“I think we should press on”, says the First Mate over breakfast. “Storm Floris is coming from the south-west in a couple of days, and we don’t want to be caught out. As nice as Molde is, it is rather exposed to the southwest and there’s not much protection in the harbour.”

She has a point. Storm Floris is approaching the UK and gusts of up to 90 miles per hour are being talked about. It’s only a matter of time before it reaches Norway. We really don’t want to be sailing in that.

“We can get to Bud today”, I say. “And then try and get around the Hustadvika before it comes. We could then shelter in the tiny island of Håholmen. Alternatively, we could stay in Bud itself – I’ve heard that it is quite well-protected.”

The Hustadvika is another of the officially designated ‘exposed or dangerous areas’ in Norway, and consists of a cluster of rocks, skerries, and small islands open to the vagaries of the Atlantic Ocean. Like the Statt and Godø, a benign weather window needs to be found to traverse it safely. Storm Floris doesn’t sound like it would be one of those.

We set off. Once we are round the Julneset point and into Julsundet, we catch the wind from the southwest, and have an exhilarating sail past the islands of Otrøya and Gossa right up to Bud. We have had a month of glorious sunshine, and while we wouldn’t have wanted to see the fjords in any other way except that, it had meant that there was very little wind for sailing. It is great to be able to stretch our wings again.

When we arrive in Bud, there is another British boat tied up to the landing. It turns out to be a father and daughter.

“We’ve been up to the Lofoten Islands”, the daughter tell us. “Now we are on our way back again. We need to get the boat back to the west of Scotland where we keep it, but I have leave my Dad to do it on his own from Ålesund as I need to be back to work next week. I’m a vet.”

“I’m used to sailing by myself”, says the father, anticipating the question from the looks on our faces. “So it’s not a big deal, although I will miss her company. She’s a good sailor. But this Storm Floris coming is going to delay things a bit. I’d be sailing right into it.”

We spend the next day exploring Bud. It’s a small picturesque fishing village with a supermarket, café, church, and museum. It’s claim to fame is that it was where the last independent Norwegian Privy Council met to vote in 1533 to secede from the Kalmar Union with Denmark and Sweden, and to become an independent country and reject the adoption of Lutheranism as the national religion. Unfortunately that didn’t end well, and Norway ended up in being a province of Denmark for nearly 300 years.

“It’s amazing to think that if they had succeeded in seceding, Norway would still be a Catholic country today”, says the First Mate. “And not Lutheran like the other Scandinavian countries.”

We come to the coastal walk north of village. The sun is shining, there’s no wind, and it’s hot. We climb one of the rock outcrops and look out over the Hustadvika, the route we will be taking northwards.

“It’s so calm and peaceful now”, says the First Mate, wiping her brow. “It’s hard to believe that a violent storm is on its way.”

In a sense, we could have set off this morning, but we had heard from some other sailors we are in touch with that our intended destination, Håholmen, is low-lying and quite exposed, so we had decided that discretion is the better part of valour, and that we would sit out the storm in Bud instead.

The peace and quiet is suddenly shattered by a frenzied cacophony of seagull cries up ahead. Several seem to be harrying another large bird, swooping and diving at it from all angles.

“It’s a sea-eagle”, I say. “They are warning it to stay away. Perhaps it lives near here, out on the skerries.”

We end up on top of the small hill overlooking the town where German troops built gun emplacements as part of a series of fortifications called the Atlantic Wall to resist an Allied invasion. As it turned out it was never used in action, and may have even contributed to Germany’s defeat by diverting troops for its operation away from mainland Europe.

The storm is forecast to reach us sometime in the night. We have been keenly following the havoc that it is causing in Scotland, knowing that we would be in for something similar. Already there are some preliminary strong gusts. I double up on the mooring ropes just in case one breaks or works itself loose.

“I’ll put some rubber snubbers on as well”, I say. “That’ll stop sudden jerks stressing out the ropes. You can batten down the hatches.”

“I don’t think we have got any battens”, says the First Mate.

“I didn’t mean it literally”, I say. “I just meant to make sure all the windows and skylights are shut. It’s nautical-speak.”

As predicted, Storm Floris hits us in the early morning. I am awoken by the sound of the halyards whipping against the mast and the boat listing alarmingly to port as the winds howl over the harbour breakwater and catch the top of the mast. Luckily the breakwater protects the hull from the worst of the force, although from time to time, plumes of spray come hurtling over it, drenching the boat and joining the rivulets of rain already coursing down the canopy tent.

We eat breakfast huddled in the cabin, listening to the wind whistling through the rigging. Outside we see a seagull struggling to fly against the wind, making no progress at all, giving up, and going with the flow. I check the windspeed to find that it is up to 42 knots. That’s a Force 9 gale. And that’s in the harbour – what is it like out at sea?

In the afternoon, I notice that I have forgotten to take down the courtesy flags and that they are starting to work their way loose. When there is a lull, I clamber out onto the fore-deck and manage to retrieve two of them, but the Scottish one has somehow managed to get itself stuck on the port spreader. Without climbing up, there is nothing I can do except pray that it will somehow hang on.

It doesn’t. Two hours later it is gone. I have a quick scan around the harbour on the off-chance that it might still be floating on the water or have blown onto a jetty, but nothing.

After two days of incessant lashing, the storm dies down. We consult the BarentsWatch website and calculate that the sea should have calmed down enough the next morning for us to attempt the Hustadvika. We have decided to do the inner passage through the rocks and skerries, the so-called Stoplane route, which although requiring greater care in navigating our way through narrow gaps, is more protected from the Atlantic swell.

We awake early and cast off. There is still some residual swell left over from the storm, but it is not rough. We wend our way through the twisting route, making sure that we approach each marker pole on the correct side. Jagged rocks pass only metres away from our hull. We eventually reach the narrowest part, between the two Stoplane islands that give their name to the passage, where the marked channel is only two boat-widths wide.

Eira looks at the boat approaching. It is the same one that she had seen a few days earlier on her visit to Romsdalfjord, and again when the seagulls had harassed her.

I know who you are, she thinks. I have seen you before. But you are in my world now. Your kind may have driven us out from the land you have colonised in Romsdal, but this is our domain. Yet still your minds are set on bending nature to your will, of claiming the seas as your own. You say that we have no right to your livestock, why then do you assume you have rights to our fish? Have you forgotten that once there was enough for all; now your numbers and your machines take almost everything and leave little for the rest of us? But we are all part of nature, you are not set to rule over us. If you can’t or won’t learn that, the Doom will return; but this time it will be for us both.

“Look, there are two sea-eagles on that pole”, exclaims the First Mate, pointing to one of the markers. “One’s just flown off.”

“They are beautiful creatures”, I say, trying to take a photo at the same time as I attempt to manoeuvre the boat through the narrow gap . “Especially when they fly. So big. I wonder what she is thinking about?”

“Deep philosophical thoughts, I am sure”, she answers.

Eventually we reach Håholmen and find a berth at the small harbour.

Several people are milling about as though they are waiting for something.

“The boat back to the mainland is coming soon”, explains a neighbour. “A lot of people come over for the day, have a walk around the island, something to eat and drink, then go back in the evening.”

“Unfortunately, the restaurant is fully booked for tonight”, the receptionist at the hotel tells us. “It’s very popular. You need to book well in advance. But there’s a couple of videos you might be interested in in the small museum at the back. One’s of the history of the island, and the other is of the things that the previous owner, Ragnar Thorseth, got up to. If you want to see them, let me know and I can switch them on for you.”

We decide to have a cup of tea and then see the videos. On the way back to the boat, we meet another British couple.

“We’re sailors too”, says the woman. “But our boat is in Greece. We’re on a car tour through Norway, as it is too hot to be in the Mediterranean at the moment. We’re staying at the hotel. The food here is great – we ate at the restaurant last night. But we have decided not to go tonight, so you could have our table if you like. I’ll talk to Reception.”

A stroke of luck! We had heard good reports of the restaurant, and had been keen to try it. Soon we are booked in for the 6pm sitting.

We find our way to the small museum at the back. The receptionist turns on the video projector.

“Håholmen was founded in the 1700s and soon become a hub for fishermen and traders”, the first film tells us. “Around 1900, it was purchased by a Bård Bergseth, who lived here with his family, and maintained the fishing industry. In the 1990s, it was taken over by his grandson, Ragnar Thorseth, who turned it into a hotel and conference centre.”

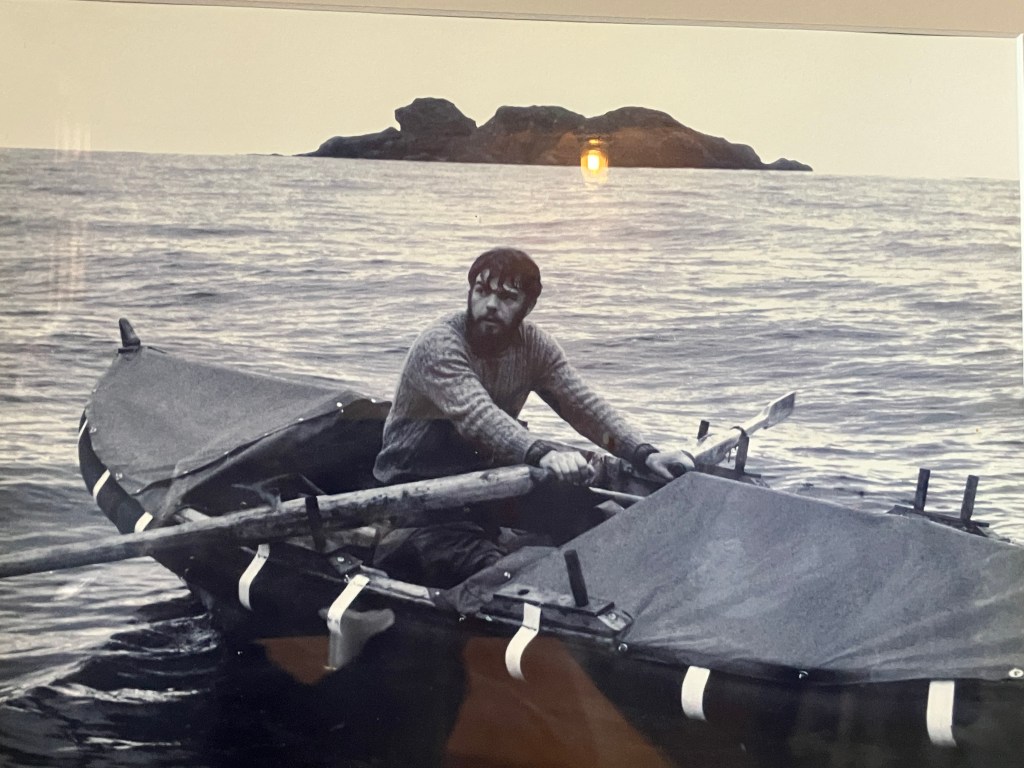

Ragnar Thorseth is a larger-than-life Norwegian adventurer, not all that dissimilar to his more well-known countryman, Thor Heyerdahl, we learn from the second film. In the 1960s, he had rowed single-handed from Norway to Shetland in an open rowing boat. Later, in the 1980s, he had built a replica Viking trading ship, the Saga Siglar, and had sailed around the world in her. He also managed to pack in a trip by boat through the Northwest Passage, an overland trip to the North Pole, and overwintering on Svalbard with his family. His exploits earned him the name of ‘The Last Viking’ in Norway.

“He still keeps coming to the island from time to time, even though it is now owned by Classic Norway Hotels”, the receptionist says as she comes to turn off the projector. “He lives on another island a bit further south from here. In fact he was here just a couple of weeks ago. In his Viking replica ship. He’s quite an amazing character.”

At 1800, we find ourselves at the restaurant. Knowing the history of the island, how could we have anything but fish? The First Mate goes for the monkfish; I decide to have the klippfish.

“Klippfish is a white fish, usually cod, that has been split, salted and then left to dry in the sun”, the waiter explains. “It is a traditional dish in this area. I can guarantee you will like it.”

He’s right. It’s delicious, with potatoes, minted green pea purée, cured pork belly bacon, and beurre blanc sauce, all rounded off with almond cake for dessert.

“I’m not sure that I am going to make it back to the boat”, says the First Mate. “I think I have eaten too much.”

“I’ll see if I can find a trolley”, I say.