We leave Timmendorf at 0800. The wind is from the south-west, but it is only a few knots, and we move slowly. We follow the buoyed channel through the shallows to the north of Poel Island, and eventually emerge into deeper water.

The wind is now directly behind us, so we ‘goose-wing’ with the genoa poled out to one side and the mainsail rigged with a preventer to guard against an accidental gybe. We round the Trollegrund Spit, and with the wind now more on our starboard, we have a nice broad reach sail along the coast.

“This is my type of sailing”, says the First Mate, going down to make tea. “At least we don’t have to worry about things flying around everywhere.”

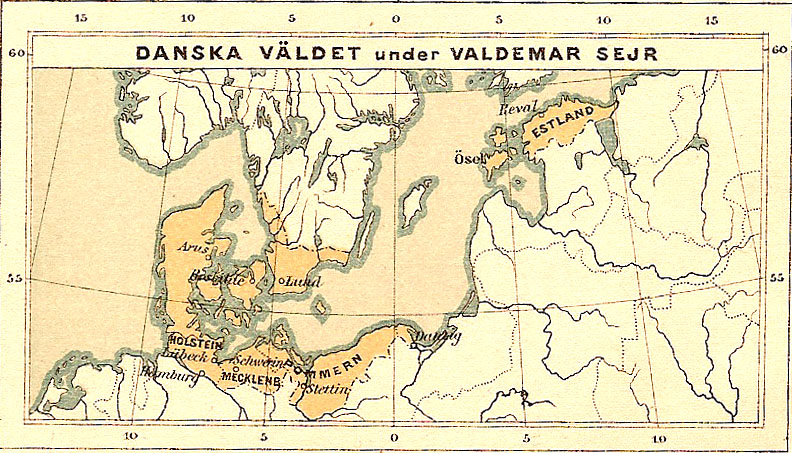

My mind turns to the book I am reading at the moment, Can Democracy Work? A Short History of a Radical Idea from Ancient Athens to Our World, by James Miller. In it he describes the development of democracy, from its first airing in ancient Athens, then much later the French Revolution espousing freedom and equality, the American Revolution, the Russian Revolution, through to modern liberal democracy. For a long stretch of history, democracy was thought to be an inferior form of government, and a monarch and aristocratic hierarchy much better with every one knowing their place.

“All very interesting”, says Spencer, from the coaming behind me. “But the big drawback with democracy is that most people don’t have time to practice it directly – they are far too busy making a living, raising a family, developing careers, saving for their retirement, and so on. Therefore, they elect representatives to do their democracy for them.”

“Well, well, well”, I say. “Nice to see you. How was the winter?”

“Great”, he responds. “It was nice and warm in the anchor locker, but I thought I needed to get out and stretch my legs now.”

He stretches each one in turn. It takes quite a while.

“Anyway, as I was saying”, he continues, “The danger is that these representatives become a new elite – they do what they want for the duration of their terms, make lots of money from themselves and their friends, control the media to influence the way people think about them, and get themselves re-elected. And so it goes on. Over time, these representatives get richer and more powerful, make laws for the small people but not themselves, and before you know it you have a new elite. Then the small people may get fed up and decide to have a revolution to make people more equal, and the whole cycle starts again. Democracy is an inherently unstable system that contains the seeds of its own destruction.”

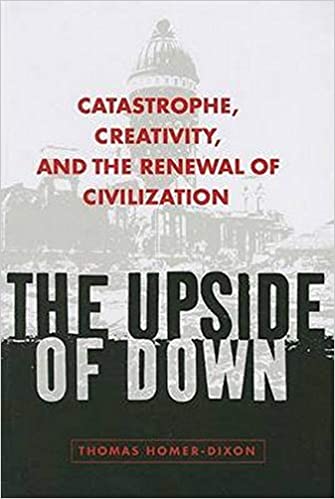

“That all sounds a bit nihilistic”, I say. “Here was me thinking that the human race progresses, rather than going round and round in circles. I remember reading a book called The End of History and the Last Man, by Francis Fukuyama, in which he argues that modern liberal democracies are the pinnacle of human political organisation.”

“Complete cobblers!”, says Spencer. “I’ve read it too. He comes up with this idea that the human psyche is composed of three parts – basic animal desires for food and shelter, intellectual reason, and the desire to be recognised as a human being of some worth. He then manages to deduce somehow that only liberal democracies provide satisfaction of all three desires, particularly the third one. Once a society gets to be a liberal democracy, there is no driving force left for it to develop any further politically as all its citizens are free to develop to their potential and be someone of worth.”

“It sounds like there could be something in it”, I say.

“No, it is all about power”, he responds. “Trying to gain it, then trying to keep it. Nothing else explains the flow of human history. The political systems that you come up with are just expendible structures that you build for certain elements of your societies to maintain power. Look at what is happening in America at the moment with the storming of Capitol Hill, preventing peaceful transition of power, voter suppression, gerrymandering and so on. And the UK is not much better, with its prorogation of Parliament, Downing Street parties and the like. The elite don’t give a hoot about democracy as such, it’s all about maintaining their power.”

We are approaching Warnemünde, and I need to concentrate. We break off the conversation. The First Mate appears.

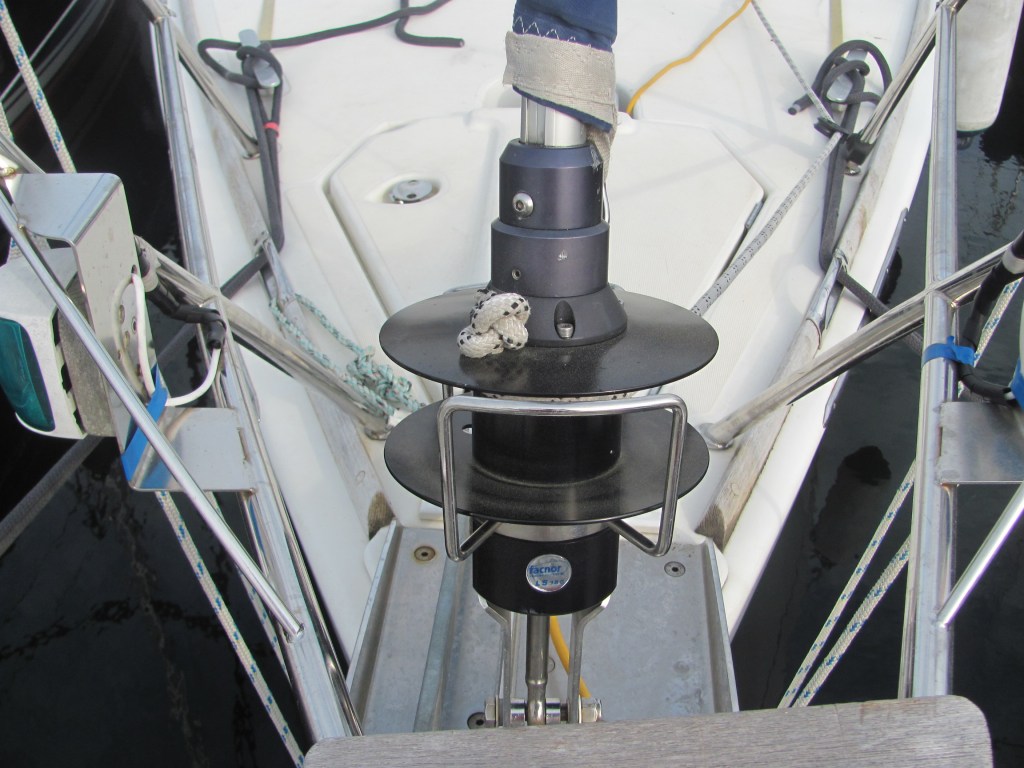

“Look at that weird ship”, she shouts, as we approach the entrance to the harbour. “It looks like it has a huge funnel on it. I wonder what that is for?”

“Ah, I was reading about that last night in those brochures you got”, I say. “It’s a rotor sail. It works by rotating and creating lower pressure on the front side of it and higher pressure on the stern side, a bit like a sail. The difference in pressure helps to pull the ship along and reduce fuel consumption. It’s made by a company called NorsePower and has been fitted to some of the ferries between Germany and Denmark.”

“That’s very clever”, says the First Mate. “I wonder why more ships don’t have it?”

“It’s a help”, I say. “But the problem is that it really only works when the wind is blowing at right angles to the direction of travel. It works well here in the Baltic as many ferry journeys are north-south and the predominant wind direction is west-east. They claim it reduces fuel consumption by between 5 and 20%.”

“That’s worth having”, says the First Mate. “But why don’t they just put giant sails on the ferries and be done with it? They could have them computer-controlled to adjust them to the right angle.”

It’s a good question.

We furl our own sails and motor the last little bit into Warnemünde. We have decided to stay in the Alter Strom, the old harbour near the town centre, if there is space, rather than in the brand new spanking marina on the eastern bank. There is something attractive about being near a city centre and being able to watch life going by rather than in a parking lot for boats that most marinas seem to be. The only thing is that we have to tie up against piles where fenders don’t work properly, so we need to use our boards.

As we arrive, out of the corner of my eye I spot a British flag on one of the boats already tied up. Later, we are invited for a cup of tea with the owners, Jim and Marjorie. It turns out they are also from Scotland, from Inverness, not all that far from us.

“We saw your Scottish flag, and wondered if you were from there”, says Marjorie. “You don’t see many boats from the UK these days, let alone from Scotland.”

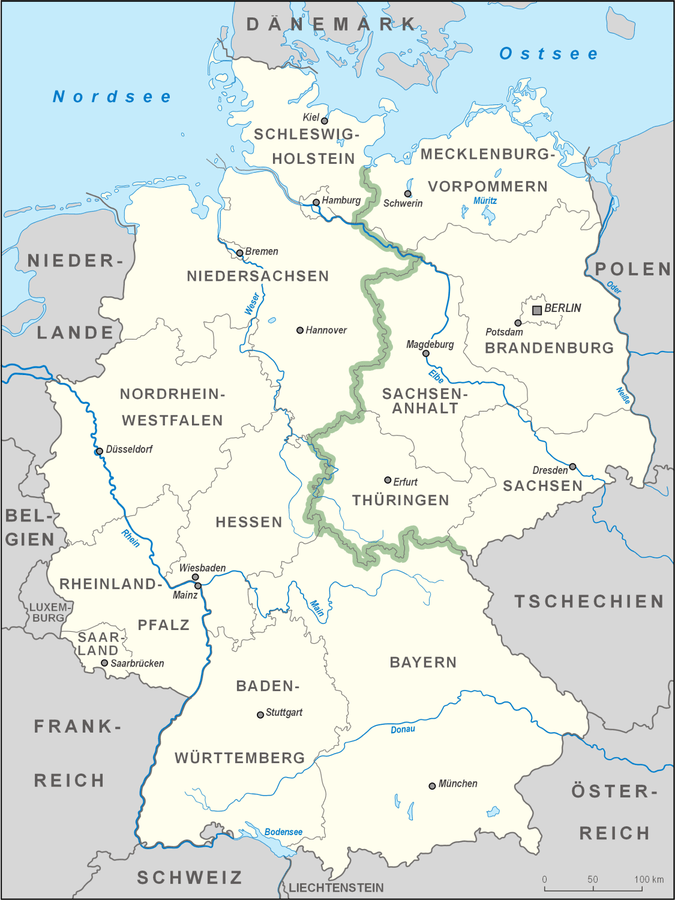

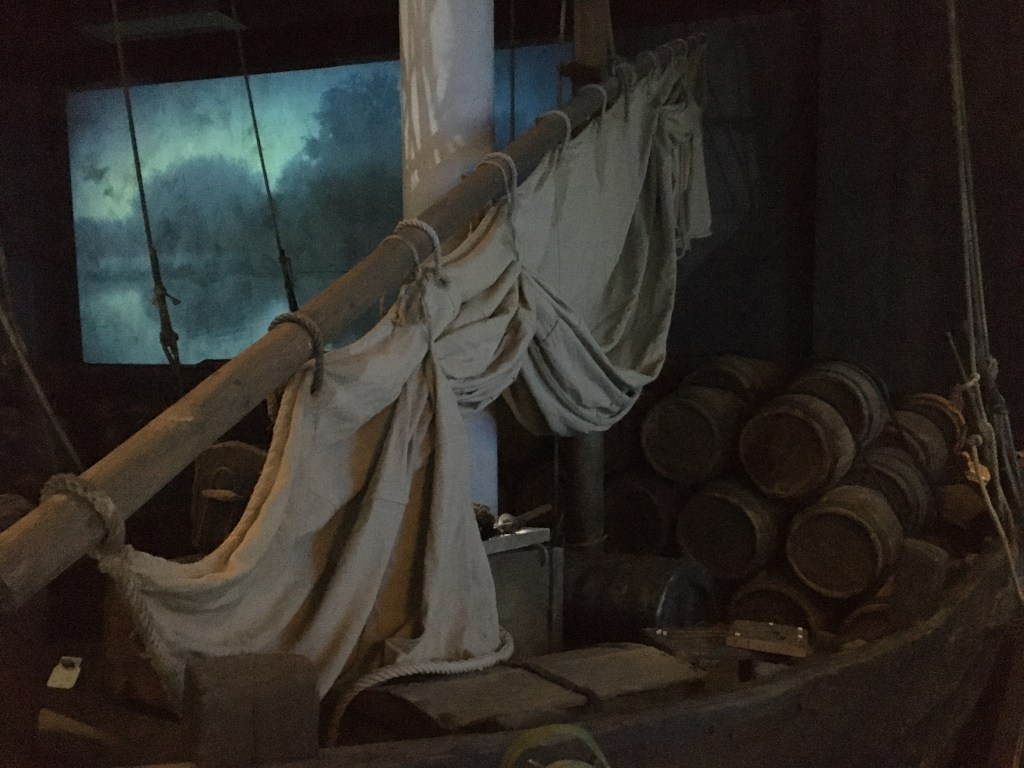

When they retired, they bought an old wooden motor boat, did her up, and now they are exploring the waterways of Europe. They have a relatively shallow draft, so are able to tackle most of the rivers and canals. They had overwintered their boat on Fehmarn, and were heading into the canal system at Rostock.

“The problem we have at the moment is that she dried out over the winter”, says Jim. “She was in a shed, but was near the corrugated iron wall, and when the sun shone, it would heat the air inside quite a bit. The wood has contracted, and even though we have been back in the water for about a month now, it still hasn’t expanded back again completely and is still leaking a lot.”

“And that’s not all”, says Marjorie. “The bilge pump is playing up too. The float switch gets stuck and sometimes won’t turn either on or off again. But if we give it a tap with a stick, it seems to free it up. In fact, if you will excuse me, it’s time to tap it again. I’ll be back in a minute.”

She disappears down below. We hear some tapping, and a pump motor starts somewhere. I look around for the lifejackets, and drink my tea a bit faster.

“Don’t worry”, says Jim. “She’ll be OK in a couple of weeks once the wood has expanded again. The boat, that is.”

I am not sure I want to stretch my tea out that long, but I have to say that I admire their sang froid. To be travelling around Europe in a leaky boat with a dodgy bilge pump is not everyone’s cup of tea, so to speak.

As we leave, I notice a steady stream of water coming out of one of the outlets on the side of the boat. The pump is doing its job at the moment, I think.

In the morning, we explore Warnemünde. The town was originally a fishing village, but developed as the seaside resort town of Rostock in the 19th century, and nowadays is an important harbour for the cruise industry. Expensive shops and restaurants line the other side of the Alter Strom from where we are tied up, while floating fast-food cafes offer quick snacks of fischbrötchen, fisch and schipps, and filled rolls. A paddle steamer splashes past.

We eventually arrive at the lighthouse. Built in 1897, it is still in use, and for €2 even allows tourists to climb the narrow stone stairs 37 m to the platform near the top. The view from the top over the Baltic Sea to the north and the town to the south is superb.

At its base is the so-called Teepott restaurant, rebuilt from an earlier building destroyed by fire in the 1960s in GDR days.

“Why do you think they called it the Teepott?”, I ask. “It doesn’t look much like a teapot. I can’t see either a spout or a handle.”

“There is a passing resemblance to one of those tea cosies that you use to keep the teapot warm”, says the First Mate. “Perhaps that’s the reason. The curved roof is supposed to be a good example of East German architecture, by the way.”

West of the lighthouse and the Teepott stretches the long sandy beach and its ubiquitous strandkörbe that makes the town attractive as a resort.

In another street, we come across the Edvard Munch house, a former fisherman’s cottage. Seeking peace and quiet, the Norwegian painter of The Scream had come to Warnemünde in 1907 to escape his demons, and had painted and sketched many scenes in the area. However, despite being well-liked by the inhabitants, he abruptly left without reason only 18 months later, never to return.

“We have to go and see Rostock while we are here”, says the First Mate over breakfast the next morning. “Apparently you can get the train down there for a day. It’s only about five minutes’ walk to the station from here.”

We catch the S-Bahn to Holbein Platz on the outskirts of Rostok and change to the Straßenbahn to reach the city centre. We get off at the Kröpeliner Tor, the westernmost gate of the old centre.

From there, we wander along the old city walls, passing the Kloster St Katharinen, a former Franciscan monastery. Now it is the Academy of Music and Theatre in Rostock.

“It’s certainly very peaceful in here”, says the First Mate as we wait for a group of school pupils to take photos of each other against the buildings. “I think I wouldn’t have minded being a monk in those days.”

We eventually reach the Universitätsplatz in front of the imposing University main buildings.

“Very impressive”, says the First Mate.

“What on earth do you think is going on here?”, I ask further on. “I am not sure my delicate constitution can cope with this.”

We are standing in front of a series of nude sculptures clustered around a fountain in the centre of the square.

“It says it is called Brunnen der Lebensfreude”, says the First Mate. “The Fountain of the Zest for Life. But apparently the locals call it Pornobrunnen. I am not sure why.”

“I think I can guess”, I say, as I try and work out which limb belongs to whom in a writhing couple. The two dogs expressing their love for each other ignore me.

We wander down Kröpelinerstrasse until we come to the Neuer Marktplatz in front of the Rathaus, the Town Hall. In the centre is the Möwenbrunnen, a sculpture of a seagull surrounded by Poseidon, Triton, Nereus, and Proteus, four Greek gods of the sea. A market is in progress, so we have a little browse.

On the other side of the square are picturesque houses of wealthy Hanseatic merchants.

Just off the Neuer Marktplatz is the Marienkirche, a massive structure in North German Gothic brick style.

“We’d better go and see this one”, says the First Mate. “There is supposed to be an astronomical clock in it. Apparently it still works. You’ll probably want to see that.”

“Did you know that senior citizens can have a 30% reduction?”, says the lady at the ticket desk.

I don’t know whether to be pleased to have the reduction, or to be annoyed at being identified as a senior citizen. I decide on the former. The latter is reality I suppose.

We find the astronomical clock at the rear of the church. Apparently it still has all its original clockwork and has not stopped working since it was built in 1472, being wound every day and greased regularly down through the ages.

It’s a thing of beauty. I stand for a time in front of it, taking in its intricacies and the peculiar mix of religion and science in its construction. Not only does it give the time, but also the phases of the moon and the solar year. Apparently at noon each day the twelve apostles rotate around to obtain God’s blessing in turn – I glance at my watch, but unfortunately we have missed that.

It is fascinating to think that it was built around the beginning of the modern scientific revolution, just as people were starting to realise that the world wasn’t just a series of random occurrences caused by the whim of some capricious god or gods, but instead ran according to well-defined rules that could be used to predict the future. The dawn of the modern mind.

“It’s pretty amazing, isn’t it?”, says the lady at the ticket desk on the way out. “When it was built, Christopher Columbus hadn’t even discovered America. Where are you from?”

We tell her.

“Ah, my brother is over in Scotland at the moment”, she says. “He’s sailing as well. He’s trying to retrace some of the voyages of St Brendan the Navigator on the west coast of Scotland. Sort of a pilgrimage. Just last week he was on Eileach nan Naoimh.”

“The Island of the Saint”, I say. “Where Brendan set up a monastery. Reputed to be the mysterious Hinba, where Columba came from his monastery on Iona to contemplate. We’ve been there too.”

We had anchored in the small bay of Eileach nan Naoimh, the southernmost of the Garvellachs in the Inner Hebrides, a few years ago when we had been exploring the west coast. Although we had not gone ashore, we could see the small beehive huts and the other monastic buildings that the monks had constructed on the lonely, windswept island.

We chat for a few minutes on St Brendan, sailing, and how we come to be in Rostock.

“Amazing”, says the First Mate, as we leave. “Fancy coming across a connection with an island in Scotland while in a medieval church in Germany.”

That evening, we huddle inside Ruby Tuesday as a thunderstorm rages around us.

“Wow, that one was close”, says the First Mate. “It must have been just overhead. I just hope that we are not the tallest mast here.”