“Oh, no”, says the First Mate, peering through the binoculars. “”There’s someone else already there. I was hoping that we would have it all to ourselves.”

We had set sail from Smögen that morning. The other ‘foragers’ had already dispersed – Hekla had already left for Norway across the Skagerrak as they had to be in Bergen within a week to meet their daughter, Aloucia had decided to have a couple of days on Väderöarna (the Weather Islands) before doing the same, and Amalia was heading for Strömstad for a change of crew. We are meandering our way northwards so that we can visit our friends Ståle & Gunvor north of Oslo. On the way, we had seen a small bay that looked ideal for anchoring overnight.

“Never mind”, I say. “We can anchor a bit away from him and pretend he isn’t there. At least it isn’t packed with hordes of boats.”

We drop anchor in the middle of the small bay. It is idyllic. A steep cliff drops precipitously to the water on one side and lush green woodlands cover the gentler slopes on the other. Not a house, car, or even a telephone pole are to be seen. We could be the only people alive. Apart from the sole occupant of the other boat, of course.

We cook dinner and bask in the warmth of the last sun of the day before turning in.

In the morning, I awake and lie watching the patterns of light dancing on the ceiling for a few moments. I make myself a cup of tea, and go out on deck. The other boat has already gone, and we are alone. A small gulp of cormorants fly overhead in formation, disappearing over the cliffs. Further down the bay, two swans come in to land, their feet swooshing across the surface before they settle down into the water, shaking their wings dry before folding them.

I pick up the book I am reading at the moment. It is the latest of John Gray’s, entitled The New Leviathans. Bleak but stimulating, he discusses the end of the liberal democracy era and its Enlightenment concepts of individualism, equality, universalism, and meliorism – the idea that things will always improve. Only 30 years ago, with the fall of the Soviet Union, the feeling in the West was that these ideas had triumphed over everything else, that liberal democracy was the pinnacle of human government, and that all that still needed to be done was to make every country believe that. Not so, says Gray – so many terrible things have happened since then, and the West and its freedoms are visibly crumbling with the rise of right-wing extremism, authoritarianism, and religious nationalism. The role of these new forms of government are more to protect citizens, or subgroups of citizens, rather than to protect basic freedoms. What’s more, he argues, all these -isms are just words with no substance; the reality is that it is just people going about making decisions for their daily lives. Such words, however, are dangerous as they make people do things in the name of ideologies.

“Breakfast time”, come the dulcet tones of the First Mate from down below. “I’ve put on the coffee. You can make the toast.”

I put down the book and go inside. Why am I reading this rather than enjoying the beautiful scenery around me, I ask myself. But I know I’ll continue reading it when the next chance comes.

After breakfast, we push on to the Koster Islands, about 12 miles west of Strömstad. We arrive at Ekenas, the main harbour. There is a strong current through the narrow channel in which the marina is located, and it is not easy to tie up. The neighbours help us, but somehow we still manage to nudge the pontoon and take a small chip out of Ruby Tuesday. I am not very happy.

“Come on”, says the First Mate, obviously seeing the look on my face. “Let’s go and get an ice-cream. That’ll cheer you up.”

Near the ice-cream shop is a wooden building labelled the Naturum. It’s a kind of museum, and free. An enthusiastic woman greets us at the door.

“Welcome to the Naturum”, she says. “I’m your guide. I am studying ecology at university. You can learn all about the natural history of the Koster Islands here. Did you know they’re perched on the edge of the Norwegian Trench?”

We have to admit that we hadn’t heard of the Norwegian Trench.

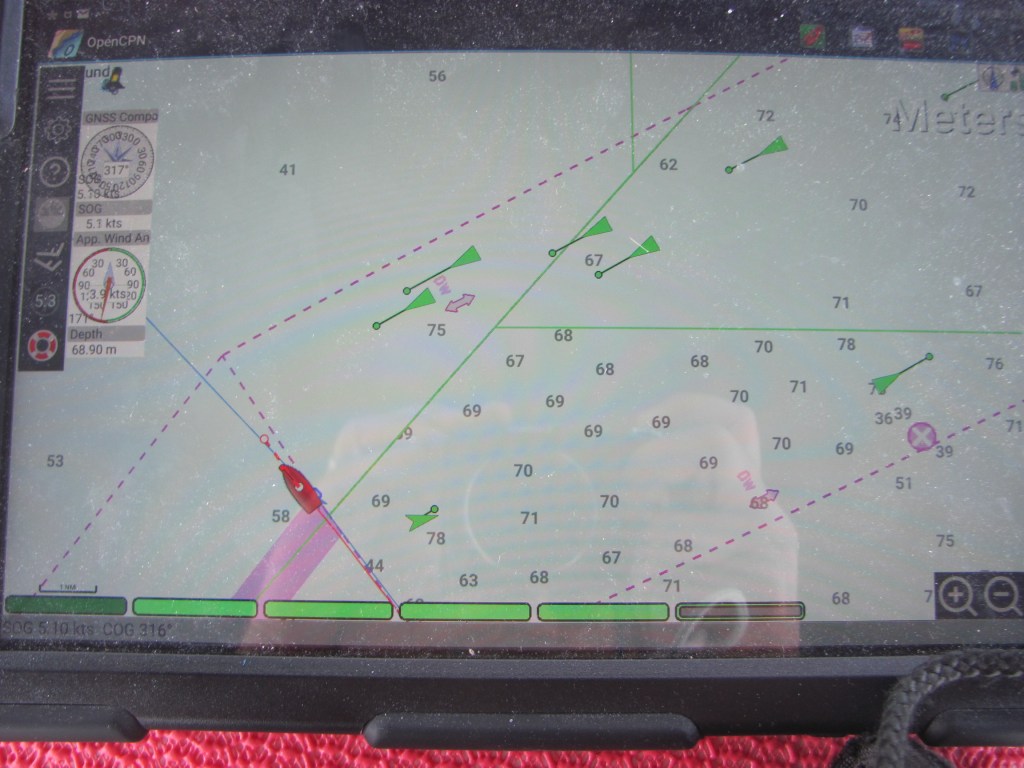

“It’s a deep trench that curves all the way around the south of Norway, up to the Oslofjord, then a bit down the west coast of Sweden just past the Koster Islands”, the Enthusiastic Ecologist explains, leading us to a scale model lit with pulsating lights. “It’s up to 700 m deep in places, and up to 95 kilometres wide. A current flows along it bringing water from the Baltic to join the Norwegian Coastal Current along the west coast of Norway. These pulsating lights show you the currents.”

We tell her that we are planning to sail across to Strömstad, and from there across to Risør in Norway.

“Well, you’ll be sailing over it both times”, she says. “In fact, the deepest part of it is actually just off Risør. Keep an eye on your sonar – the edge of it comes up very suddenly like a cliff, so you can’t really miss it.”

It’s fascinating stuff. I read that evening that the Norwegian Trench is unusual for oceanic trenches in that it has been created entirely by erosion and glacial processes about 1 million years ago rather than by tectonic plates moving over each other as most other ocean trenches are.

In the morning, we unload the bikes, and set off to explore the islands. We come to the grocery store in the centre of South Koster, which judging by the amount of people, seems to be some sort of communal meeting place.

“Let’s get lunch here”, says the First Mate. “I’m famished. I’ll go in and get something to eat and drink. You stay here and find a table and look after the bikes.”

She comes back out with some sandwiches and orange juice.

The bread in the sandwiches is dry and they taste old.

“The packet says they are best before June 30”, says the First Mate. “That’s a month away. They should be OK.”

I notice on the packet that they were made on May 2. Not only that, they were made in Italy!

“I can’t believe it”, she says. “Made in another country a month ago. No wonder they taste funny.”

“Don’t beat yourself up”, I say. “At least the orange juice tastes good.”

We eventually reach the village of Långegärde on the edge of the narrow channel that divides South Koster from North Koster. The electric ferry from the mainland has just arrived and is disgorging its passengers. We had seen it several times before when it stopped at Ekenas where we are tied up – with almost silent engines apart from a faint hum, it had seemed to creep up on us without warning and rock our boat violently with its wash. But all credit for being sustainable.

There is a small chain ferry that goes from one side of the channel to the other. We join the queue.

“The last ferry goes at 1630”, a woman in the queue tells us. “If you miss it, you can get the main passenger ferry back again, but it doesn’t go until 1900. You’ll have a bit of a wait.”

On the other side, we continue our cycle ride through beautiful green forests until we come to the small harbour of Vettnett. There isn’t a lot there apart from children fishing, but it is beautiful.

“We’d better get back”, says the First Mate. “I think we should try and catch the 1630 chain ferry. I don’t really want to wait around until 1900.”

We make it just in time, and are soon back on the South Koster side.

“You can actually work the chain ferry yourself”, the university student operating it tells us. “But you need to have been trained and to have a license. Lots of people who live on North Koster do just that and are not tied to timetables.”

On the way back to the boat, we stop and climb the path to the highest point on the Koster Islands, Valfjäll, rising to the awe-inspiring height of 50 m. But there is a good view of the archipelago from the top.

“I read that you can even see the Weather Islands from here”, says the First Mate, pointing southwards.

I strain my eyes, and just manage to see a slight smudge on the horizon. I clean my glasses to get a better view.

The Weather Islands seem to have disappeared.

In the morning, we sail over to Strömstad on the mainland. I keep an eye on the depth underneath us. Sure enough, as the Enthusiastic Ecologist said, it plummets suddenly from about 20 m near the harbour to more than 200 m as we cross the Norwegian Trench.

“I don’t like that very much”, says the First Mate. “All that water underneath me.”

“We learnt when we were kids that you can drown in a foot of water”, I say. “It hardly matters if it is 20 m or 200 m underneath us. Better instead to make sure that we don’t fall overboard.”

We have decided to leave Ruby Tuesday in Strömstad and take public transport to Oslo, have a couple of days there exploring the city, then carry on up to Gjørvik in the centre of the country where our friends, Ståle and Gunvor, live. We had considered sailing up the Oslofjord to Oslo, but had been advised by a number of people that while sailing up the fjord is not very difficult, sailing back again is, mainly because the predominant winds are from the south and we would be battling them all the way. As we still needed to make it to the west coast of Norway, a not inconsiderable distance, we decided this was good advice.

The First Mate finds an AirBnB in Oslo for a couple of nights, and books tickets on FlixBus.

“We need to get the local 111 bus out to the E6 motorway to catch the FlixBus”, she says. “There’s only 10 minutes between one and the other. Let’s hope the local bus is on time.”

It is, and soon we are whizzing along the E6 on our way to Oslo.

“The AirBnb is in Rosenhoff”, says the First Mate, when we arrive. “We need to catch a tram there. If we buy a 24 hour Oslo Pass, we can use it on all public transport to go exploring tomorrow as well. It also includes free entrance to museums and art galleries.”

In the morning, we take a ferry across to the Bygdøy peninsula where the Fram and Kon-Tiki museums are located.

The Fram was a purpose-built ship for polar exploration. Its hull was ingeniously designed in an eggshell shape so that the ice would force it upwards rather than crushing it, effectively ending up floating on the surface. The rudder and propeller could be retracted so that they wouldn’t be damaged by the ice. It was specially insulated and stocked so that the crew could live on it for up to five years.

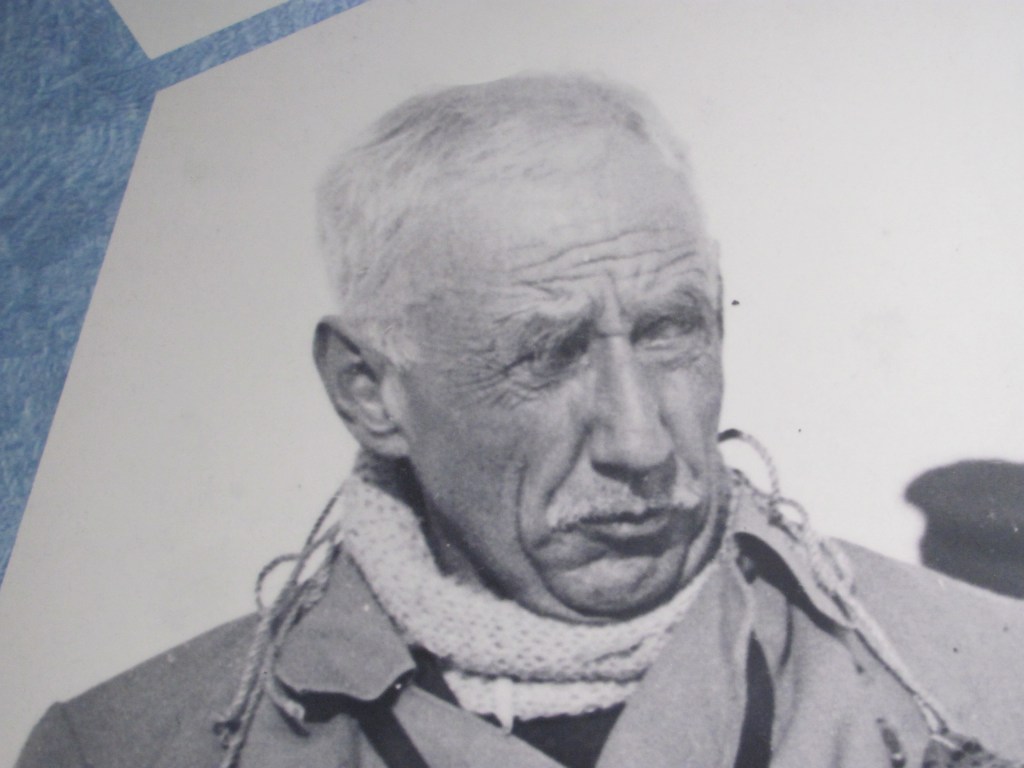

“The Fram was commissioned and used first by the Norwegian polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen in 1893”, a panel tells us. “It was used to test his theory that there was an east-west current across the north pole. By trapping the Fram in the ice around the Siberian islands, they found that it emerged into the North Atlantic Ocean after three years, partly proving the theory, although it didn’t cross the actual North Pole.”

“It was also amazing that the same boat was used by Roald Amundsen when he reached the South Pole in 1911”, says the First Mate over a coffee later. “He was originally planning to be the first to reach the North Pole, but was beaten there by the American explorer Robert Peary, so he secretly changed his mind to aim for the South Pole. He didn’t even tell his crew until the last minute of the change in plans.”

“And in doing so, he beat Scott’s British expedition there by five weeks”, I say. “I remember learning about it at school, as Scott had stopped in New Zealand on his way to stock up. Unfortunately, they all died on the way back. It’s the stuff of a heroic British legend, even though they failed. Now, drink up, and let’s go and see the Kon-Tiki museum. It’s just across the way.”

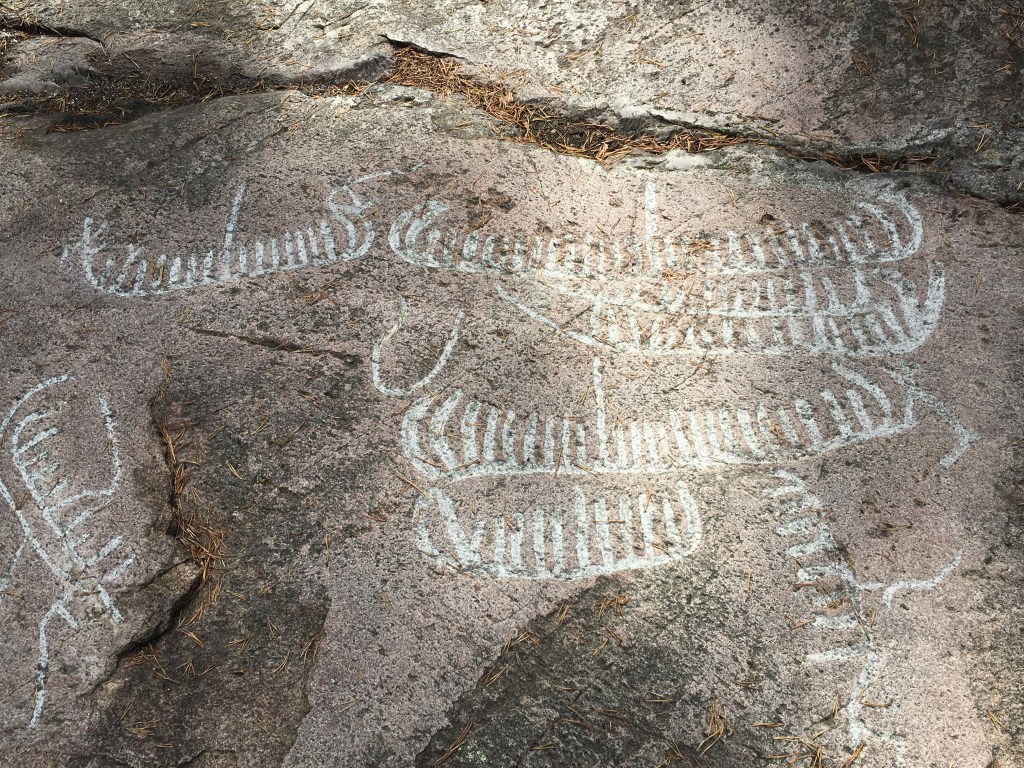

The Kon-Tiki is a raft built of balsa wood that was used by the Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl to test the theory that the inhabitants of the the Polynesian islands could have originated from people who travelled by boat from South America using the Humboldt Current to carry them. He built the Kon-Tiki in Peru in 1947, and by reaching the Polynesian islands of Tuomotu, showed that it was at least feasible.

“It’s a great story”, says the First Mate, “but did you read that genetic and language information collected since have all but proved his theory to be false, and that Polynesians have their origins in South East Asia. Most reputable anthropologists nowadays dismiss his theories completely.”

“It didn’t seem to deter him, though”, I say. “Another of his theories was that the Ancient Egyptians could have sailed across the Atlantic to trade with the inhabitants of the Americas. So he built another raft called the Ra out of papyrus. After one failure, he rebuilt it and managed to sail from Morocco to the Caribbean in 1970, again proving that it was at least possible. I remember keeping a scrapbook on it when I was at high-school.”

“He certainly had an adventurous life”, says the First Mate. “It’s a pity after all that that none of his ideas turned out to be right.”

“That’s how science works”, I say. “People come up with different ideas, put them to the test, consider all the evidence, and either discard, modify or adopt them. Unfortunately, Heyerdahl’s mostly ended up in the dustbin. But you never know what will happen in the future.”