“Look, there’s a naked man who has just dived into the water over there”, says the First Mate, pointing to the shore at the end of the bay. “And a woman.”

“They have probably just been in a sauna and are cooling off”, I say.

We are in a small inlet on the island of Skedöfladen, surrounded by forest with the occasional cabin here and there hidden behind the trees. We had left Hanko in the morning, sailing eastwards, and had decided to stop there overnight. Dropping the anchor at the top of the inlet, we had relaxed in the warm sunshine sipping wine, listening to the chorus of birdsong coming from the forest and watching the grebes diving amongst the reeds on the shore, the black-headed gulls wheeling overhead, and the solitary heron on the rock at the end of the bay.

“It’s so peaceful here”, says the First Mate dreamily, pouring her second glass of wine. “So close to nature. I can understand why all the Finns want to escape to their cabins in the summer time. It’s a spiritual thing.”

She loves her broad generalisations. But she has a point.

“I think that I can relate to that”, I say. “I wouldn’t mind spending a summer in a place like this. Just reading, thinking and writing, and a small boat to go fishing. Very inspirational.”

The naked couple climb out of the water onto the small jetty and walk unashamedly back into the trees.

“I read somewhere that there was a some opposition to boats being able to freely anchor in Finland when they were drafting their Jokaisenoikeudet, or Everyman’s Rights”, says the First Mate. “Because of people wanting to swim after having a sauna in their summer cabins. But this couple don’t seem to be bothered. They must be aware we are here.”

“The rules says that you mustn’t anchor close to private plots”, I say. “Although they leave the definition of how close ‘close’ is to common sense. I think we are far enough away.”

The next morning it is raining. We wait until lunchtime until it stops and the wind changes, then we carry on. In the late afternoon, we reach Barösund, a small harbour in the narrow sound between the islands of Barölandet and Orslandet. We tie up and go to explore.

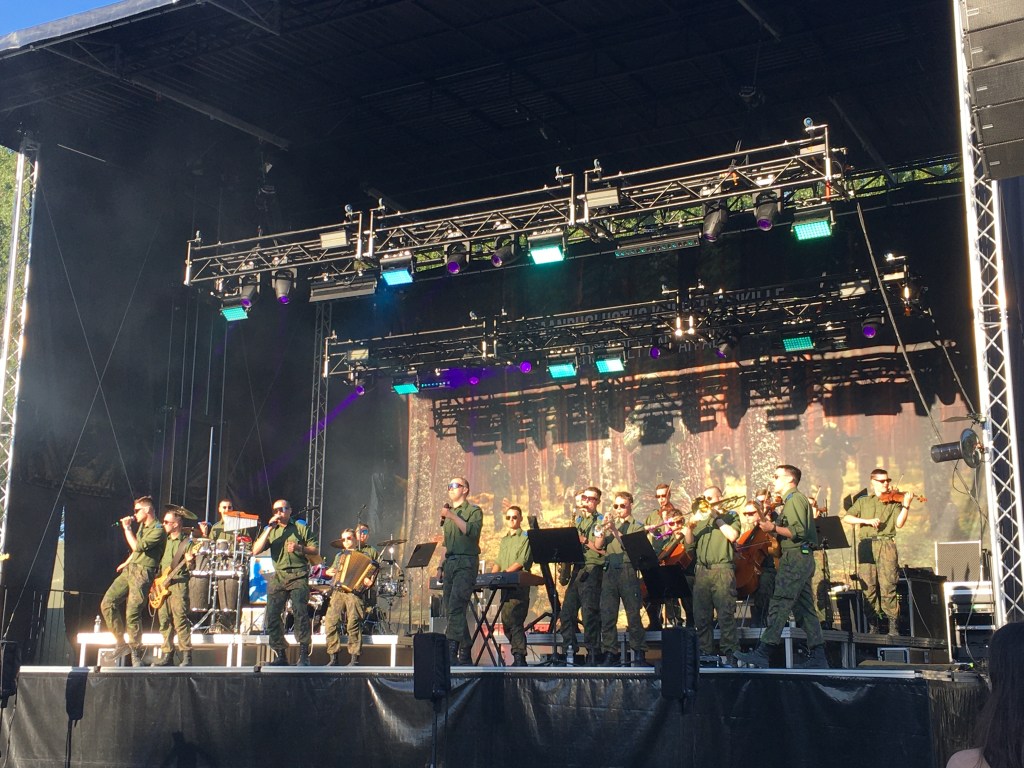

“Look over there”, shouts the First Mate, pointing to two boats coming up the sound. “One boat is being towed. I think it’s the same one that we saw heading out when we were coming in. I recognise the sign on it – ‘Skärgärdsteatern’. Maybe they have broken down.”

Sure enough, the first boat turns out to be the coastguard, and there is a line back to the second, some sort of trawler. We had seen it earlier in the day. They reach the harbour and make a slow circle around so that the trawler is facing the quay. A second coastguard boat moves behind and gently nudges the trawler alongside the quay. They seem to know what they are doing.

A small crowd of people has gathered on the quay to watch the spectacle.

“Look out”, someone shouts. “They’re going to hit the pole. Someone do something.”

Sure enough, as the trawler comes alongside, a dinghy suspended on davits that protrude beyond its beam catches a pole with a life-ring and defibrillator on it. Being closest, I try to push the dinghy up out of the way, but I am too late. The pole snaps off at the base. The trawler gradually comes to a stop and is made fast to the quay.

“We are a theatre group from Helsinki”, explains one of the girls sitting at the bow. “We are on our way to Hanko to give a performance. We thought it would be cool to go by sea. But about an hour after we left Barösund, thick white smoke started coming from the engine. We were just thinking of going down to have a look when it stopped completely. Luckily we were in mobile range, so we called the coastguard and they came and towed us back.”

“What about your performance in Hanko?”, asks the First Mate. “Won’t you miss it?”

“Luckily it isn’t until the day after tomorrow”, she says. “We’ll just have to try and get a bus or something there. There should be enough time.”

“Quite a drama”, I say to the First Mate as we walk back to the boat.

We push on eastwards the next morning. Soon the skyline of Helsinki appears on the horizon and we make our way through the dozens of small islands and rocks that guard the entrance to the city, keeping a vigilant lookout for the many ferries and cruise ships coming and going.

We eventually tie up at the Helsingin Moottorivenekerho marina with the spires of the Eastern Orthodox Uspenski Cathedral towering over us.

“Look at the way the sunlight is reflecting off those onion domes”, says the First Mate. “Let’s go over in the morning and have a look inside it.”

In the morning we unload the bikes and cycle over. Inside, it is as sumptuous as it is outside. Commissioned by Tsar Alexander II of Russia, it was completed in 1868. I am surprised to learn that many of the bricks used in its building were ferried from the fort at Bomarsund in the Åland islands that we had visited last year.

“Apparently two of the icons were stolen”, says the First Mate. “One was stolen in 2007 in broad daylight at lunchtime with dozens of tourists present. They still haven’t got it back yet. The other was stolen in 2010 in a break-in, which they did recover eventually.”

The Lutheran Cathedral is a little bit further on, in Senate Square. Completed in 1852, it was originally built as a tribute to the Russian Tsar, Nicholas I. True to Lutheran philosophy, it is a lot less ornate than the Eastern Orthodox cathedral.

Continuing, we find the Temppeliaukio church, carved out of solid rock, with its translucent skylight and copper dome.

“Apparently, the acoustics of the rock are so good, they hire it out for music concerts”, says the First Mate, guide book In hand.

On the way back, we pass the Kamppe Chapel of Silence. Located in one of the busiest squares in central Helsinki, it is built of three different types of wood – a spruce exterior, internal walls of alder, and furniture of ash – and offers a quiet refuge almost completely shut off from the noise and bustle outside. I close my eyes and imagine I am back in the bay at Skedöfladen surrounded by live trees of spruce, alder and ash, with only the calls of the grebes, heron and black-headed gulls. It kind of works.

“We certainly did pretty well for churches today”, says the First Mate over dinner that evening. “But one thing I know nothing about is what the difference is between Eastern Orthodox and Western Christianity. Why did they split up?”

“There was what they called the East-West Schism, as far as I remember”, I say, racking my brains. “In 1054 AD, or thereabouts.”

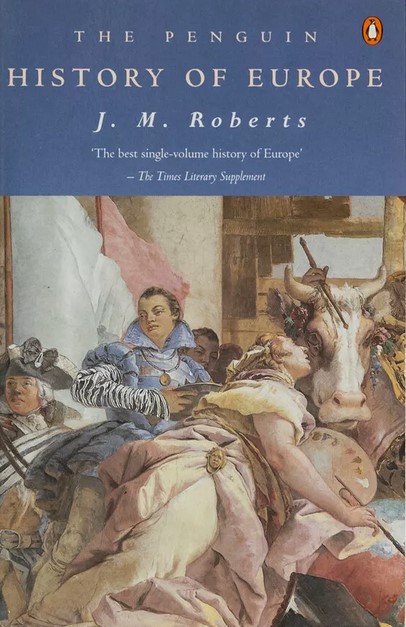

I consult our well-worn copy of the History of Europe by J M Roberts.

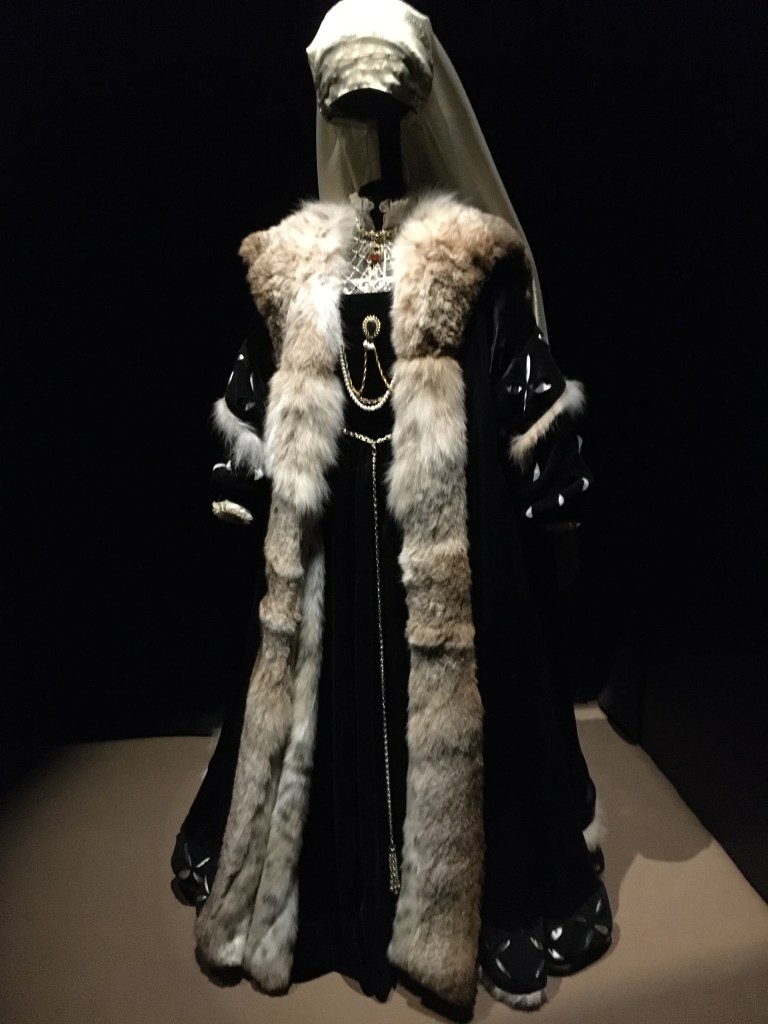

After Christianity spread through the Roman empire, the western and eastern parts slowly drifted apart, with different languages, rituals and practices, it tells me. The Eastern church promoted the use of icons, or pictures of Christ, Mary, the dead, the saints and the angels, to give people the feeling of being surrounded by the whole church. The Western church saw this as worshipping idols and were dead against it. They also disagreed over whether leavened or unleavened bread should be used in communion. And there were differences in some points of theology – the Eastern church saw the Holy Spirit coming from God directly, the Western saw it as coming from God and Christ.

“All pretty arcane, isn’t it?”, says the First Mate. “If God exists, I wonder why he didn’t make it all clearer so that there would be no room for misunderstandings?”

“Well, it was probably as much politics as theology”, I continue reading. “The Eastern church also didn’t accept the authority of the Pope in Rome over a universal church – they were much more into smaller national church groupings with their own leaders – the Armenian, Assyrian, Ukrainian, Russian, and so on. Anyway, to cut a long story short, they decided that their differences were irreconcilable, and split up into Catholicism in the west and Orthodox in the east. Of course, since then there have been any number of subsequent splits into sects and cults, each with its own interpretation of specific bits of scripture and claiming to be right.”

“Well, they can’t all be right, can they?”, says the First Mate.

The next morning we continue exploring Helsinki on the bikes.

“I’m impressed”, says the First Mate. “Absolutely stunning. A real library of the future.”

We are enjoying a coffee in the sunshine on the outdoors balcony of Oodi, Helsinki’s central library. She has a point. Commissioned as part of the centenary celebrations of Finland’s independence from Russia in 1917, it really is much more than a traditional library.

“Oodi is in effect a living room for the 21st-century city”, says the blurb. “As with other libraries in Finland, it is open and free to all. Their purpose is to promote reading, literacy, equality, and freedom of speech, as well as a sense of community and imagination.”

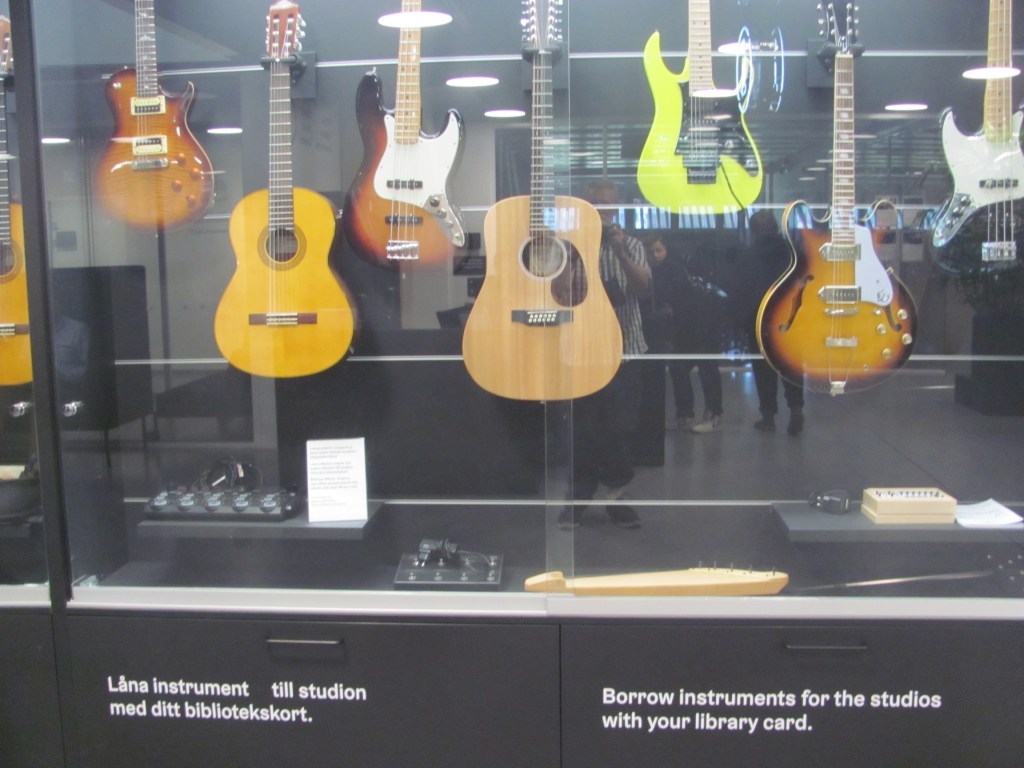

In addition to light, airy spaces for reading, there are also music and video production studios, a cinema, the café, and a restaurant. Meeting rooms on every floor can be used for lectures, talks and conferences. Weekly language classes are offered. On the second floor is an ‘Urban Workshop’ with laser cutters, 3D printers, sewing machines, and soldering equipment.

In addition to normal books, it is also possible to borrow e-publications, sports equipment, musical instruments, power tools, and other ‘items of occasional use’.

“It must be a great place to come during those long Finnish winters”, I say. “You could spend all day here, just reading, writing, keeping warm, meeting people over coffee or lunch. I am starting to see why Finland tops the ‘Happiness Index’ every year.”

“Did you see the robot which transports books from one part of the library to another?” asks the First Mate. “I had to wait while it got into the lift.”

“I read that a book that was borrowed from the library in 1939 was just returned the other day“, I say. “Apparently it was at the time the Russians invaded Finland in the Winter War. It seems that the borrower might have had other things on his or her mind and forgot to return it. It languished in an attic all those years, but someone came across it just recently and returned it.”

“I wonder if they had to pay an overdue fine?”, says the First Mate, standing up to go. “It would come to quite a bit for being 85 years late.”

In the afternoon, we meet up with Outi. We had first met her when we were on Kökar in the Åland islands, and we agreed to get in contact when we arrived in Helsinki, where she now lives. Over a coffee in the Kapelli restaurant near the Old Market Hall, she tells us that she comes originally from eastern Finland, in a part called Karelia.

“It’s actually now in Russia”, she says. “Finland lost it at the end of the Continuation War.”

“I don’t know much about Karelia”, says the First Mate. “Where is it exactly?”

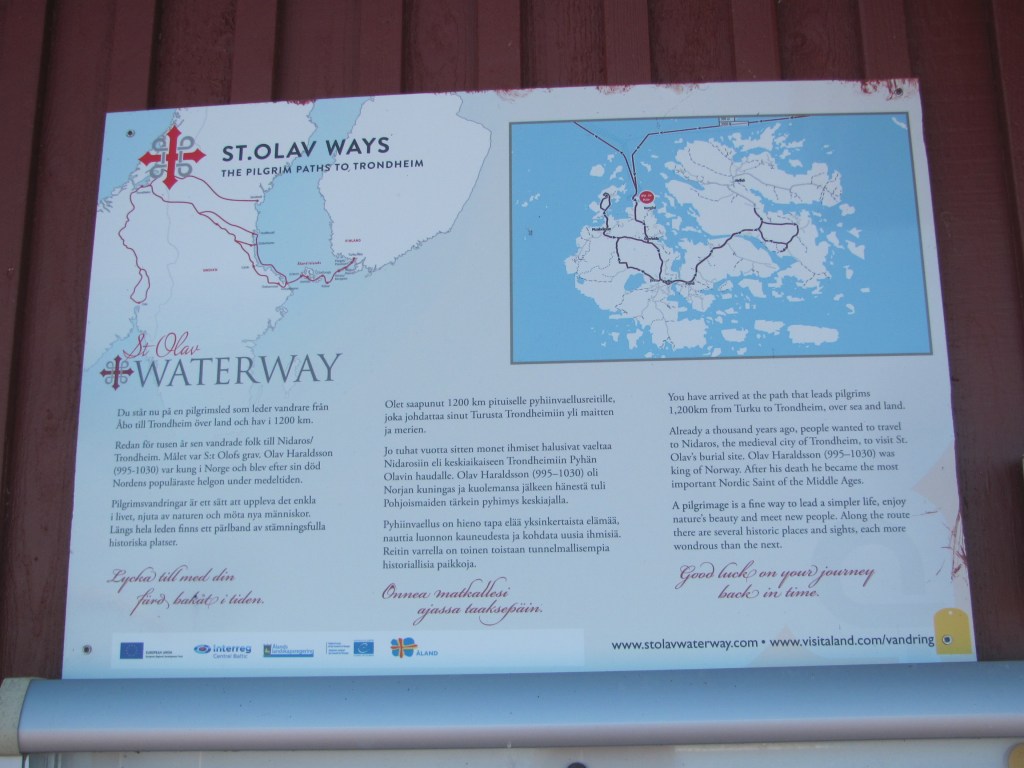

“Well, it’s an area between the White Sea and the Gulf of Finland”, she says. “We have our own culture and language, Karelian, which is very similar to Finnish. Unfortunately, because Karelia is only a small region with some large neighbours, we have never been an independent country. Back in the 1200s, we were fought over by the Swedes and the Novgorod Republic. In the 1300s we became part of the Swedish Empire. Then in the 1700s we became part of the Russian Empire along with Finland, and then part of the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland. So we have been close to Finland for quite a while.”

“What happened then?”, I ask.

“Well, Finland became independent in 1917, and Karelia along with it”, she answers. “That was fine, but the problems started in 1939 when Russia attacked Finland in the Winter War. The Finns fought bravely and held the Russians off, but the resulting peace treaty in 1940 meant that the Russians got to keep the land they had occupied, much of which was Karelia. A lot of Karelians fled at that time rather than be under Russian rule. My own mother fled with her family to north Karelia which was still in Finnish hands. She was only five years old.”

“So is that where she grew up?”, asks the First Mate.

“No”, says Outi. “When the Nazis invaded Russia in 1941, Finland decided to fight on their side to try and get Karelia and the other territories back. This became known as the Continuation War. They were successful for a time, and so a lot of Karelians, including my mother’s family, moved back to their own homes. Unfortunately, though, when the Germans started losing, the Russians pursued them, and fought the Finns too, regaining the land in Karelia. So the Karelians had to flee all over again. Now she lives in South Karelia, which is in Finland. We are going over this coming weekend to celebrate her 90th birthday.”

“It’s fascinating”, says the First Mate. “My mother has a similar story of having to flee from the Russians in Ostpruessen. What a terrible time it was for innocent civilians then. A whole continent in turmoil.”

“Yes, we are so lucky not to have experienced that in our lives”, says Outi. “At least not so far.”