“I’m getting a bit fed up with these storms”, says the First Mate. “It wasn’t that long ago since Storm Flores hit us.”

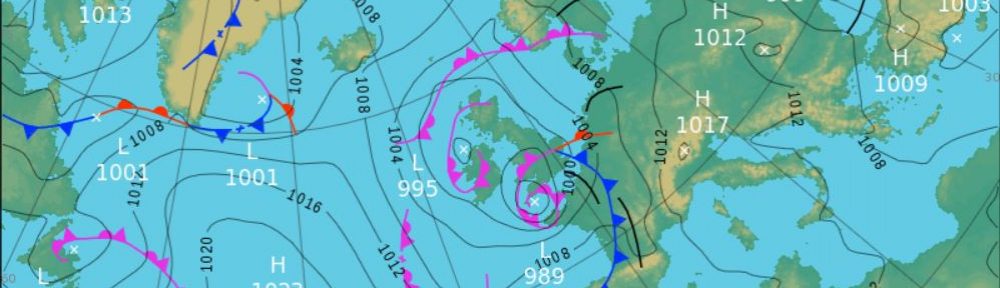

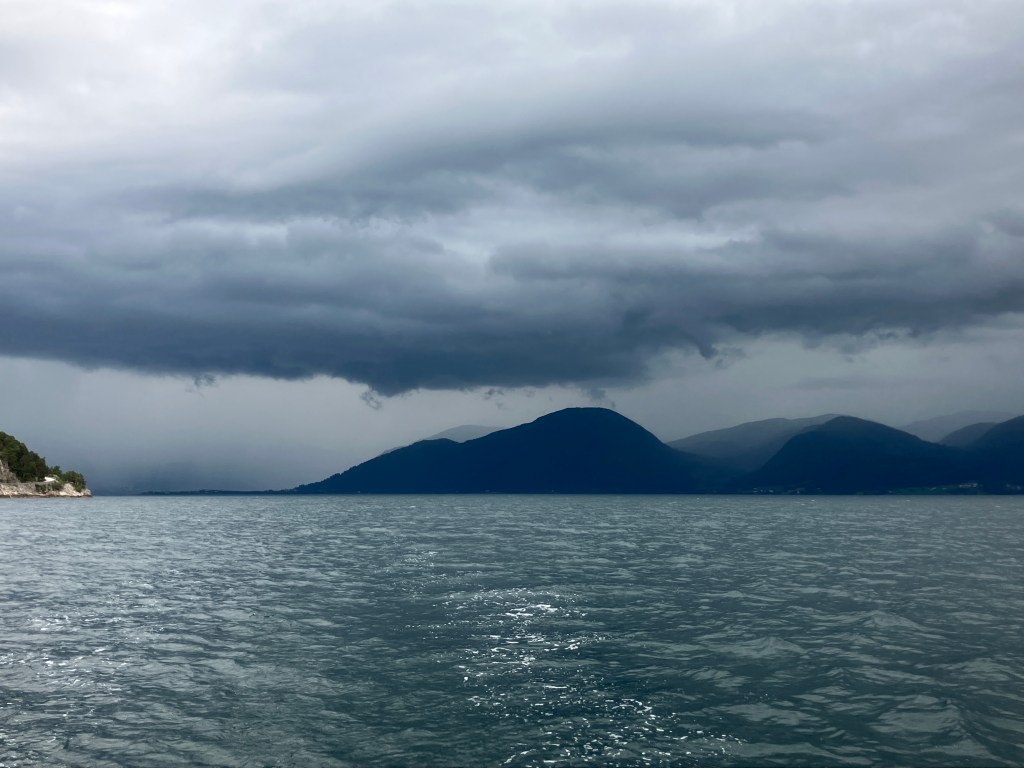

I feel the same. We are in the marina of Hellingsjøen sheltering from 50 knot winds from the west. We had known they were coming and had chosen Hellingsjøen as it had looked reasonably sheltered on the charts. And so it is, but the winds are still managing to come over the surrounding trees and across the small bay with considerable force.

“Just imagine what it must be like out in the open sea”, I say, by way of reassurance.

“Look, I think that the pontoon next to us is getting closer”, she responds, alarm in her voice. “The wind is blowing us towards it.”

It does seem to be. I clamber out, and, braving the gusts, gingerly make my way along our pontoon to the shore. Looking back, it is clear that the whole structure is being bent in a curve by the wind. If one of the retaining chains was to break, we would smash up against the boats on the neighbouring pontoon. Not a nice thought.

“Don’t worry”, says a passing fisherman. “We’ve had much bigger boats than yours tied up there. Nothing’s ever happened yet.”

Hardly reassuring. What if this blow is the one that breaks the camel’s back after being weakened previously? But there isn’t much we can do except keep a watchful eye on the situation and be ready for disaster if it happens.

Luckily it doesn’t. The wind keeps up for a day and a half, then dies down. We wake up to a bright and sunny day, a calm sea, the pontoon back where it should be, and a nagging irrational thought that perhaps we just dreamt it all.

We pack up, cast off, and continue on our way to Trondheim.

“The battery alarm is going again!”, calls the First Mate.

I’ve already heard it. Over the season we had noticed that there was a slow decline in the amount of time the batteries would last after a full charge. Even when sailing, we need them to power the autopilot, run the navigation instruments, charge the tablets, computers, and everything else that keeps us going. Previously they would last some days before we needed to plug into shore power and recharge them, but now it was down to a couple of hours.

We had charged them overnight at the small harbour of Hasselvika, but two hours later as we sail up Trondheimfjorden, they are almost flat again.

I am not really surprised. They have reached the end of their design life of eight years, so they are likely to give up soon anyway. I am just a bit surprised it has happened so quickly.

“Turn everything off”, I shout back to the First Mate. “We can make it without using the autopilot, and I think there is enough power in the laptop and tablet to navigate. We can see if we can find a solution when we get to Trondheim.”

Luckily the wind is directly from behind, so we use the genoa only. We still manage to make seven knots.

We eventually arrive in Trondheim. The First Mate has called ahead and has been informed by the harbourmaster that the main Skansen marina is full because of a large conference on aquaculture for the next few days, with many attendees coming in their own boats. We are best to try the Brattøra marina further along, he advised us. Even there, several berths are reserved, but we might find a spot.

Luckily there is one place left. As we tie up the occupants from a neighbouring boat come and help.

“We’re from the UK as well”, they tell us, noticing our flag. “But we are flying back home in a couple of days. We’re leaving the boat at the Stjørdal marina along the coast a bit. We are sailing up there tonight, packing everything up tomorrow, then catching our flight the next morning. The good thing about Stjørdal is that it is close to the airport. We’re Chris and Terry, but the way.”

We invite them in for a cup of tea and cake.

“You’ll find Trondheim interesting”, says Chris, dropping cake crumbs on the floor. The First Mate looks aghast, but doesn’t say anything. “It was the capital of Norway during Viking times, and used to be called Nidaros after the River Nidelva which runs through it. Later it was called Trondheim after the Trønder people who lived in the area. The cathedral is still called Nidaros Cathedral.”

“The cathedral is definitely worth a visit”, Terry pipes in. “It’s where all the kings and queens of Norway were crowned.”

As we are speaking, a large bright green service boat is manoeuvring into the reserved space behind us, using its bow and stern thrusters to come in sideways like a crab. There isn’t a lot of distance between us and them.

“We’ll be here for two days”, one of the crew tells us. “We’re one of the exhibits for the aquaculture conference. Now we have orders to get to and clean and paint everything.”

“Anyway, we need to get going”, says Chris. “We still have 20 miles to sail tonight, then we have a lot of packing to do in the morning. Perhaps we’ll see you here next year.”

We wish them the best for their homeward journey. Shortly afterwards we wave to them as they motor out of the harbour.

In the morning, we unload the bikes and cycle into town. We decide to attend to the boaty issues before we do the touristy bits, and stop off first of all at RiggMasters, a company specialising in rigging. We had been recommended them by the rigger who had repaired our VHF radio down near Bergen, and who had warned us that some of our mast shrouds were starting to fray and should be replaced soon. John, one of the bosses, promises to come and have a look at our boat in the morning. While we are there, we mention the batteries.

“I’ve actually got a couple of spare batteries you could borrow to finish your trip”, he says. “They’re second hand, but only a year old. You can bring them back afterwards if you don’t want to keep them, but you can have them for half-price if you want to keep them. I can bring them to the harbour if you like. But you will have to carry them down to your boat yourself. They’re pretty heavy, and my back is not up to it.”

I wonder if my back and knees are up to it too, but it’s an offer we can’t refuse.

“Let’s have lunch now, then go and see the Cathedral”, says the First Mate.

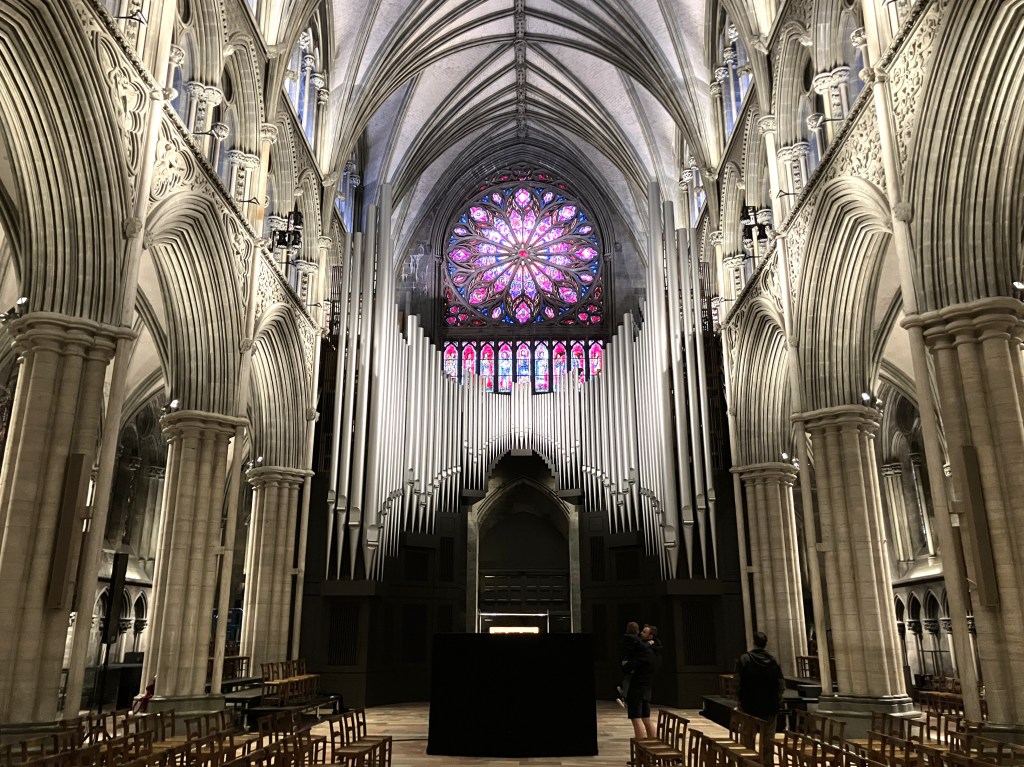

Nidaros Cathedral, the Crown Jewels, and the Armoury are all in the same complex. We buy tickets for all three. First up is the Cathedral.

“It’s absolutely stunning!”, exclaims the First Mate, once we are inside. “Think of the effort that has gone into building it all. No wonder the kings and queens of Norway like being crowned in here.”

“The Cathedral is built over the remains of King Olaf II, who lived from 995-1030 AD”, I read in the pamphlet. “He was instrumental in bringing Norway together as a country, and was made a saint as he was credited with introducing Christianity to Norway. This was despite not actually having all that much to do with it, and what little he did do, did fairly violently in that people who refused to become Christians had their heads cut off. But apparently miracles started happening after he died, which resulted in the Cathedral becoming a major pilgrimage centre in medieval times. These days they are trying to resurrect some of the major pilgrim trails to Trondheim, both for those wanting the spiritual experience, but also for recreation.”

“Ah, yes”, says the First Mate. “I remember that German girl telling us all about it when we were in Kökar in the Åland Islands last year. Don’t you remember that one of the routes, St Olaf’s Waterway, ran past the marina?”

We find ourselves standing in front of a Norwegian flag and a British Royal Navy White Ensign hanging in one of the transepts. A young woman in religious attire comes over.

“Hello, I am an assistant priest here”, she says, a friendly smile on her face. “Can I help you? Are you puzzled about why the British flag is there? A lot of people are.”

“Well, it belonged to the British warship, the HMS McCoy”, she continues before I can answer. “It was the first Allied ship to enter Trondheim in 1945 after the war. The other one is the Norwegian Royal Ensign from the ship that brought King Haakon VII back from his exile in London a month later.”

Suddenly there is a burst of music from the massive pipe organ over the entrance. It’s the theme music of Chariots of Fire. Not quite what we had expected in a cathedral, but it is nevertheless stirring as the deep basses reverberate around the magnificent acoustics.

We sit and listen to it, deep in our own thoughts.

“It’s amazing to think that my great-great-grandfather was here in 1889”, I say, when it is finished. “His letters say that it was being renovated at the time. Apparently it had fallen into disrepair, so they started major work on it in 1869, which wasn’t really finished until 2001. So we are quite lucky to see it in its finished state after 130 years of rebuilding. The original workmen in 1869 would never have seen the fruits of their efforts.”

We walk over to the building housing the Norwegian Crown Jewels. Unfortunately, we are not allowed to take photos.

“Never mind”, says the First Mate. “Here’s one of the coronation. You can take a photo of that to put in the blog. Now let’s have a quick look at the Armoury.”

The Armoury is next door. We learn of the region’s military history from the Viking Age through to the Middle Ages, wars with Sweden, and, of course, the Nazi occupation during WW2. One thing I hadn’t really appreciated before was the leidangr system that started in Viking times and continued for some time afterwards. All free farmers of a local area had to assemble at periodic intervals and contribute to maintaining a ship and manning it to defend the country or participate in raids abroad. Men had to provide their own equipment and provisions.

“Norway has certainly had a turbulent history”, says the First Mate as cycle back to the boat.

“Don’t forget that they dished it out as well”, I say. “Most of Europe was terrified of them at one stage.”

“I’ve booked a stolkjarre for ten o’clock”, Mr Fairlie says at breakfast. “I was planning to go out to the Leirfossen. It’s a waterfall just on the outskirts of Trondheim. About half-an-hour’s drive. Apparently it’s quite spectacular. You are most welcome to join me if you want.”

“Thank you”, says the minister. “Very good of you. I should like that very much.”

The light, two-wheeled cart drawn by a single horse rattles slowly through the cobbled streets leading away from the quays. There is a smell of tar, fish, and salt in the air, causing the elderly man to draw his breath in sharply. Passing the timber warehouses of Bakklandet, they cross the old bridge with its carved wooden gates, then follow the rough country road along the Nidelva River. Beyond the town the road turns dusty and uneven, the packed earth and loose stones jolting the cart at every rut. Farms dot the slopes, their fields bright with ripening grain, and here and there the travellers glimpse women rinsing linen in the river and children driving cattle along the verge.

As the valley narrows, the low roar of water grows stronger, until at last the Leirfossen appears—a foaming white torrent pouring between dark rocks, its mist rising above the birches. The two men climb down from the stolkjarre and stand at the small viewpoint, absorbing the scene.

“There’s an enormous amount of power there”, says Mr Fairlie eventually. “You know, it’s a pity that it can’t be harnessed in some way and used to benefit mankind. A power station, for example. Think of it. Machines running without smoke or steam, lights in the streets after dark, electricity in every house in Trondheim. Maybe even powering the trams one day.”

“I like it the way it is”, says the minister. “Why does our modern society have this perpetual urgency to control nature? What’s wrong with the machines we’ve got? We don’t need trams without horses. The old ways have stood the test of time.”

“And yet it’s the new ways that will build the future, my old friend”, says his companion. “The river’s strength will eventually be harnessed to light the city, believe me. Wait! If I am not mistaken, I think I see the young Mr Hunter-Blair over there with his new bride. Fancy meeting our neighbours here so far from home. I suppose we should go and pay our respects.”

“Did you see the waterfall?”, asks the First Mate, when I get back from my cycle ride.

“Well, sort of”, I say. “But it’s not a waterfall any more. It’s been converted into a power station. Mr Fairlie was right.”

“Remind me who Mr Fairlie is again?”, she asks.

“Just a friend of the family”, I answer. “And I stood in some seagull poo.”