“I enjoyed the Munch museum yesterday”, says the First Mate, taking a bite from her sandwich. ”It was good to see The Scream at last. It gave me some inspiration for my own painting classes in the winter. I hope that I can remember it all.”

We are on the train to Gjørvik, two hours north of Oslo, to see our friends Ståle and Gunvor. Once clear of Oslo, we wend our way through deep valleys, lush forest, and fertile farms . It starts to rain heavily, the raindrops streaking the train windows. I reach for my coffee.

“Yes, he certainly taps into our deepest emotions of fear, anxiety and despair”, I say, recalling what I had read in the brochure we had been given. “All particularly relevant to today’s world. What I didn’t realise though was that he painted several versions of The Scream – I had imagined there was only one. And none of them are quite the same.”

“You certainly get the feeling that a lot of his work was based on his own personal experiences”, she says. “The early deaths of his mother and sister, and his own struggles with mental health, strongly influenced his depiction of illness, death and emotional turmoil. And the look of jealousy on the faces of the two women in Dance of Life. You could almost imagine that he, as the man, was enjoying it.”

We reach the station at Gjørvik. Ståle and Gunvor are there to meet us. We had first met them in Zambia in the late 1980s, when we had all arrived at the same time to work on various development projects – building roads, teaching, administration, agricultural research – coincidentally all funded by the Norwegian Government. We had somehow lost touch with each other over the years, but now that we are retired and have the time, it is nice to catch up with old friends again.

They look much the same as we remember them from 30 years ago.

“Well, apart from turning rather grey”, says Ståle. “And suffering the ignominy of new hair sprouting in senseless places!”

I know the feeling. Not to mention the teeth that have to be extracted, and the various aches and pains that seem to appear for no reason and take longer to disappear than they used to.

“Anyway, welcome to Norway”, he continues. “We have been preparing these last 1000 years for the retaliatory sea-raids out of Scotland after we did a little bit of looting and pillaging there. So we’ve been expecting you.”

Ståle is engaged in development and relief work as head of the Programme Department in an NGO in Gjørvik, while Gunvor processes building applications at the district municipality.

“We’ll pass my office on the way home”,Ståle says. “If you are interested, I can quickly show you around.”

We stop at a modern building not far from the centre of town. Inside, the walls are covered with posters of scenes in tropical countries and smiling happy people.

“It’s pretty much all funded by the Norwegian Government”, he says, as we tour the building. “Our work is on safeguarding children in developing countries, with particular focus on alcohol and substance abuse, mental health, children’s rights, and gender equality. We work through local partner organisations to support home-grown initiatives. A big part of what we do is to help with fund-raising for those initiatives.”

I ask him if he has any plans for retirement.

“There has been the odd hint that maybe I should start thinking about it”, he says. “But I haven’t risen to the bait yet. I love my job.”

We arrive at their house with a stunning view looking out over Lake Mjøsa, the largest lake in Norway.

“At 453 m depth, it is the fourth deepest lake in Europe”, Gunvor tells us. “In the winter, most of it can freeze over.”

“When I was young”, says Ståle, “I got my name in the local newspaper for ice-skating from one side to another. Unfortunately, I was seen as a reckless idiot rather than a hero. The thickness of the ice can vary considerably, and there is a real risk of falling through it. But I somehow survived to tell the tale.”

I shudder. The thought of being trapped under thick ice and not being able to find the entry hole before my breath runs out fills me with dread.

Over dinner, the conversation turns to economics.

“I’ve never really understood why everything is Norway is so expensive”, I say. “I suppose for Norwegians, though, you have the salaries to match, so things don’t seem so expensive to you? It’s only if you are coming from the outside that it does.”

“They were expensive because of the oil”, says Ståle. “We paid ourselves high salaries, even unskilled workers, because we could afford to. But actually now, salaries are levelling off so people are now starting to find things more expensive. It’s really only alcohol that is terribly expensive.”

“Yes, we are still trying to get to grips with the very strict rules that Norway has on the amount of alcohol you can bring in”, says the First Mate. “Do you think that it has any effect?”

“I know it is strange that we are so draconian now after the reputation the Vikings had for drinking”, says Ståle. “But I think that it’s helped to reduce a lot of family and social problems we used to have through alcohol abuse. Whenever they are asked, the public generally support the policy for that reason.”

We sleep that evening in a small cottage belonging to Gunvor’s niece, right by the shore of the lake. It’s idyllic. Particularly an early morning walk and watching the sun rise over the hills on the far side of the lake.

“I thought that we could drive to Lillehammer today”, says Ståle. “That’s where they hosted the Winter Olympics in 1994. There is an open-air museum there with a collection of houses from all over Norway and from different eras, which you might find interesting. Maihaugen, it is called. We can also have lunch there.”

After lunch in the museum restaurant, we find ourselves in front of an impressive-looking wooden church.

“It’s called a stave church”, a museum guide dressed as some sort of friar explains. “Due to its method of construction. Strong wooden posts rise vertically to give the structure strength, with lighter boards filling in the gaps between. The original church was built in the early 1200s in Garmo. It was dismantled in 1880 and transported here in 1921. The altarpiece and pulpit are both from the original church.”

Further on, we watch a woman making soap the traditional way.

“It’s amazing how you can mix fat and wood ash to come up with something that cleans”, says the First Mate.

“Did you see this house over here?”, calls Gunvor, pointing to a well-appointed, but distinctly suburban, house. “It’s Queen Sonya’s actual house. Don’t you remember that you met her in Zambia?”

There had been a royal visit by the then Crown Prince Harald and his wife Sonya to all the Norwegian-funded projects in Zambia. I had been asked to give a talk about the work that we were doing, and I distinctly remember standing in the middle of a field trying to explain to the royal entourage what agroforestry was all about. Later we had had lunch along with them, along with all the other Norwegians there. Sonya herself had been born a commoner, albeit a relatively well-to-do one, and the young couple were obviously very popular. More than a few tears were shed as they were taken to the small airport and their plane disappeared into the African skies towards Lusaka.

“The couple kept their courtship secret for nine years”, a panel in the house tells us. “In those days, royalty weren’t permitted to marry commoners. But Harald told his father that he wouldn’t marry anyone if he couldn’t marry her. Faced with the threat of his royal line dying out, his father agreed. Harald eventually ascended the throne in 1991 to become King Harald V of Norway, with Sonya becoming his queen.”

“She’s just repaying you for that interesting talk on agroforestry in Zambia you gave her in 1990 by inviting you into her childhood home”, jokes Ståle, taking a photo of me standing outside the house.

I am not so sure. I had always thought that I had bored them with my enthusiastic but technical talk of ecological farming. But who knows?

“I thought that we could drive over to our cottage west of here today”, says Gunvor the next morning. “Actually, my sister and myself inherited it when our father died, so we share it with them. They are there at the moment doing some tidying up work, so you’ll meet them.”

“We Norwegians love our cottages”, says Ståle. “They tend to stay in the family, passing from one generation to the next. Mostly they are quite basic with limited facilities, but offer a respite from the pressures of city life. I suppose it is all this getting back to nature thing. I actually have a cottage myself on the west coast on an island near Trondheim that I inherited from my father, although we hardly ever use it. We don’t even rent it out as it is more hassle than it is worth to find housekeepers and so on to look after it.”

It’s not all that different from the Cottage Country area in Ontario, Canada, where we had lived for a year, or, for that matter, the ‘bach’ culture in New Zealand, where I grew up. When we were children, my parents had had a small cottage at a local beach, which we visited from time to time in the summer. Happy memories of sunny days, playing in the sand on the beach, swimming in the small stream that flowed towards the sea, and, of course, eating ice-creams. Eventually we sold it, as us children grew up and moved away from home.

We drive up a winding, unsurfaced road, and arrive at a white-painted cottage in a large clearing in the forest. A ravine tumbles almost vertically from the mountain at the back, and an eclectic mix of agricultural implements lie next to a small shed.

“They’re Gunvor’s toys”, says Ståle, following my gaze. “Being an engineer by training, she loves mechanical things that can do serious work.”

Gunvor’s sister Sigrid and her husband Ragnor, along with their small dachshund, are already there. They are also both engineers, working on military projects.

“We are sailors too”, Ragnor tells us over a lunch of waffles. “We used to have a boat and sailed it in the Skagerrak a lot, both in Sweden and Norway. In fact , I have always been fascinated by the idea of travelling by wind power. In my younger days, a group of us kite-skied from the south to the north of Greenland. It was an amazing experience.”

I am suitably impressed. It had never occurred to me that such a thing was even possible, let alone achieved.

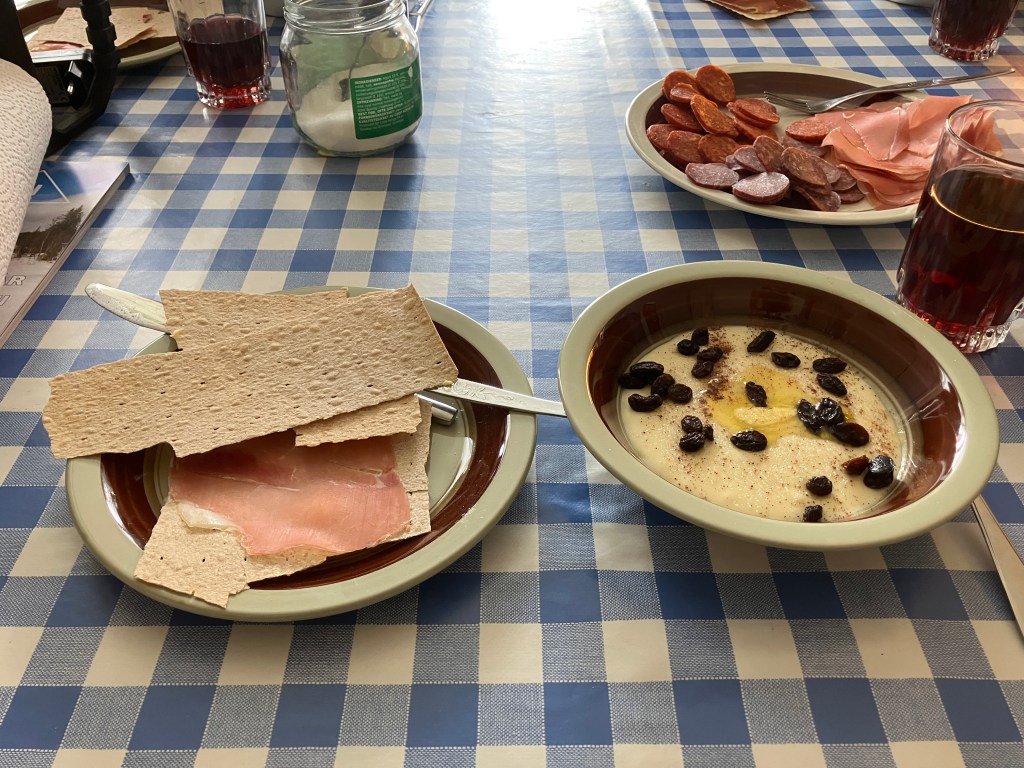

“Try some of this Rømmegrøt”, says Gunvor. “It’s a traditional Norwegian dish made with sour cream, milk, wheat flour, butter, and salt mixed into a kind of porridge. You can drizzle it with butter, and sprinkle sugar, cinnamon and sultanas on top. You normally eat it to accompany salami or ham and a flatbread. It’s quite rich.”

‘Quite’ is an understatement.

“Phew, that was absolutely delicious”, I say, after a second helping. “But I don’t think I can squeeze any more in without bursting.”

“Me neither”, says the First Mate. “I am going to have to diet for the next month.”

“When I was growing up, it was my absolute favourite dish”, says Ståle. “I couldn’t get enough.”

On the way back to Gjørvik, the conversation turns to our Zambian days.

“Do you remember that trip to Zimbabwe?”, asks Gunvor. “The time there was no flour in the whole of Zambia because the parts for the mill at Kabwe hadn’t arrived. We drove down to Harare to buy flour, a journey that took two days just to get there.”

“I do remember getting to the border at Victoria Falls on the way back”, I say. “What we didn’t realise was that there was a 10 kg limit on flour that you could take out of Zimbabwe. Most of it was confiscated by the border guards. I was heartbroken looking in the rear-view mirror at our precious flour bags piled up in a heap by the border post. Our whole trip was wasted.”

“You can be sure where that ended up”, says the First Mate. “I bet the border guards enjoyed their bread that night.”

The next day, it’s time to go. We need to catch the 0735 train from Gjøvik to Oslo to get back to Ruby Tuesday. The winds to make the 70 nautical mile Skagerrak crossing from Strömstad in Sweden to Risør in Norway are in our favour tomorrow, and we have to make the most of them of them or wait another week.

“We’ve really enjoyed our stay with you”, says the First Mate. “It was wonderful to catch up with you both again after all these years.”

“It’s somehow quite special, isn’t it”, says Ståle. “I mean, that four young people could meet in a remote corner in the deep interior of Africa, that this led to two marriages that still are intact and thriving after 35 years, that we could meet and exchange memories half a life later in the deep interior of Norway, and that we are as comfortable in each other’s company now as we were back then.”

I couldn’t have put it better myself.