“Look!”, shouts the First Mate, pointing to a steep cliff to our port side. “You can see Hammershus castle up there. It’s hard to believe that we were up there yesterday. It looks quite impressive even from down here.”

We had left Allinge in the morning, edging our way carefully out of the small harbour with its dog-leg entrance, and are just rounding the northern point of Bornholm Island. The wind is from the north-east, giving us a comfortable beam reach as we head for Ystad, back on the Swedish mainland. Between here and there, however, we must cross a Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) for the big ships, which the rules say that we need to do at right angles to minimise the amount of time crossing it.

“It reminds me of the time we crossed the English Channel”, I say. “It was like being in a pinball machine – no sooner had we dodged all the ships coming from one direction, we had to face a whole lot more coming from the opposite direction. Let’s see if we can get across here without altering our course.”

“Be careful”, says the First Mate. “We don’t want to have an accident at this stage.”

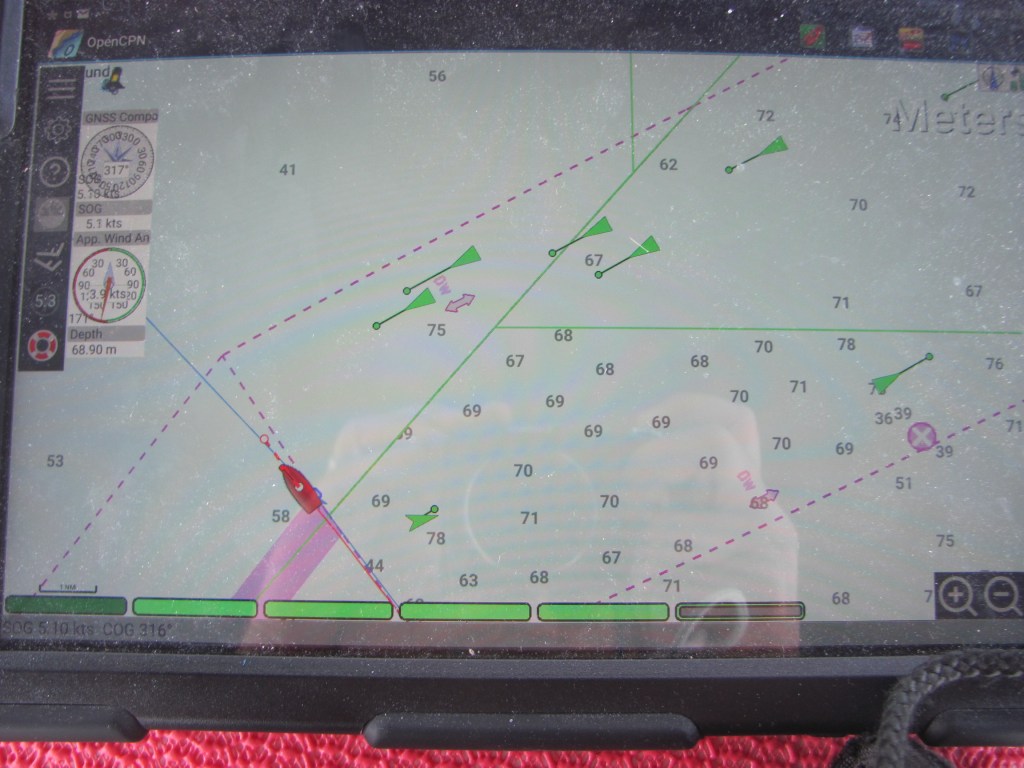

We manage to make it through the north-bound lane without too much trouble. But traffic in the southbound lane is heavy, and there are five ships in a cluster that we need to avoid. The AIS tells me that we will pass behind the first three comfortably, but that we will pass in front of the fourth one with just 15 m as the Closest Point of Approach (CPA). That is a little bit too close for comfort! Hoping that the wind might strengthen and give us a bit more speed, or even drop so that we slow down, I keep an eagle eye on the AIS as we cross, but the CPA remains obstinately the same. As our paths converge closer and closer, I chicken out and decide to heave-to. As the ship passes about 100 m in front of us, we can see some of the crew leaning over the guard rails and smoking.

“Phew”, breathes the First Mate in relief. “That was pretty close.”

“Yes, I even noticed that it was Gauloises they were smoking”, I say.

Once clear of the TSS we alter our course to the east. As luck would have it, the wind shifts and drops, as does our speed.

“We aren’t in any hurry”, I say. “Let’s just take it easy and enjoy the sunshine.”

At a stately three knots, it takes most of the afternoon before we reach Ystad, our destination for the night.

“Better look out for that ferry over there”, calls the First Mate, pointing to something on the horizon. “It looks like it’s heading for Ystad too.”

“There’s plenty of time”, I say. “It’s miles away.”

But it’s a catamaran and travelling fast. In a few minutes it is just behind us. It blows its horn to tell us to get out of the way. We motor as fast as we can to a red buoy, and take a line just outside it so that the buoyed channel is clear. The ferry slows down and cruises past us.

Obsession is already there. We aim for the berth just behind her. Ingemar gives us a hand tying up.

“Ystad is a pretty enough place”, he says over a cup of tea. “It’s a former Hanseatic town, and the church and some of the old half-timbered houses are worth a look. It’s just a short walk into the centre of town from here. Ystad’s other claim to fame is that it is the place where the Wallander crime series is set.”

The First Mate has watched the Wallander series, but I haven’t. I make a mental note to try and see it on iPlayer over the winter.

In the morning, we walk into the town centre. We come across the Sankta Maria Kyrka, built in the 1200s in Brick Gothic.

“The guidebook says that the church still has a Tower Watchman”, says the First Mate. “His job is to climb the tower every night and keep an eye on the city. He blows a horn every 15 minutes from 2100h to 0100h to signal that everything is OK. If the horn doesn’t sound, it means that there is a problem, like a fire or something. It’s an old tradition from the 1700s that has been kept alive. Apparently, it has been the same family who have been doing it all that time.”

“I wonder what they do if he is sick or on holiday?”, I say.

Next to the church is the Latinskolan, or Latin School, that was used in medieval times to teach Latin to the sons of clergymen and the local elite to prepare them to go to university.

A little bit further on, we come to the Klostret I Ystad, or Greyfriars Abbey, originally a Franciscan monastery. There is a small museum attached to the side, but unfortunately it is Monday and it is closed.

“The book says that the Franciscan order wore grey habits”, says the First Mate. “Hence the Greyfriars name. They emphasised the simple life and travelled around the countryside preaching, caring for the poor and sick, and living off alms given to them by those who could afford it. The friary was a place they could come back to for meditation and contemplation.”

It’s lunchtime. We join the queue at a place called ‘Maltes Mackor’ that is famous for its tailor-made sandwiches, and eventually watch in mouth-watering anticipation as each of our sandwiches is ‘constructed’ with loving care.

“Well, it took a while”, says the First Mate, “but I have to say that it was worth it. They taste marvellous.”

After lunch, we explore the narrow streets flanked with half-timbered houses. Per Helsas Gård was a farmhouse built just inside the city walls following their curvature. Nowadays, it houses a number of craftsmen, with an open air café in the old courtyard.

Pilgrändshuset is a residential house joined to a warehouse dating from around 1500 AD.

The Änglahuset is another farmhouse, so called because of the decorative angel figures under the eaves.

In the evening, we ask Ingemar over for a drink.

“Did you hear that the Falsterbo Canal is closed for us?”, he asks, as he sips his Weizen beer. “They are repairing it. It’s open for south-bound traffic this week, but not northbound, then next week they are switching around. Unfortunately, we both need to go through this week.”

Falsterbo Canal was built during WW2 to allow Swedish vessels to continue sailing to and from the North Sea while avoiding the mines laid in the Öresund by the Germans. It is still maintained, but is now mainly used for recreational boats wishing to take a short cut to avoid the long way round through the Öresund.

“Yes, I read that somewhere”, I say. “We are planning to go round the outside and perhaps stop in Skanör for a night.”

Obsession leaves at 0700 in the morning. We are a bit more leisurely, and don’t get going until around 1000. The wind is from the port quarter, but shifts to directly behind after a couple of hours. Sailing with the genoa only, we still make around six knots. As we reach the Öresund and turn northwards, the wind strengthens. I take out the mainsail, put in two reefs, and we still manage to make more than eight knots on a close reach. I glimpse Obsession on the AIS far ahead, already past Skanör, heading for Malmö.

“8.2 knots!”, says the First Mate. “We don’t often do that speed. And with a double reef too. But it was heeling a bit too much for my liking.”

We stop for a night at Skanör, then set off in the morning for Malmö.

“This will probably be the last sail of the season”, I say. “I feel a bit sad that it’s all over for another season.”

“Me too”, says the First Mate. “Better make it a good one then.”

And it is. The wind is still an easterly, and blowing 24 knots, so we sail double reefed again. Before long we have passed the Lillgrund windfarm to our port, and are approaching the Öresund Bridge.

“Keep an eye out for Saga Norén”, I call out to the First Mate at the bow. “They might be making another episode of The Bridge. And try to ignore the dead bodies, especially the ones sawn in half.”

With the wind blowing, she doesn’t hear me. Probably just as well.

We pass under the Bridge and arrive at the Limhamn marina in Malmö. The harbourmaster has asked us to tie up to the second pontoon. Ingemar sees us arriving and comes to catch our lines.

“I’ve just been servicing my heat exchanger this morning”, he says over lunch. “You need to do it every couple of years or so, or else the small pipes inside it will get blocked up with scale. I have rigged up a pump and some tubes that circulate phosphoric acid through the sea water side of the exchanger for an hour or so. That dissolves all the scale, leaving it nice and clean again.”

Rather than having a radiator like cars do, the heat exchanger takes in sea-water and uses it to cool the hot coolant circulating through the engine. That way sea water doesn’t come in contact with the engine to cause corrosion.

“When was the last time we did that?”, asks the First Mate.

I have learnt that by ‘we’, she always means me.

“We haven’t done it since we have had the boat”, I say.

“It would probably be a good idea to do it”, says Ingemar. “Just to avoid problems.”

There is also a small leak in the cooling system that I have been meaning to do something about, and the mixing elbow that combines the warm sea-water with the exhaust gases also needs to be checked, so I decide to remove the whole assembly from the engine and take it home to do everything together. I spend the next couple of days getting it off. Like everything in boats, some nuts and bolts are almost inaccessible, and there is very little space for me to manoeuvre in the engine compartment.

“You need to lose a bit of weight”, sniffs the First Mate unsympathetically. “It’s all those peanuts you have been snacking on. I wouldn’t be surprised if you get stuck in there. Make sure you’ve got your mobile handy so you can call me.”

I finally manage to get the heat exchanger and the mixing elbow off. I change the oil and replace the oil and fuel filters. We pack away the sails, and take down the spray hood, cockpit tent, and the bimini. The new dinghy is deflated, rinsed in fresh water, and stowed. Clothes and other fabrics are stored in the vacuum packs and the air sucked out with the vacuum cleaner. Everything is ready for the winter.

“You know, we should take the opportunity to explore Malmö”, I say one evening. “Now that most of the winter preparations are done.”

“I was thinking the same”, says the First Mate.

The next morning, we cycle into town to explore. Malmö was founded some time in the 1200s when southern Sweden was actually part of Denmark. One story is that the name comes about from a young woman being ground up in a mill, but this is almost certainly untrue. In the 1600s, the city became part of Sweden under the Treaty of Roskilde. Then, in the 1800s, it was the first city in Sweden to industrialise, with the main focus on shipbuilding and textiles, but it was slow to adapt to the post-industrial period after the 1970s. However, with the opening of the Öresund Bridge, it has taken off again and is rebranding itself as a hi-tech, educational and cultural centre. In 2020, it was the fastest-growing city in Sweden, with 40% of the population coming from a non-Swedish background.

We come to a bronze statue of a number of people sitting on the back of a giant fish, by the Swedish sculptor Carl Milles. Called “Emigranterna“, it represents the large numbers of Swedish people who left their homeland to emigrate to the New World in search of a better life. Emotions of determination, hope and apprehension line their faces as they head for an unknown future.

“It’s ironic that large numbers of Swedish people left from here to go abroad to make a better life”, says the First Mate, “and now Malmö is the place that many immigrants arrive from third world countries to make a better life here.”

“Even more ironic is that there were tensions between the Swedes and the earlier settlers in America”, I say. “Especially the English-speaking ones, who saw them as culturally different in terms of language and religion. The Germans and Dutch didn’t like them much either, as they competed for jobs. But now they are well integrated into American society. What goes around, comes around.”

On the way back, we spot the ‘Turning Torso’, a 190 m high residential skyscraper built in 2005, and one of the tallest buildings in Scandinavia. It is the modern day icon of the city, replacing the shipyard crane that had previously been the Malmö icon, but since sold to South Korea.

“It’s certainly very eye-catching”, says the First Mate.

—–

It’s the last day – the day that we are leaving to drive to Germany to see the First Mate’s family, and then back to the UK.

On the way back from the shower block, I see a quick movement of something black near the rocks of the breakwater. It’s a mink. It stops and regards me intensely. I stare back at it. For perhaps five minutes we regard each other with curiosity, neither of us moving. It doesn’t seem to be afraid, despite there being only two metres between us.

What thoughts are going through its mind, I wonder? Do mink even have thoughts or a mind? Or emotions? Is it wondering what I am thinking? What would it be like to be a mink?

I think back to the essay written by Thomas Nagel “What is it like to be a bat?” that I had read during my student days. In it, he argues that consciousness has a subjective aspect that cannot be fully understood from an external, objective perspective. While we can study a bat’s brain physiology, we can’t fully grasp its subjective experience—what it is really like to perceive the world as a bat. We can imagine what it is like to be a bat, but that is still a human imagining what it might be like. Any attempt to reduce subjective experience to physical processes will always be incomplete.

And yet, there seems to be something shared in this brief encounter with the mink, even if it is just curiosity about the other. Is curiosity a shared experience? If so, there may be others. Or am I anthropomorphising?

“Come on”, calls the First Mate from the boat. “We need to pack the last things into the car and lock up. We’ve got a long journey in front of us.”

The mink scampers off to a gap in the rocks to re-join its world. I return to my world of other humans and their technology. The fleeting connection between very different minds is gone.

“See you next year”, I call after it.