After lunch the next day, we set off to catch the north flowing tide to take us to Strangford Lough five miles up the coast. We can only enter the Lough on a rising tide, when the water is flowing in from the sea through the Narrows to the Lough proper. Apparently, something like 400 million gallons of water pass in and out through the Narrows twice a day. Currents can reach 7 knots in each direction and we would have no chance of making any headway against that – instead, we would be carried back out to sea.

Entering Strangford Lough – the current starts to flow faster.

We begin to be swept along by the current, imperceptibly at first, but eventually at such a speed that trees, houses, churches, fields, and cars on the far shore pass quickly out of our sight. The water boils angrily as it encounters some underwater obstruction or cross current, but we are swept mercilessly onwards. It is out of our control now – we are committed to sail up the Lough – going back is no longer an option. There is nothing we can do except steer and avoid any obstacles by staying as much as possible in the middle of the stream. Our speed increases to 6 knots, then 7, 8, 9 and eventually reaches 11.4 knots. That is the fastest that Ruby Tuesday has been on the whole trip!

Top speed – 11.4 knots!

We pass a peculiar-looking structure in the middle of the river looking like a bird hanging its wings out to dry. We learn later it was a tidal stream generator to generate electricity from the powerful currents. At one point, the current sweeps us towards it, and we have to take evasive action not to hit it, sweeping past with only metres to spare. Apparently some yachts have hit it, and have lost their masts as a result. We shudder as we think of what could have happened.

The SeaGen construction.

As we approach the small village of Strangford on the western side and its counterpart Portaferry on the eastern side, the ferry connecting the two begins to cross in our path. We slow down as best as we can, cutting the engine, but it makes not much difference, and we slide somehow to its stern, avoiding it more through luck than good management. Strangford Lough is proving to be a bit of a slalom! In the excitement of passing the ferry, the current almost takes us beyond the entrance to the small harbour, but we slew ungracefully into an eddy out of the main stream, pause for a moment to regain our aplomb, and cruise slowly to the pontoon, looking around surreptitiously to check if anyone saw our ungainly manoeuvres. Nobody seems to have, and we are able to resume our pretence of knowing what we are doing. We tie up to the pontoon and explore the village.

Trying to avoid the ferry between Strangford and Portaferry ferry at 10 knots!

Tied up to the pontoon in Strangford village.

We decide to eat at the Cuan Inn in the village square. It seems that the cast of the Game of Thrones stayed here when they were filming some episodes at the local Castle Ward, about a mile from here. In the series it is known as Winterfell Castle. While we are waiting for our food to arrive, the proprietor, Peter, comes over and introduces himself, sits down and begins to tell us of some of the cast, what they liked to eat, and of what is was like filming some of the scenes. He shows us the ornately carved wooden door that was made especially for the series and now occupies pride of place near the main bar. We decide that the Northern Irish are nothing if not chatty!

The Game of Thrones door, Cuan Inn, Strangford.

We stumble back to Ruby Tuesday, only to find that we are nearly hemmed in by the ferry, which has stopped for the night. We can just about squeeze out if we need to, so it is lucky we don’t have any plans to go anywhere else for the rest of the evening. The ferry winks at Ruby Tuesday as if to say that she will be safe with her.

Hemmed in for the night by the ferry!

The next morning, we take the self-same ferry across to Portaferry, and visit the local museum. As we look a giant map of the village as it was in 1790, we are approached by the museum director.

“He changed his name, you know”, he says. ”So that he could marry the woman he loved.”

“Who was that?”, I say.

“Andrew Savage”, he responds. “The local land owner. The Savages are one of the old families of the area and used to own the village. House is up behind the village. Andrew fell in love with a girl, but her father said that he didn’t want his daughter marrying a savage, so he changed it to Nugent. He went from being a savage to a new gent, see?”. He laughs. We laugh politely too. We wonder how many times he has repeated that one.

Map of Portaferry in 1790.

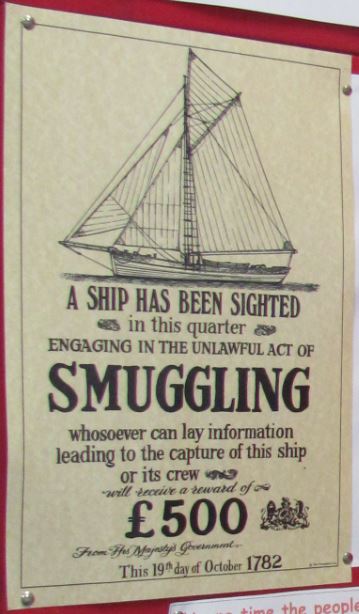

He tells us that the place used to be quite a haven for smugglers. Around 1700, the British government slapped taxes on tea, coffee, whiskey, tobacco, spices, chinaware, cotton and many other items. Many of these items were imported from France via the Isle of Man into Portaferry where duty had to be paid, but the numerous small bays around Strangford Lough were ideal for smugglers to off load goods from the ships before they came into harbour, leaving only some of the cargo to arrive legally. The illegal goods would then make their way inland concealed in baskets of fish. The problem for the excise men was that most of the local people didn’t see why they should have to pay duty for life’s luxuries, and actually supported the smugglers. Even the local gentry saw it as a good investment. Stiffer and stiffer penalties were introduced, from fines, transportation to the colonies, and even death. Rewards were paid to informers. Despite all this, smuggling flourished, and it was only the formation of the Coastguard in 1822 that brought it under control. Will such smuggling start again because of Brexit, I wonder?

Wanted for smuggling. Not Ruby Tuesday!

The next exhibit is of the SeaGen project that we nearly ran into in the Narrows the day before. It seems that it was a commercial electricity generator for some years, but was sold to another company and is now being dismantled. Now we could see how the whole thing worked – giant propellers like wind turbines could be raised and lowered at will into the current. Apparently, it was very successful and could produce 1.2 MW – enough power to supply all the households in both Strangford and Portaferry. The director can’t understand why it is being dismantled as it could have kept on being productive.

The SeaGen tidal power generator.

However, it seems as if other devices are being tested, including one that looks like a model aeroplane on a tether which apparently is much more efficient, so perhaps Strangford Lough will continue to play a role in Northern Ireland’s renewable energy programme. We hope so.

A new tidal power generator.

We wander back through the village. A group of cyclists just off the ferry are enjoying refreshments at a café before they continue. Bikers astride their Harley-Davidson’s roar noisily through the narrow streets as they continue northwards. A family visit the derelict 16th century tower-house castle, another of the Savage family properties, before climbing back into their car and driving on. A dilapidated shop advertising ‘Needful Things’ has long since closed. Several other shops are also boarded up. There is a general air of decline about the village, as though it has seen better times, a place now that people don’t go to but just pass through instead. It makes us feel sad.

Portaferry Castle.

No longer needed?