“According to the harbour guide, there’s supposed to be a hammerhead on the pontoon”. says the First Mate, peering through the binoculars. “But I can’t seem to see it. That would have given us plenty of room, but there seems to be just the pontoon. And it’s taken up with motor boats. We may have to raft up alongside.”

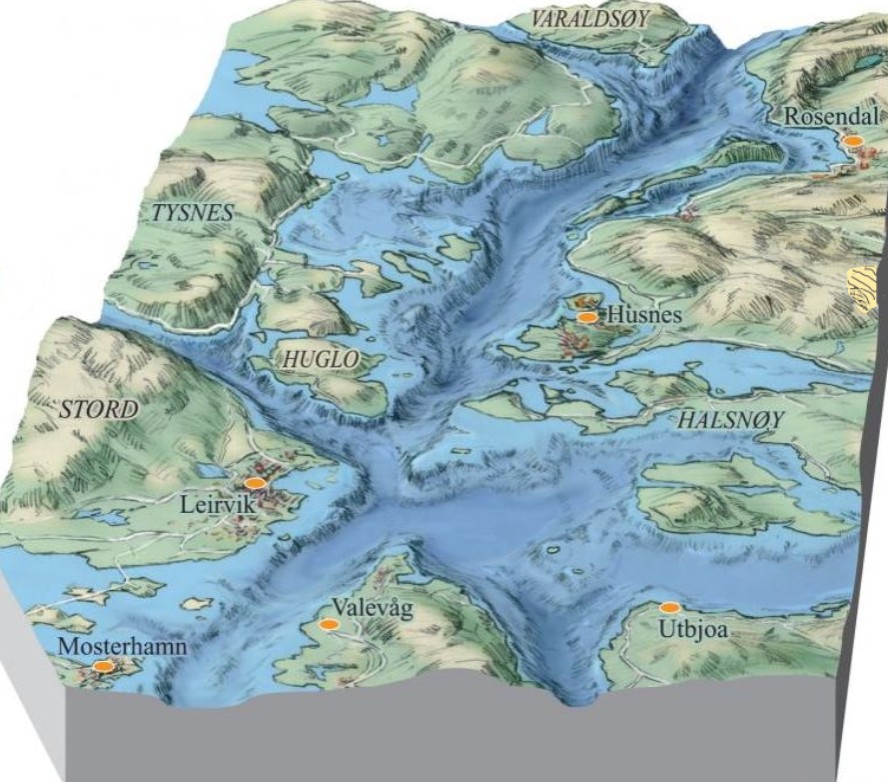

We are approaching the town of Geiranger at the top of Geirangerfjord, another UNESCO World Heritage site. We had set off in the morning from Sandshamn, and had had a pleasant sail up Storfjord then Sunnylvsfjorden, with the wind funnelling along the fjord behind us, before turning left into the short Geirangerfjord. In the distance, we see an army of campervans lining the waterfront, all with their skylights open in a vain effort to keep cool.

“Yes, there was a hammerhead here last year”, says the owner of the motorboat we raft up to. “But it was destroyed by the ice over the winter and they haven’t got around to replacing it yet. But I am quite happy for you to tie up alongside. You can get to the pontoon over the swimming platform at the back here. By the way, there is a thunderstorm due shortly if you haven’t heard already.”

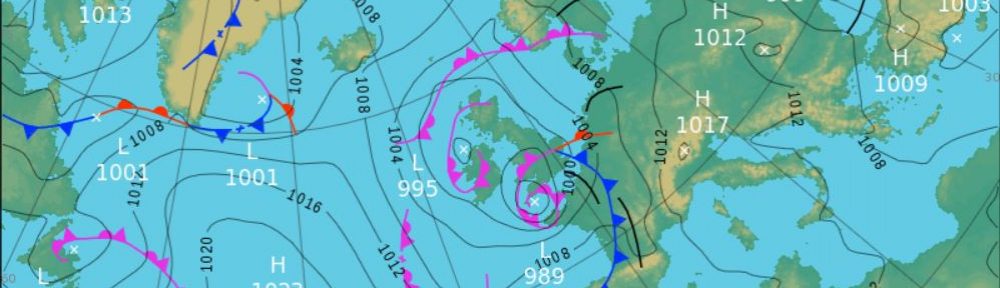

We hadn’t heard. Nothing was mentioned about it in the weather reports we had received.

“They are very spontaneous”, he says. “It’s because of all the heat we’ve been having.”

Sure enough, fifteen minutes later, the wind starts to blow fiercely and the heavens open. As if choreographed, all the campervan skylights slam shut as one. We just make it into the cabin without getting wet, and watch and listen in trepidation as torrential rain falls and lightening cracks overhead. The windspeed indicator reads 33 knots.

“I hope our mast isn’t the tallest thing around”, says the First Mate.

“I think the buildings over there are taller than our mast”, I try and reassure her. “Hopefully, the lightening will go for them first.”

Thirty minutes later, it is all over. The sun comes out, and the skylights on the campervans open again in unison.

“Phew, that was pretty intense while it lasted”, says the First Mate.

In the morning, we walk up to the Norsk Fjordsenter, where there is an exhibition on the mountain farms in the area. We had often seen these mountain farms clinging perilously to the steep cliffsides as we passed far below in the fjord, seemingly cut off from the rest of the world, with many not even visibly linked to the sea. As we had seen grass but rarely livestock, we had wondered what they actually farmed and how they transported their produce to the markets.

“Traditionally these mountain farms kept goats”, a panel in the exhibition tells us. “Pastures on the steep fjord sides provided grazing for them. The farmers produced brown and white goat cheeses and goat’s milk butter, all made according to traditional methods. Nowadays these farms may also keep sheep, cattle and Norwegian fjord horses.”

We taste some of the brown goat’s cheese.

“I can’t say I like it that much”, says the First Mate. “It’s a bit sweet for me.”

In one particular farm, the only route to it involved a short pitch of vertical rock that could only be passed with a ladder. The story goes that when the tax collector came to assess and collect the farm’s taxes, the farmer would pull the ladder up so that he couldn’t ascend any further, and he would have to go away empty-handed.

“I suppose the farmer thought he wasn’t getting much benefit from the state, so why should he contribute to its funding?”, says the First Mate. “There’s a certain logic to that.”

Life was precarious. Landslides and avalanches would sometimes sweep away entire farms, carrying the people with them. The worst of these was in the neighbouring Tafjord in 1934, when 2 million cubic metres of rock broke off and plunged down into the fjord below, causing a massive tsumani with waves up to 62 m in height and killing 40 people.

“Did you read that the next one they reckon will occur is at Åkerneset?”, says the First Mate. “Didn’t we pass that on the way in?”

We had indeed. A massive crack several hundred meters long and slowly widening each year threatens to collapse into Sunnylvsfjorden. Projections indicate that it could generate tsunami waves up to 70–80 meters high, drowning towns like Geiranger, Hellesylt, and Stranda within minutes. Luckily it is heavily instrumented to give warnings of its imminent collapse.

I shudder. “Perhaps we ought to get going”, I say. “I wouldn’t want to be underneath it when it goes.”

“You can walk up to one of the former farms that overlooks Geiranger town”, the woman behind the desk tells us. “It’s more for tourists these days, and there’s a restaurant there, but it gives you a good idea of what life was like in these remote mountain farms. You can then also walk on further to the waterfall if you like. You can even go in behind the waterfall for a memorable experience.”

“There’s a plateau more than 1000 feet up the side of the mountain behind us”, says Mr Fairlie to his older companion over breakfast. “And there’s a new road up to it that they have just completed this year. If you wish, we could take a stolkejarre and driver up there and see how they farm. There’s also a good view of the fjord on the way up.”

“I should like that”, says the minister. “As much as I like sea air, I need to avail myself of fresh air from the land for a short time.”

“Well, there will be plenty of that up there”, says Mr Fairlie.

“There’s a funeral on at the church today”, the driver of the stolkejarre warns them. “We may be delayed somewhat as the mourners arrive. The road around it is narrow and there isn’t much room for vehicles to pass.”

We take the footpath up to the farm. The funeral traffic is completely blocking the road into the town, and there is a considerable tailback. We squeeze past the best we can and start climbing the stone steps up the hillside to the farm.

“Wow, that was steep”, pants the First Mate. “I am really looking forward to having an ice-cream at the restaurant.”

It’s closed. There is a sign saying that the funeral wake is being held there. The same cars that were blocking the road far below are now all crammed into the small restaurant car-park.

Luckily we have some sandwiches and water, so we find a shady spot under a tree and rest before carrying on. Behind us some mountain sheep are chewing the cud for their lunch.

The elderly gentleman and his younger companion are already sitting there.

“We’re on a cruise around the fjords”, they tell us. “We have a day here in Geiranger, so we decided to take a side trip up here. It does one good to stretch one’s legs and to enjoy the views. It’s such a beautiful country. We are from Scotland.”

“Amazing”, I say. “That’s where we live. And we are also cruising around Norway. What a coincidence!”

We finish our lunch, say goodbye, and push on to the waterfall. It’s impressive.

We clamber down the rocky path to the side and edge our way gingerly along it until we are under the waterfall. It is a surreal feeling as tons of water thunder past us every second.

“It’s lucky there is a guide rail to hold on to”, I say. “It’s a sheer drop down there. I wouldn’t want to fall over.”

Soon we are damp from the spray in the air.

“Come on”, says the First Mate. “Take your photos, and let’s go. I’m getting quite wet.”

There is no sign of the elderly gentleman and his companion as we retrace our footsteps back down the path.

“They have probably gone back to their ship”, I say. “The ones we had lunch with. By the way, did you notice that the elder one looked a bit like me?”

“What on earth are you talking about?”, asks the First Mate. “We had lunch with a young German couple who were touring Norway in their car. Are you losing it, or is this just your vivid imagination again?”

The next morning, we cast off and motor slowly back along the route we had followed up to Geiranger.

“Look”, shouts the First Mate from the bow as she tidies up the ropes. “There’s the Seven Sisters waterfall. But there only seem to be five at the moment. I read somewhere that the number of sisters depends on how much rain there has been.”

Unusually, the wind is favourable when we reach Sunnylvsfjorden, and we are able to enjoy a pleasant sail back down the fjord with the genoa only. Normally in the fjords, because of the funnelling effect, the wind always seems to be against us, no matter which direction we are heading and which wind direction has been forecast.

A boat is coming up fast in front of us.

“It’s the Hurtigruten”, I say, peering through the binoculars. “It’s going to pass us to port.”

The Hurtigruten is the iconic Norwegian coastal express service operating between Bergen and Kirkenes near the border with Russia in the far north. Not only does it act as a daily passenger and cargo service, it is also possible to take scenic cruises on it.

“You are pronouncing it wrong”, says the First Mate. “It’s ‘Hurtig-ruten’, not ‘Hurti-grutin’. It means ‘Fast Route’, just like in German.”

In the late afternoon, we break our journey at the delightful little anchorage of Honningdal.

“It’s such a lovely peaceful spot”, says the First Mate dreamily, as we sip our wine in the cockpit in the evening. “With stunning views of the mountains and the fjords. If only those geese over there would stop being so noisy with all their honking, we could enjoy the peace and solitude.”

“Well, I suppose they are part of nature as well”, I say.

“Those sheds on the shore look like they have Boris Johnson haircuts”, I say, pointing to a cluster of boatsheds on the other side of the small inlet. “I think I might send the drone over there and get a shot of them.”

“Careful you don’t hit the power wires”, warns the First Mate.

We eventually arrive in Ålesund. There aren’t any spare berths at the small marina, and we have to raft up to another sailing boat with a Swiss flag.

“You look familiar”, says its skipper. “I think that we have met somewhere before. And I recognise your boat’s name. Ruby Tuesday. Out boat is called Sol Vita.”

We rack our brains. He gets there first.

“It was in Hanko in Finland”, he says. “Last year. Don’t you remember there was an armed forces flag day? My name is Christoph and this is Solvita. The boat is named after her, by the way.”

My memory stirs. “And we were both visited by the coastguard people as we were the only two foreign boats there”, I say. “They checked our VAT status, being a UK-registered boat. Then they went over to you on the other side of the pontoon.”

“We followed your route around the Baltic States”, Christoph says. “We nearly caught up with you in Riga in Latvia – we were in another marina, but we came to your boat one day to see if you were in, but you weren’t unfortunately.”

“That was probably the time we left the boat and took the bus down to Vilnius in Lithuania”, says the First Mate. “What a pity we missed you.”

“We left the boat in Latvia over the winter”, says Solvita. “I am actually Latvian. This year we have sailed from there, around Sweden and Norway, right to the top of Nordkapp in the far north of Norway. Now we are on our way back again. ”

We’re suitably impressed. That’s about 3600 nautical miles as the crow flies, not counting all the little bays, inlets and fjords they must have gone into. We are lucky if we manage to do half that in a season.

“We do do a lot of long passages”, says Christoph, seeing the looks of astonishment on our faces.

In the afternoon, we take the path to the top of the Aksla hill overlooking Ålesund. There are supposed to be 418 steps. I’ll take their word for it. The view from the top is stunning.

Later we are invited to Sol Vita for drinks.

“I studied law and then medicine at university”, Solvita tells us. “But I couldn’t really settle to a job in those areas. I had always enjoyed sailing ever since I was a little girl, and since I met Christoph I moved to Switzerland to be with him. We have been sailing every summer since then. A couple of years ago I had a go at writing a book. All in Latvian, I am afraid. It’s called ‘Purva migla’, or ‘Bog Fog’ in English, and is about a girl with a dark past who is trying to find herself. She travels far and wide in her quest, but starts to realise that the answers to the question of her past lie back where she came from.”

“It sounds interesting”, says the First Mate. “I like those sorts of books. You should translate it into English sometime.”