“Look”, says the First Mate. “You can see the place where we anchored last night, and the bridge that we came under this morning. And I think I can just make out Ruby Tuesday down there.”

We had arrived that morning at the small village of Skjerjehamn, not far from the entrance to the vast Sognefjord. Previously it had been a bustling trading port, transportation hub, and administrative centre, when ships were the most important modes of transport on the west coast of Norway. That all changed with the arrival of cars and the building of roads and tunnels. All that remains now of the settlement is the small harbour and some of the warehouses, one of them having been converted into a restaurant.

We had set off after lunch, and had walked the path from the harbour over moorland to the summit of Vesterfjellet, a local peak overlooking Ånnelandsund. It’s a hot day, so we had packed some biscuits, apples and bottles of water, which we are glad to have when we reach the top.

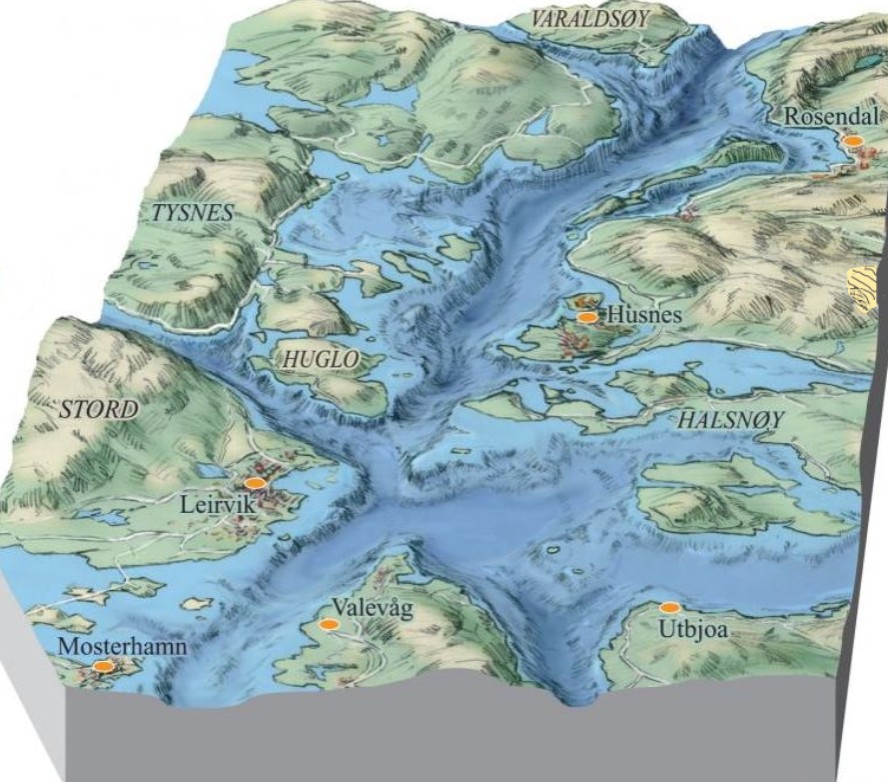

“This direction is just as spectacular”, I say, pointing to the north. “All those islands and fjords. That big one in the distance must be Sognefjord. That’s where we will be sailing tomorrow if all goes well.”

On the way back to the harbour, we pass the statue of Olaf V, King of Norway.

“The City of Oslo commissioned a famous sculptor by the name of Knut Steen to create a statue of King Olav V”, a woman tells us. “However, when it was finished in 2006, they didn’t like it as the outstretched arm was too much like a Nazi salute, and they refused to display it. It was put up for auction, and the owner of the local aquaculture company decided that it would fit very well in Skjerjehamn. He put in a bid, it won, and the statue has been here ever since.”

“Olav V had been a popular king, especially as he had been a focus of Norwegian resistance against the Nazis, as well as being a symbol of Norwegian independence”, says her husband, joining us. “So having him give a Nazi salute wasn’t seen as being in the best taste.”

It doesn’t really look like a Nazi salute, I think. His arm is bent, not straight. He looks more like he is waving goodbye to someone. But far be it from me to get involved in national sensitivities.

The next afternoon, we push on towards Sognefjord, stopping at the small town of Eivendvik to stock up with provisions. We decide to anchor overnight in the bay at Rutledal.

“This looks a good spot for fishing”, says the First Mate after dinner. “I think that I’ll have a go.”

With our fairly miserable record to date of catching fish, I am somewhat sceptical of any success. Still, if she wants to waste her time, that’s up to her.

She ties on a spinner, and begins casting.

“I think that I have caught something!”, she shouts after ten minutes. “Come and help me!”

I imagine it to be a piece of seaweed or an old tyre. Instead it turns out to be a fine specimen of a fish. A pollack, to be precise. We manage to land it without it getting away, which in itself is an achievement.

“We’ll have it for dinner tomorrow”, she says. “I’ve heard that pollack are best left for a day or so.”

The next day, we reach Vikøyri, a town halfway up Sognefjord.

“The guide book says that there is a traditional stave church here”, says the First Mate. “We should try and see it.”

Following a map the Visitor Information lady has given us, we walk up to the Hopperstad stave church. Unfortunately, a bus load of tourists arrives at the same time.

“Never mind”, I say. “At least we can join their guided tour. It looks like a young history student is doing it again.”

“They always seem so enthusiastic”, says the First Mate.

“They still have all their dreams in front of them”, I reply. “No wonder.”

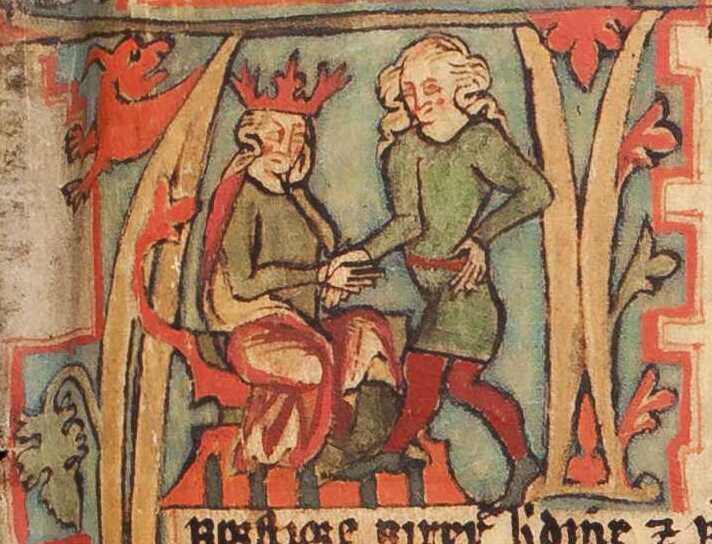

“The church was built around AD 1130”, the guide tells us. “After the Viking Period. Many of these type were built throughout Europe, but for some reason only those in Norway have survived. Out of the estimated 1000 there used to be, only 28 are now left.”

“Do you remember that one we saw in Lillehammer when we were with Ståle and Gunvor?”, I whisper to the First Mate. “We have only 26 to go.”

“Shssssh”, she hisses. “I am trying to listen.”

“You’ll see that the basic structure consists of eight-metre high posts held together with rafters, with vertical planks filling the gaps between them”, the guide continues. “Note that it stands on a stone base, which has protected the wood from rotting. Even so, it fell into disrepair, but luckily it was faithfully restored in 1880s.”

“What do the carvings on the gables signify?”, someone asks.

“I am glad you asked that”, she says. “They are the heads of dragons or serpents. A hangover from Viking times. You are probably familiar with the carvings on the prows of their long-ships, which were supposed to ward off evil spirits, trolls, and even bad weather. When Christianity came along, there was an initial fusion of Christian and Old Norse beliefs, so these dragonheads were supposed to protect the church in the same way as they had done the long-ships. Now, let’s go and have a look inside.”

It’s dark in the church, and it takes a while for our eyes to adjust.

“Miscarried foetuses and children who died before baptism weren’t allowed to be buried in the churchyard”, the guide continues. “So they buried them under these flagstones you are standing on, hoping they would go to heaven anyway. This practice carried on right up to the 19th century, when it was discontinued because of the smell.”

There is an uncomfortable shifting of feet.

“I am surprised it took them several hundred years to notice it”, whispers the First Mate. “I wonder if church attendance was falling off?”

“And over here, there are some runic-like inscriptions”, continues the guide. “They are generally pleas by people for God to reward them with a good harvest or success in business. They are not true Viking runes.”

The next day we push on. We pass Vangnes with its giant statue of Fritjof the Bold, commissioned by Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany in 1913.

“They certainly seem to like giant statues in these parts”, says the First Mate. “I wonder who Fritjof the Bold was?”

It turns out that Fritjof was one of the legendary heroes written about in the Icelandic sagas, supposed to have lived in the AD 700s. The story is that he was the strongest, bravest and fairest in the kingdom of Sogn, the area we are in at the moment, and where the Sognefjord gets its name. On the other side of the fjord to Fritjof lived the king with his two sons, Helgi and Halfdan, and daughter, Ingeborg. The king and Fritjof’s father went off to war and were killed, so the four children were brought up by a foster family. Helgi and Halfdan eventually took over the kingdom, while Fritjof and Ingeborg fell in love. The two brothers were intensely jealous of Fritjof’s good looks and prowess, so they sent him off to Orkney, burnt his house down while he was away, and married off Ingeborg to an old king of a neighbouring kingdom, Ringerike. When Fritjof came back from Orkney, he befriended the old king, and just before the latter died, was appointed as the carer of Ingeborn and their child. After his death, Fritjof and Ingeborn marry, he becomes king of Ringerike, and declares war on his two brothers-in-law. He kills Helgi, subjugates Halfdan, and becomes king of both kingdoms.

“Sounds like a fairly typical functional family history for a Viking”, I think.

Kaiser Wilhelm I of Germany used to holiday in this area, and was so taken with Fritjof’s story that he decided to have the giant statue made and erected in a prominent place on the Vangnes spit where all passing sailors would be able to see it.

“Wilhelm had pretensions to being a great Emperor himself”, says the First Mate. “So I am not surprised he liked stories like this.”

Towards the end of Sognefjord, we turn right into Nærøyfjorden, our destination. The fjord narrows, with almost perpendicular cliffs on both sides. Trees cling precariously to any nook or cranny they can find. The water is a deep green colour, and so clear that we could see the bottom if it wasn’t 300 m below us. The tallest mountains still have pockets of winter snow and ice nestling on their northern slopes. It’s stunning.

“No wonder it’s a UNESCO World Heritage site”, says the First Mate.

We reach Gudvangen, the small town at the top of the fjord. There is only one pontoon for guest boats. Luckily it is empty. We tie up.

“You can’t tie up there”, a girl teach kayaking skills to a group of people calls out. “One of the tourist boats comes in there. Sailing boats can only go on the other side.”

I had been going to tie up on that side originally anyway but it had looked a bit shallow for our keel, so I had chosen the other. In the event, there is 60 cm clearance – not a lot, but enough.

The elderly gentleman asks the driver of the stolkjarre to stop at the hotel at the top of the pass for lunch. It had been a long morning – the two men had taken the train from Bergen to Voss, then a stolkjarre the rest of the way to Gudvangen.

“Stalheim Hotel”, says Mr Fairlie, his travelling companion. “It was only built four years ago. I’ve heard that you have the most exquisite views from here. Let’s see if we can have a table in the garden. It’s fine enough weather to sit outside.”

“I have never seen such natural beauty in my life before”, says the elderly gentleman, as they are shown a table near the edge of the precipice. “What a most wonderful valley! I am sure that nothing else in Europe can surpass it for grandeur.”

“I think I will have the prawn sandwich, please”, says the First Mate to the waitress. “And a coffee.”

“Me too”, I say. “Except I’ll have tea. Earl Grey, please.”

We are at the Stalheim Hotel at the top of Nærøyfjord. Earlier in the morning, we had left the boat in Gudrangen and had taken the No. 950 bus up the valley to the hotel for lunch.

“It’s amazing to think that my great-great-grandfather was here in this very place in 1889”, I say to the First Mate. “Admittedly, it’s not quite the same hotel, as it has burnt down no less than three times – in 1900, 1902 and 1959. This one dates from 1960. But the view will be the same.”

“Well, it certainly is stunning”, says the First Mate, as our lunch arrives. “But I am a bit surprised that he came on this cruise without his wife. I wonder why that was? Do you think that they had had a row?”

“It was quite acceptable for ministers and professional men to go on cruises without their wives”, ChatGPT tells us. “It was more to do with the cost than anything untoward going on. A cruise like this would have cost £10 in those days, plus a few pounds extra for side excursions. With a minister’s annual stipend for a rural parish being around £150, it would have been quite expensive.”

“Men always seem to get the privileges”, she sniffs. “I wonder what she thought about it?”

“Have you heard how your son Quinton is?”, asks Mr Fairlie, taking a sip of his tea. “Where was it that he went again? Canada, wasn’t it?”

“Well, it was Canada”, the elderly gentleman replies, the emphasis on the past tense. “At first. He managed to get farm work there for a while, but he had an accident in a threshing machine and lost some fingers on his right hand, so he wasn’t able to work for a while. Then the Americans brought in their Homesteading Act in which 160 acres of land were given free to those who moved there. It was the time the Northern Pacific Railroad was being put through, so the area was opening up. So he decided to move down to North Dakota, build a house, and make a living from farming. By all accounts he is doing quite well there.”

“It’s funny how both your boys ended up farming”, says Mr Fairlie. “What with you being a minister and all. None of them interested in being a man of the cloth, then?”

“They used to spend a lot of time on their uncle’s farm in Ayrshire when they were youngsters”, the elderly gentleman answers. “My wife’s brother Quinton. That’s probably where they got it from.”

“Well, you have to admire them for leaving the Home Country”, says Mr Fairlie. “More opportunities there than Scotland, at least. I am sure they will both do well. Anyway, if you are finished, we had better move on. We have to negotiate the Stalheimskleiva road down from here now before we get to Gudvangen. It’s very steep.”

“It certainly is steep”, says the First Mate. “It’s bad enough walking down. Imagine taking a horse and trap down here. Look at the hairpin bends.”

“I read that they often used to walk down steep parts themselves, to spare the horses”, I say. “But I agree. If the horse slipped or skidded everything would just go over the edge.”

Halfway down we stop to look at the Sivlefossen waterfall.

Eventually we reach the bottom with everything more-or-less intact, apart from some protesting knees.

“Sometimes I feel I am getting too old for this sort of thing”, I say.

“Me too”, says the First Mate. “But don’t worry. Here comes the bus. We’ll be back in Gudvangen in no time. Just be thankful we are not on a stolkjarre.”