“It’s only weed”, calls out a man on one of the boats tied up to the quay. “You’ll be able to push through it no problem.”

We have just arrived in the small harbour of Kristianopel, and are negotiating the entrance. The depth sounder has just told me that the depth under the keel is zero, meaning we are grounded. But it doesn’t feel like it and we are still moving slowly.

I ease the throttle forward and sure enough we keep going. No graunching sound of cast iron against rock, or even squelching against mud for that matter. On either side, we see the stringy tendrils of aquatic plants rising to the surface. Suddenly we have 0.6 m water clearance. Plenty! We tie up alongside our helpful advisor.

“We thought the same when we came in”, he says as he takes our lines. “We were almost going to anchor outside the harbour, but someone told us it was just weed. It’s only at the entrance.”

We boil the kettle and take stock. Kristianopel’s claim to fame is that it once was a fortress town on the border between Denmark and Sweden in the days when Denmark was a major power and included much of southern Sweden. The Swedes weren’t particularly happy about this arrangement and mounted a series of attacks across the border. The Danish king, Christian IV, became fed up with all this aggression, and in 1606 decided to build a fortress to defend against these attacks.

“He named it after his baby son, Kristian”, says the First Mate, reading the guide book. “But added a ‘-opel’ to the end to make it sound a bit more sophisticated, like Constantinople.”

The fortress didn’t help matters for the Danes all that much, as only a few years later in 1611, the Swedish captured it and burnt it to the ground and destroyed the church. The Danish retaliated and the fortress changed hands several times over the next few years, but eventually the Danes were so exhausted that they sued for peace.

We go ashore and explore the village.

“What a pretty little place”, says the First Mate. “It reminds me of the cute villages that we saw when we explored southern Denmark a few years ago.”

The fortress walls still exist in most places, and we walk along them trying to imagine life behind them in those days rather than the caravan park that it is nowadays. The occasional cannon pointing northwards towards Sweden and an ancient brazier for showing ships the way into the harbour help a little.

“I read that the peace treaty was signed just north of here”, I say. “At a place called Brömsebro in 1645. There’s a memorial stone there. We could cycle up there tomorrow and have a look at it. There’s a smokery where we could have lunch.”

“Look, there’s a dual flag combining the Swedish and Danish flags”, exclaims the First Mate, pointing to a flagpole outside one of the houses. “I suppose you could take it to mean that Sweden and Denmark are now friends with each other.”

“Or that the owners still can’t make up their mind whether they are Swedish or Danish”, I say. “So they hedge their bets!”

In the morning, we unload the bikes and cycle up to Brömsebro. It takes a bit to find the Peace Stone, but eventually we do, nestled in a small grove by a brook that used to demarcate the border between Sweden and Denmark.

“It’s not a very impressive border”, sniffs the First Mate. “You would have thought that they had chosen a river or something that could have been more easily defended. Look, I can jump from one side to the other.”

The words on the stone say ‘In memory of the peace in Brömsebro. De la Thuliere – Axel Oxenstierna – Corfitz Ulfeldt. The stone was raised in 1915.’

“It says in the guide book that the treaty was mediated by France”, I say. “De la Thuliere was the French ambassador, Axel Oxenstierna was the Swedish representative, and Corfitz Ulfeldt was the Danish representative. It was a big deal for Sweden, as the terms of the treaty now exempted its ships and traders from paying tolls to the Danes if they were passing through Danish territory, and they also added Gotland and the island of Øsel in modern day Estonia to Swedish territory. It marked the decline of Denmark and the start of the rise of Sweden as a Great Power in the Baltic.”

“I am always intrigued how empires come and go”, says the First Mate. “They always seem to overreach themselves and then can’t hold on to their territory.”

In the evening, we sit in the cockpit sipping our wine, and watch the swans and their young ones swimming serenely near the rocks just outside the harbour entrance.

“Something seems to be disturbing them “, says the First Mate suddenly. “Look, I think that it must be that big bird that has just landed on the rocks.”

“It looks like a golden eagle”, I say, looking through the binoculars. “No wonder the swans are upset. Golden eagles will eat the cygnets. It’s probably just waiting for its chance to grab one.”

The swans swim agitatedly towards the safety of the harbour, the little ones following their anxious parents. The golden eagle remains nonchalantly on the rock eying a cormorant, then flaps lazily off.

Strong winds are forecast for tomorrow afternoon. We decide to try and reach the next small harbour, Sandhamn, before they start.

“Look!”, says the First Mate as we arrive. “Klaus & Claudia are here. I can see their boat Saare. And there is a space behind them where we can tie up.”

“We’ve been here a couple of days”, Claudia tells us. “After we left you in Stora Rör, we went to Kalmar, hired a car for a day, and explored Öland. After that, we sailed down here.”

“It’s quite sheltered here from the west”, says Klaus. “And we are on the right side of the pontoon. We should be blown off it with no screeching of the fenders rubbing all night long.”

—-

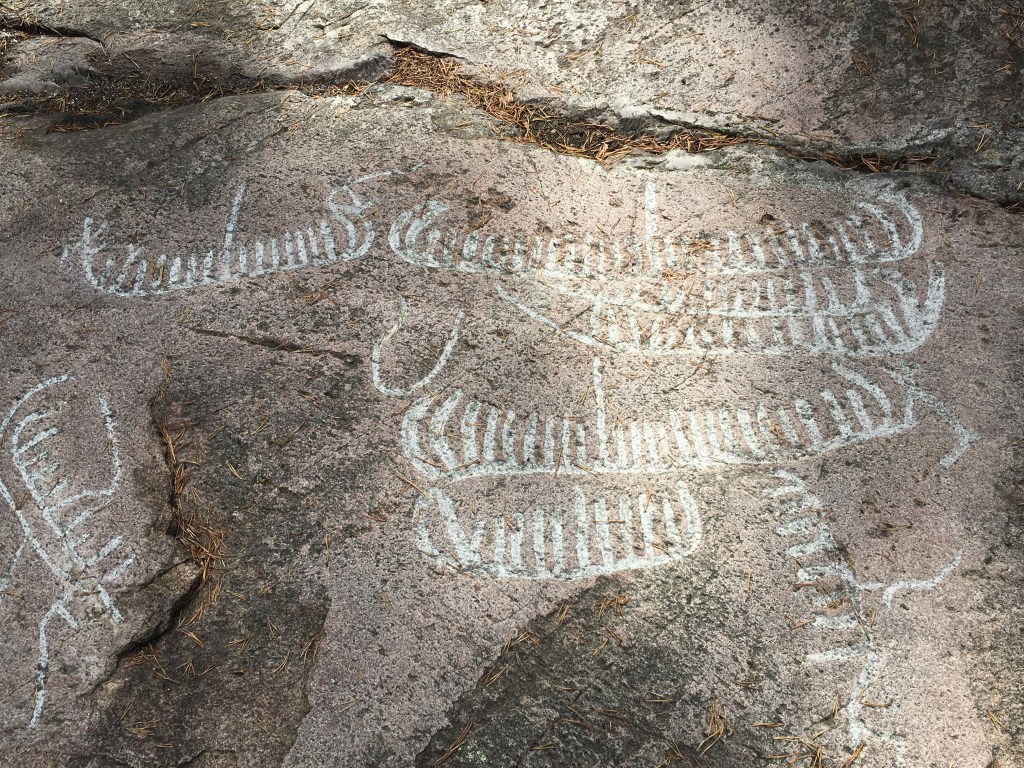

The shaman chants an ancient prayer to the spirit of the forest and guides the boy’s forefinger around the horse shape carved into the rock.

“The spirits are pleased with you”, whispers the shaman. ”Don’t resist them. Breathe deeply and allow their power to take over your being. You will be a great horseman and will protect your people against the enemies that will come. Just like your father before you.”

The boy feels the power of the animal surge through him, filling him with awe and connecting him to the OtherWorld, the land of his ancestors.

“Now, you must make your own picture”, says the shaman, giving him the metal tool he has been carrying. “For those who follow after you to gain strength from. As those that have gone before you have done. Let the spirits guide you to release the shape that is within the rock.”

The boy hesitates only for a moment, but he knows exactly what he will draw. As the wind sighs gently through the pines, he begins to slowly and deliberately scratch at the rock with the tool until a shallow groove appears. His face furrowed in concentration, he continues his work throughout the afternoon until the light begins to fail. His back aching from the unnatural position he had taken to carve his picture on the rock, he stands up.

“I’ve finished”, he says.

Together they take in his creation.

“It’s Sol”, says the boy. “The giver and sustainer of life to us. I want her to look favourably on our people, and ensure that our crops grow, that our animals flourish, and that the forest remains our provider.”

“You have drawn wisely”, says the shaman. “Thousands of years hence, people will look at these pictures and mourn the loss of the ties to the spirit world that we have.”

“Did you see the carvings of the ships?”, says a familiar voice. The mists of time dissolve in a flash.

It’s the First Mate. We are visiting the Bronze Age petroglyphs at Hällristningar på Hästhallen, just to the north of Sandhamn. We had cycled out with Klaus & Claudia after lunch, turned off the main road and walked to the rock outcrop in a small clearing. We had spent the last half-an-hour or so marvelling at the 140 carvings of ships, horses and riders, deer, sun wheels, soles of feet, and cup marks. I am imagining how they might have come to be there.

Dated to around 1000 BC, the figures portray religious rituals and aspects of daily life in Bronze Age Scandinavia. When the rock carvings were made, the area was the coastline; but it is now 25 meters above sea level.

Back at Sandhamn harbour, I see that another boat has arrived and has tied up on the other side of the pier to us. What’s more, it is flying a New Zealand flag.

“You’ve come a long way”, I say to the couple sitting in the cockpit.

“Well, we have just come from Germany where we have bought the boat”, the man says. “So not too far. But we are going to sail it back to New Zealand in a couple of years’ time after we explore Europe. My name is Ian, by the way, and this is Colleen.”

When they hear that I am also from New Zealand, they invite us aboard for a drink. It turns out that Ian is the son of a university lecturer who taught me when I was at university. It’s a small world!

The winds die down over night, and the next morning we sail for Utklippan, a remote group of three tiny islands off the south-east corner of Sweden. Stunningly beautiful, these islands are the site of a lighthouse built in the 1800s. The lighthouse was deactivated in 2008, deemed not to be useful for modern day shipping. The islands are now a Nature 2000 reserve, famed for their wildlife. The rectangular guest harbour has been cut out of the rock of the northern-most island, and is a popular stopping-off place for sailors.

When we arrive, Klaus and Claudia are already there. They are the only ones.

“I’ve never seen it so quiet”, says Klaus. “It’s usually much busier than this. I have seen boats rafted up three or four deep sometimes.”

In the late afternoon, a black RIB arrives and ties up just in front of us. In it are two people in uniform.

“We are the coastguard”, one tells us. “We see that your boat is from the UK. Can you show us your passports, please?”

I disappear below and manage to locate our passports and other permits. They show little interest in the First Mate’s German passport, but study my NZ passport intently. We had arrived in Sweden in April, but my Swedish Visitor’s Permit allows me to stay for six months from then, longer than the Schengen visa waiver of three months. Satisfied, they glance around cursorily, jump back in the black RIB, and are gone.

“It’s interesting that the Finns seemed to be more interested in whether the boat had had VAT paid on it, whereas here in Sweden, they are more concerned about our passports”, says the First Mate.

In the evening, we decide to have a joint dinner with Klaus & Claudia. They bring a lamb curry and rice, while we do a vegetable curry.

Over dinner, the conversation turns to the upcoming elections in Thuringia and Saxony in Germany.

“All the indications are that the far-right Alternative for Deutschland (AfD) party will do well”, says Klaus. “There is real concern in Germany that this could lead to a return to the Nazism of the 1930s if they receive too much support.”

“We grew up having Nie weider, never again, drummed into us”, explains the First Mate. “So it is a bit of a shock when so many people support a far-right party.”

“It’s interesting that the AfD wasn’t always far-right”, says Claudia. “It was actually started in 2013 by a group of economists protesting against the bailouts to the southern Europe countries during the Eurozone crisis. They wanted these countries to leave the EU. It was only later that the party evolved towards the far-right when its various leaders jumped on the immigration bandwagon in an effort to gain votes.”

“It has its strongest support in the former Communist East Germany”, says Klaus. “But what is worrying is that a large number of young people, whom we expected to be progressive, support it too.”

After Klaus & Claudia have gone, I sit in the cockpit musing over what we had been talking about. Surely Nazism won’t reappear?

“I overheard your conversation”, says Spencer from his home in the canopy. “It’s interesting, as I was just reading the other day that the AfD won’t gain power as it is just an East German thing. You see, West and East Germans are very different people, and the differences go much further back than the Communist era. Right back to our old friends, the Teutonic Knights, in fact. It was because of them, and those that followed them, that the Baltic Germans developed a colonial mindset where they dominated the indigenous Balts and Slavs. When Hitler recalled them just before WW2, most relocated to eastern Germany, bringing their conservative right-wing worldviews with them. These views largely remain today, despite 50 years of Communist rule. So the AfD has a lot of support in the east, but it won’t gain much ground in the more liberal west.”

“Well, I hope you are right”, I say doubtfully. “But my concern is that too much immigration touches a raw nerve in both east and west Germany, which the AfD plays on. We’ll just have to see how it pans out.”

In the morning, as I drink my first tea of the day and do the crossword, there is a sound of voices outside. I poke my head out to see what is going on.

“We have come from the mainland to empty the rubbish bins”, says one of the voices. “I hope we didn’t wake you up?”

“How do you know when to come?”, I ask. “They might be empty and it would be a wasted journey.”

“Ah, but the bins are intelligent, you see”, he answers. “After someone has deposited something in there, it triggers a press and the rubbish inside is compressed. When the bin gets to around 80% full of compressed rubbish, it sends an email to our headquarters to tell us that it is nearly full. We then jump in a boat and come out to empty it. That way, the bins never overflow, and we don’t have any wasted trips. It’s all powered by this solar panel on top, see.”

After breakfast, we clamber into one of the small rowing boats provided on each island, and row over to the other island to explore the remains of the lighthouse station.

Suddenly there is a massive series of thumps that reverberate throughout the island.

“What on earth was that?”, shouts the First Mate in alarm. “Did something fall down?”

“It sounds like heavy guns firing”, I say. “Perhaps the navy are practising.”

Sure enough, in the haze of the horizon we see a warship firing its guns, puffs of smoke being carried away by the wind.

“Crump … crump … crump”, go the guns. Then a few seconds later, another “Crump … crump … crump” in response, this time not quite so loud.

“There’s another ship that must be below the horizon”, I say. “We can’t see it.”

“I hope that they are only practising”, says the First Mate. “But what if the Russians have invaded Poland and this is the beginning of WW3? What would we do?”

“I suppose we could try defending the island with that cannon ever there”, I say doubtfully. “We might be able to hold them off for a minute or two, if we are lucky.”