I am watching its stern disappear slowly into the haze again. The AIS tells me she is bound for Baltimore.

The hours pass. There is no let up in the windspeed and the waves are as high as ever. But we are making progress, uncomfortable as it is, and gradually Sweden comes into view. Eventually we reach the entrance to the fjord where Marstrand, our destination, is located. Like the flick of a switch, the wind suddenly drops and the waves calm down, and we sail sedately up the fjord with only the genoa up as we pass the imposing Carlsten Fortress on the hill guarding the entrance to the town.

“Well, I am glad that is over”, says the First Mate. “I didn’t enjoy that at all. It was odd wasn’t it? When we set out it was calm, and here it is calm. Did we just imagine all those strong winds and waves in between?”

A good question.