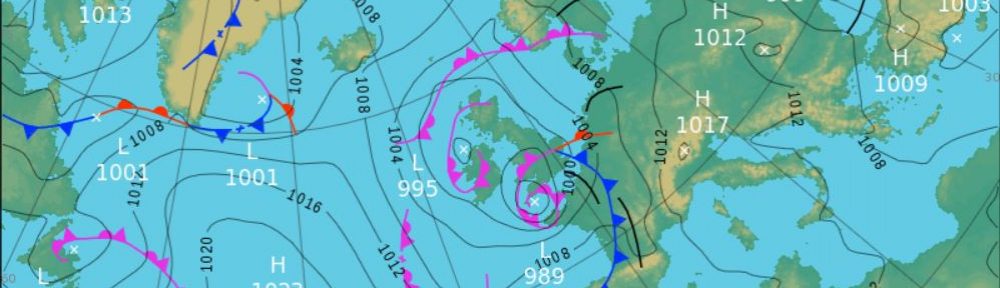

“We need to get an early start tomorrow”, I say. “The wind is from the north-west from about midnight, which is good for us as it will be on a reach and it should carry us more southards. The problem is that it is forecast to go then around to the south-west at around noon, which will then blow us north. So we need to get as much of the north-west wind as we can. I suggest that we leave at 0300 just as it gets light.”

We are planning the crossing across the Skagerrak from Sweden to Norway, a notorious piece of water that is essentially open sea. Depending on where we make landfall on the Norwegian coast it could be a distance of 60 to 90 nautical miles. As we are then heading south along the Norwegian coast and around the bottom, we want to get as far south in our crossing as we can.

“Ugh, I don’t like these early starts”, says the First Mate. “But I guess we have to do it.”

“Once we get going, you can go back to sleep”, I say.

We edge our way out of the harbour in the half dark, and with little wind in the protected area of Strömstad, we motor clear of the rocks and skerries north of the Koster Islands before raising the sails. As forecast, the wind picks up and we sail on a fast beam reach. Looking back, we see the sun begin to peep above the horizon.

“It’s times like this that I really love about sailing”, says the First Mate. “It’s so beautiful. Now, if you don’t mind, I am going to try and get a bit more sleep. Let me know if you need anything.”

“Just a cup of tea before you go”, I say.

The land disappears out of sight behind us, and Norway is yet too far to be seen. We are alone on the sea. The miles slip effortlessly under the keel, interrupted only by the passing of the ferry from Kiel to Oslo.

At mid-day, the wind drops to almost nothing. We consider starting the engine, but moments later, the wind starts again, this time from the south-west. Just as predicted.

“I’m always amazed how quickly these wind changes can occur”, says the First Mate, awake now. “You’d think that the change would be much more gradual than that, going around slowly. But it often happens all of a sudden.”

“I guess we must be at the boundary of two airstreams moving in different directions”, I say. “We would need to look at the wind map.”

As anticipated, the change in wind direction means that we will be pushed further north now. I do some quick calculations and work out that we should be able to make landfall at Risør, further north than I had hoped, but not too bad. By all accounts it is a pretty town.

Soon we are edging our way through the islands and skerries guarding the entrance to Risør harbour and tie up on the outside of the L-shaped pontoon.

“You need to report your arrival to the police if you have just come from Sweden”, the couple on the American-flagged boat in front of us tell us. “As well as the Customs. They came down to inspect us earlier in the afternoon. Luckily we had declared everything and paid the duty on it.”

We had heard that the Norwegian Customs were tightening up on the entry of foreign boats into Norway, and that it was highly advisable to be proactive and up-front in registering your arrival and declaring what you are bringing into the country. We had just heard a story of a British boat which had been heavily fined in the previous week for not completing their formalities correctly.

We had already declared online the small amount of alcohol we had in addition to the meagre limit we were allowed. I spend the rest of the day trying to phone the police in Oslo, but no-one seems interested. Eventually I reach the local police for the area.

“That’s fine”, the young-sounding officer on the other end says. “I’ll make a note of your arrival, and send you an email to confirm that you have entered correctly. Let me just find out if Customs want to come and see you. They are just in the next room.”

“No, they don’t need to see you”, he says on his return. “You are free to sail in Norway now. But don’t forget that if you want to leave your boat here over the winter that you need to ask them formally for permission after six weeks from the date of entry.”

“Well, that was all very easy”, says the First Mate, with a sigh of relief. “I thought they would at least come and search us, after what the Americans told us. We could have been real smugglers for all they know.”

Risør is a picturesque little town with all of its houses painted white. It has a strong maritime history, with many wooden boats being kept and maintained here, and an international wooden boats festival every August.

We climb up to the Risørflekken, a patch of bare rock painted white, overlooking the town. The story is that it was created by Dutch sailors in the 17th century as a navigational aid, and is still visible several miles out to sea. Its white colour has been maintained ever since then.

“Not quite”, says the First Mate. “I read somewhere that they painted it black during the Napoleonic Wars to stop the English boats from seeing it.”

In any case, it gives a good view over the town and the harbour. We sit for a while and watch the comings and goings of the small boats.

“Did you see that there is a pub here called ‘The Peterhead’?”, says the First Mate on the way back.

I had seen it. Peterhead is a major fishing port in north-east Scotland, where we live, and where we had kept Ruby Tuesday for a winter during the covid pandemic.

“I asked the landlord how it came to be called that”, she continues. “Apparently it was because of the strong timber trading links between Risør and Peterhead in the 18th and 19th centuries. A lot of Norwegian pine was taken from here to be used for shipbuilding and house construction in Scotland.”

The next morning, we head southwards from Risør. The wind is now from the north-east, and the Norwegian current is also flowing southwards parallel to the coast, so we have an effortless run down on the genoa only, passing Arendal, Grimstad and Lillestad. Past that, we have decided to take the Blindleia route, the inner route through the islands off the coast.

“The name translates as the Blind Alley”, I say. “There are a lot of nice anchorages on the way. The only thing is that it is very narrow in places, with the occasional sharp turn, so we will need to take it carefully. There is also a bridge at the beginning that has only 19 m clearance, which is a bit risky for our 18 m, but luckily we can join it a few miles further down. Better safe than sorry.”

“There seems to be a nice looking anchorage just close to where we join it”, says the First Mate. “It’s called Mortensholm. We could anchor there, chill out, and stay there the night.”

Mortensholm turns out to be a beautiful sheltered little inlet surrounded by steep rock faces and forest. Three or four other boats are already in there, and there isn’t much room for us, particularly as there is a large shallow area in the middle we must avoid. We find a place between two other boats and drop anchor. But our swinging around the anchor brings us very close to one of them, and the occupant glares at us, his privacy disturbed and his boat in danger. A small Jack Russell bounds onto the deck and barks aggressively.

As a clever forestalling manoeuvre, the First Mate engages the man in conversation. She’s good at that. It turns out that he has worked in Africa, and knows Zambia well. We have an instant rapport, and the imminent collision is forgotten.

“I was working for a mining company there as an engineer”, he tells us. “Diamonds. We were looking for diamonds. I was in South Africa, Namibia and Zimbabwe too. Eight years in total, but in the end I decided to come back. There’s something about Norway that I like. I bought myself a boat and I spend the summers just exploring here and there. If I like a place I stay a bit longer; if I don’t, I just move on. Charlotte here keeps me company.”

Hearing her name, the Jack Russell wags her tail in agreement.

“It’s funny, isn’t it?”, says the First Mate to me later. “I haven’t thought about Zambia for years, but here we have been talking about it in the last two blogs.”

In the morning, we set off southwards along the Blindleia, passing through narrow gaps only a bit wider than the boat and only a few centimetres deeper than our draft.

We pass the small island of Småhølmene, the focus of a book we had both read over the winter called Island Summers, by Tilly Culme-Seymour. In it the author describes how her grandmother, a descendent the Norwegian shipping family, Olsen, buys the island just after WW2 in exchange for a mink coat, and, in true Norwegian fashion, builds a wooden cabin on it for summer holidays. She and her family then come every summer to escape their hectic, albeit somewhat privileged, lifestyle in England and enjoy the peace and freedom that their Norwegian island offers, a tradition that continues for at least three generations. It’s a charming enough story, at least the first part, giving a glimpse of relaxed Norwegian summers enjoying nature, fishing, swimming, sunbathing, cooking and eating. However, it seems to lose its way towards the end when the author and her boyfriend decide to stay the winter in the cottage, but in reality are there only from March to May, hardly the winter, even in Norway.

We continue to weave our way through the rocks and islands of the Blindleia, through tiny hamlets clinging to the banks on both sides, and eventually reach Mandal, the southern-most town in Norway, at the mouth of the Mandalselva River. Mandal built its wealth on the back of salmon fishing and timber trading in the 1700s, and still has a well-established, self-contented charm about it, with its white-painted wooden houses and beautiful golden-sanded beach.

We still have the infamous Lindesnes and Lista capes to negotiate. These two rocky headlands where the waters of the Baltic and the North Sea meet have been designated ‘Dangerous Sea Areas’ by the Norwegian authorities, as ferocious winds and high waves can build up suddenly, particularly from the predominant south-west. They are not to be taken lightly.

Luckily for us, the winds have gone round to the east, and are forecast to stay that way for several days. We need to make the most of them to go around the capes and as far as we can up the west coast before they turn.

In the morning, we set off from Mandal and head westwards, using only the genoa again and not the mainsail, due to the risk of the latter gybing. We had just heard a story of a boat the previous week which had gybed accidentally going around the Lindesnes due to a sudden change in wind direction, which had damaged its mast. Even with only the genoa out, we still make 7 knots, so we don’t complain.

In the event, we pass the Lindesnes and then the Lista without incident. The seas are choppy, but not dangerous.

“Well, that wasn’t too bad”, says the First Mate. “After all I read about them, I was a bit worried that it was going to be pretty rough. But that was tolerable.”

We stop for the night at the small island of Hitra, and its beautiful harbour of Kirkehamn, so named after its iconic white-painted church standing on a small promontory jutting out into the harbour. As luck would have it, there is a wedding in progress, and the small marina is full of the motorboats of the guests. We have no option but to tie up on the far side of the harbour against some old tyres with no facilities or power.

“It’s only for a night”, I say. “But we can walk around to the church and restaurant and have dinner there to make up for it.”

In the morning, the easterly winds are still favourable but are forecast to change in a couple of days, so we decide to leave at 0300 to make the most of them and to sail all the way to Tananger, a distance of more than 60 NM.

“The last few days have been quite long sails”, says the First Mate. “I’ll be quite glad when we get to Tananger, so that we can chill out a bit. But it is great that we have finally managed to get to the west coast of Norway in good time.”

We make it to Tananger in late afternoon. The wind is strong and it makes tying up to the jetty difficult, but there are several helping hands and soon we are secure.

On the way in, I had noticed that the VHF aerial on top of the mast was swinging from side to side, even though it still seemed to be working. The next morning, I send the drone up to have a look and take some photos, but it is still not clear what exactly has happened.

“My guess is that the retaining nut on the bottom has worked itself loose”, I tell the First Mate. “But it seems to be still attached at least. We’ll have to find someone who can go to the top and have a look at it. I’m too old for that sort of thing.”

I phone every boat repair company in Tananger, but none have free time to be able to do it as it is the start of the boating season in Norway. Eventually, I find someone north of Bergen who says that he can look at it.

“Bergen?”, says the First Mate. “But we won’t be there for at least two weeks. I hope that it stays on until then!”

So do I.