“Quick”, says the First Mate. “That German boat is leaving. Let’s see if we can get out before it.”

But we still haven’t completed everything on our departure checklist, and the German boat, Compromise, manages to slip out in front of us.

“I was talking to the wife there yesterday”, the First Mate continues. “Apparently her husband gets angry with her when there is no wind. He hates using the engine, and because she does the route planning, he thinks it is all her fault if she plans a trip with no wind.”

“Well, he must be livid now”, I say. “There’s hardly any wind at the moment.”

We are just leaving Visby to sail to Bxyelkrok on Öland. Yesterday, we had bid farewell to Simon and Louise at Fårösund, as they were sailing directly across to the Swedish mainland where they plan to spend a few days chilling out anchoring in the archipelago before sailing to Kalmar where they are going to leave their boat over the winter. We are heading more southwards as we want to overwinter in southern Sweden. We had sailed from Fårösund to Visby to spend a night there to shorten the trip across to Öland.

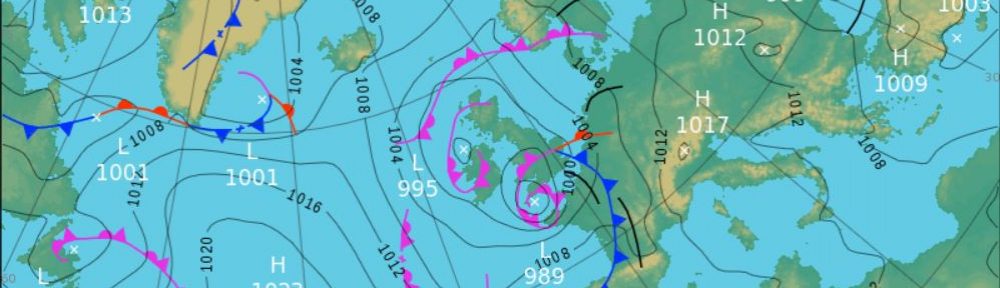

We motor out of Visby harbour behind Compromise. The wind is forecast to come from the southeast, but the headland to the south of Visby is making sure there is not much of it.

“I bet they are having a right old ding-dong over her taking them that way where there’s still not much wind”, says the First Mate. “If I was her, I’d tell him to do his own route planning, so he would only have himself to blame.”

But the wind picks up as we clear the headland, and before long we are unfurling the sails and are sailing along on a comfortable broad reach. We see Compromise to the south still motoring.

“Here’s a cup of tea”, says the First Mate. “Now, I am going downstairs to catch up on my emails.”

It is sunny and warm, and the sea is smooth. I sit back and relax, keeping a watchful eye on the instruments and the route ahead.

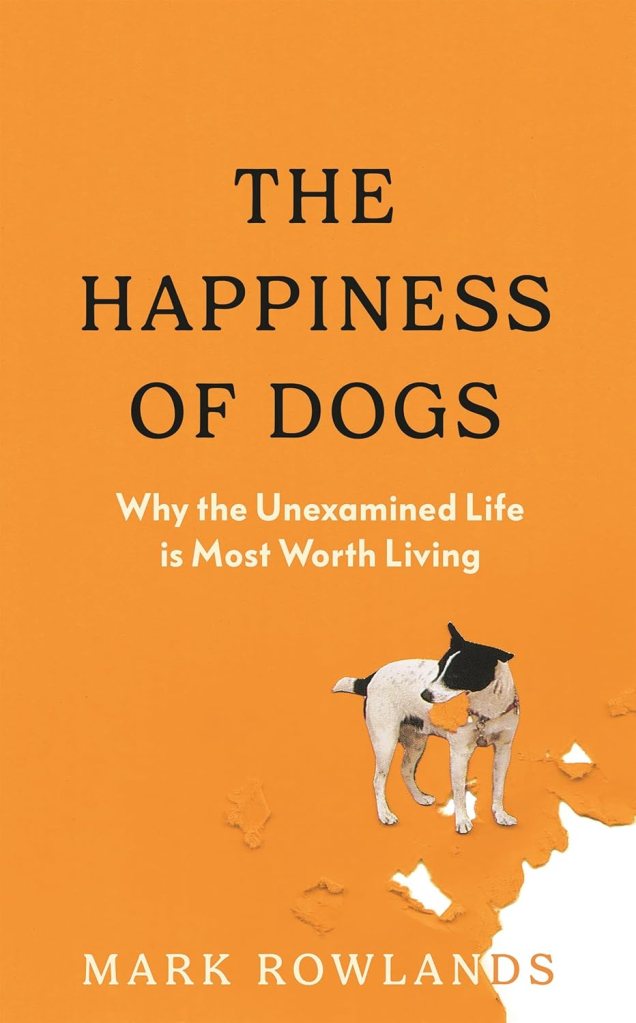

I think back to the newspaper article I had read this morning. Written by philosopher Mark Rowlands on his new book The Happiness of Dogs, he discusses what dogs can teach us about the meaning of life. Dogs experience unbridled joy from the simple things in life, he says, regardless of whether they are repetitive or not. They will always be ecstatic when they are about to be taken for a walk, even though it might be along a path they have been hundreds of times before. For dogs, happiness comes effortlessly.

Us humans on the other hand torture ourselves with trying to find meaning in our lives. What makes our existence worth the bother? We construct elaborate myths and narratives to convince ourselves that we are here for a purpose, that we are part of a grand plan. We must make progress – doing the same thing day after day appears to us to be meaningless, like Sisyphus’s task of pushing a rock uphill only to have it roll to the bottom again at night.

Rowlands puts all this down to our ability to reflect – we are always thinking about ourselves, scrutinising and evaluating what we do, and why we do it. Dogs, on the other hand, rather than think about the answers to the meaning of life, just live it to the full.

Not far behind us, I spot Compromise following us, her sails up now. I trim our sails and manage another half a knot. Wherever there are two boats there will be a race, whether we admit it or not.

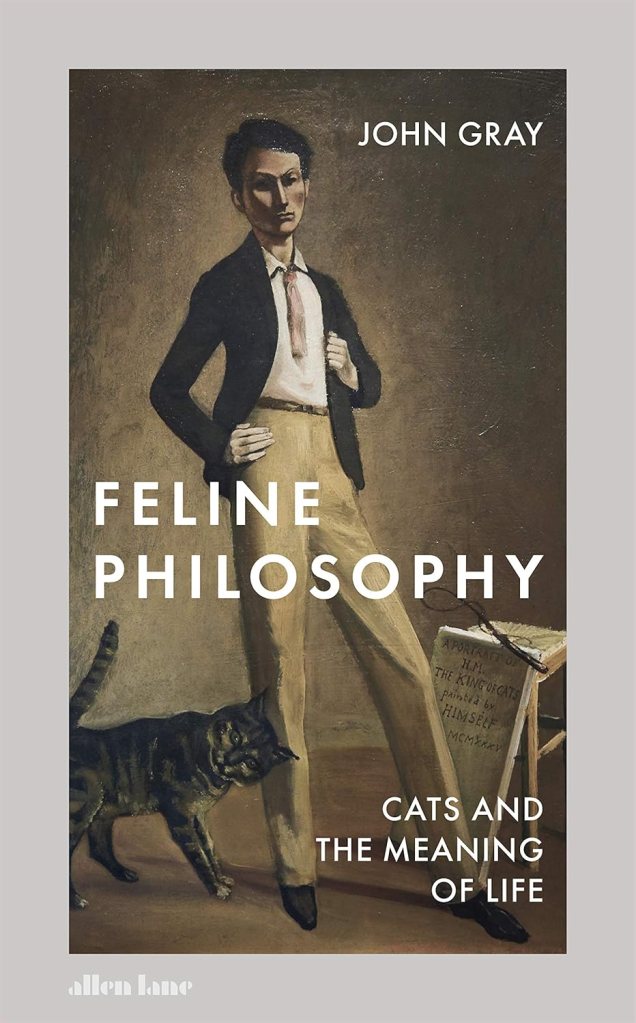

Rowlands’ ideas remind me of John Gray’s book Feline Philosophy: Cats and the Meaning of Life, which I had read a couple of years ago. In it, he draws similar conclusions from cats. Cats live for the sensation of life, he says, not for something they might achieve or not achieve. Humans, however, tell themselves stories that might provide the illusion of calm in a chaotic and frightening world, that everything is under control. Even though most of the things that happen to us are pure chance, we still struggle with the idea that there is no hidden meaning to find. He advises us to leave our ideologies and religions to one side and just enjoy the sensation of life.

I notice that we are slowly pulling ahead of Compromise. She is at least half a mile behind us now. I tweak the sails a little bit more.

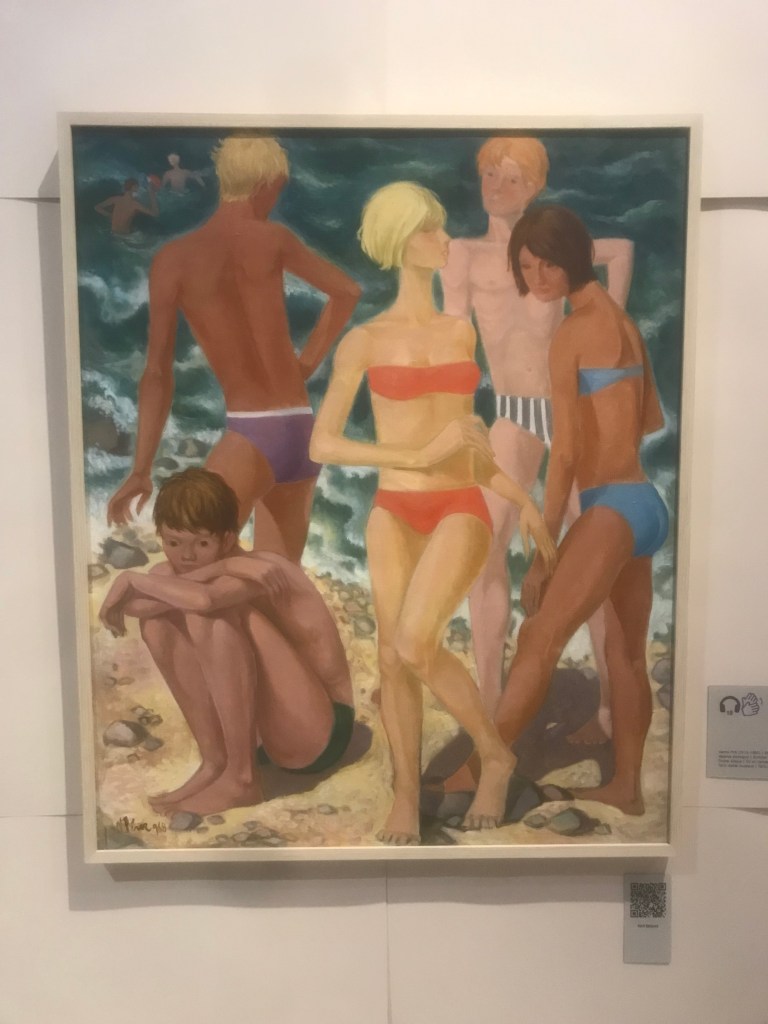

But would we just want to live for the moment like dogs and cats?, I wonder. Even if consciousness, self-awareness, and the ability to reflect make us anxious, troubled creatures, would we want it any other way? Would we want to give up the appreciation of the beauty of art, science, music, and all that we have achieved as a species? Isn’t it part of what being human means?

“Can you see Öland yet?”, calls the First Mate, bringing out a mug of hot tea and a digestive biscuit.

“We’re getting close”, I say. “I can see the lighthouse at the northernmost point. By the way, I looked up what Byxelkrok means. It translates as ‘The Village Forests Bend’. Apparently the Vikings called it that as they had to turn south at the point to get to their port at Tokenäs, a few miles from Byxelkrok.”

The marker buoy showing the entrance to Byxelkrok harbour appears, so we furl the sails and motor in. Soon we are tied up safely next to a Danish family who are travelling north to Stockholm. Out of the corner of my eye, I spy Compromise following us into the harbour. Ha, we beat you, I think to myself.

The next morning dawns bright and sunny, but windy.

“Let’s get the bikes out and cycle up to the lighthouse at the top of Öland that we passed on the way here”, says the First Mate. “I’ve heard that it is a nice ride.”

We cycle along a tarmac cycle track parallel to the shore line.

In the distance, we can see Blå Jungfrun, the fabled island in Swedish folklore where witches are supposed to meet every year on Maundy Tuesday and swap spells.

Along the way, I feel the need for a pinkelpause. We stop at an overgrown track leading into the woods.

“Didn’t you see the sign?”, asks the First Mate. “Look there’s a house over there through the trees. You’re probably on someone’s webcam now. We might have the police knocking on the boat tonight.”

“I am amazed someone has gone to the trouble of putting up a sign”, I say. “They must get a lot of people with the same intention.”

We eventually reach the lighthouse.

“Långe Erik lighthouse was built in 1845 out of local limestone”, the nearby panel tells us. “At first the lamp used mirrors and burned rapeseed oil. But this required constant attention, they were later replaced by mirrored lenses and a paraffin lamp. The lamp was changed to electricity in 1946, and in 1976 was fully automated.”

How many lives has it saved, I wonder. This is a treacherous piece of coastline.

“Come and have a look at these piles of stones on the beach”, calls the First Mate from behind the lighthouse. “They look like an army of invaders from the sea. I wonder how long they will stay up in this wind?”

In the morning, we leave Byzelkrok and sail down to a small harbour by the name of Stora Rör, still on Öland. The harbour is almost full, but luckily there is one berth remaining for us. We squeeze in, helped by the German couple next to us.

“I’ll go and pay the harbourmaster and bring an ice-cream back”, says the First Mate. “You finish tying the boat up.”

It’s a picturesque little place, with a bakery and a restaurant right next to the marina. And a popular weekend haunt judging from the number of people milling about, talking, eating, drinking and generally enjoying the warm sunshine. It is sometimes surprising to remember that places that we imagine to be remote when arriving from the sea are well connected by road and readily accessible to the rest of civilisation.

——-

I watch as the bucket disappears into the depths of the well and splashes into the water far below. A cock crows – it is early in the morning, and the village is still asleep. I wait for a few moments for the bucket to fill, then pull as hard as I can to lift it out. Some water sloshes out and back into the well as I lift it over the stone wall, but there is enough to keep my mother happy, and I carry it back through the deserted streets to our hut near the east gate of the wall surrounding the village. She is already up and has started the fire, its smoke filling the hut and making my eyes water.

She hands me a clay bowl of oat porridge boiled in milk. As I gulp down the last drops, there is a shrill call from outside our hut.

“Erik, Erik, come and play with us!”

It’s Frida, the young girl from next door, her flaxen pigtails bobbing with excitement.

“Off you go”, says my mother. “But don’t forget that your father wants to take you up to the walls today.”

We run through the narrow passageways between the houses, sometimes playing hide-and-seek, other times playing soldiers, guarding the gates against invaders with our little wooden swords and bloodcurdling battle cries. Later I climb the walls of the fortress with my father, and look out at the fields and forests on the outside. Even though it has been peaceful for some time, I know that the wall was built to protect us from our enemies, and that our warriors need to be on the constant lookout for danger. I will be one of them one day.

As the sun sets in the evening, torches are lit around the fortress, their warm glow giving a golden hue to the stone walls. The whole village gathers in the central courtyard to share food for the evening meal. After eating, I sit by the fire feeling safe and warm, listening to the adults tell stories of the gods and heroes.

I am brought back to the present by a buzzing in my ear as a bee lands on an orchid in front of me. I am in the ruins of Ismantorp Fortress, an Iron Age fortified village near the centre of Öland, and am imagining what it might be like from the perspective of a young boy living there in the fourth century.

I had cycled up to the fortress after we had arrived at Stora Rör, and had marvelled at the massive circular stone wall, the stone foundations of 95 houses arranged inside each separated by a narrow alleyway, and the central public square with a pit.

“The Ismantorp Fortress is an enigma”, says the panel. “The walls suggest that it had a defensive function, but it is a puzzle why there are nine gates. Gates are hard to defend, so it makes more sense to have just one or two. Some experts think that it might have been a fortified religious centre similar to some Slavic castles. Other theories say that it might have been a training centre for warriors.”

Whatever its purpose, archaeological digs so far have unearthed only an arrowhead and a belt buckle, suggesting it wasn’t lived in intensively, or was abandoned deliberately over a period of time. More digs are planned, but for the moment Ismantorp remains an enigma.

On the way back, I get a puncture. I must look a bit forlorn, as a couple of cyclists stop to see if I need any help. Luckily I have the puncture repair kit with me, and I assure them, not entirely convincingly, I will probably manage.

“Well, if you do need any help, our car is just parked over there”, they say, pointing to a small car park. “We’ll be there for a while loading our bikes and having a coffee. Feel free to come over if you can’t fix it.”

It’s good of them. But I manage to get the wheel off and the tube out, find the hole by listening for the whistle of air, apply the rubber solution around it, wait for it to dry, then put on the patch. It works! Waving a cheery thank you to the other cyclists, I continue on my way.

In the evening, we have dinner at the restaurant with Klaus and Claudia, our German neighbours. They are from Mannheim, and have been cruising the Swedish archipelago in their boat, Saari.

“Saari is the Finnish word for ‘island’”, says Claudia. “We’ve been exploring the islands of the Swedish archipelago in her, but we are on our way back home now. We have to be back in Greifswald by the end of the month to meet Klaus’s son.”

“I’ve been sailing most of my life”, Klaus tells me, as the beers arrive. “My father was a great sailor. I learnt to sail on Lake Constance. He taught me everything I know. I’ve passed it on to my son, who is also an excellent sailor.”

I suddenly feel very inexperienced. At least I know the pointy end is the front, and the blunt end is the back.

“They’re called the bow and the stern, aren’t they?”, says the First Mate helpfully. She’s the expert.

When we get back to the boat, I decide to have a post-prandial dram before turning in.

“These ring fortresses are quite interesting”, says Spencer, swinging by a thread from the canopy. “It was during what is called the Migration Period in European history, between AD 300-500. At the time the Western Roman Empire was declining, and its weakness allowed lots of different peoples to migrate across the continent. It was a chaotic time and people built fortified villages to protect themselves from marauders.”

“What sort of peoples do you mean?”, I ask.

“A lot of it was driven by the Huns”, he responds. “They invaded from the steppes of Asia, and their military prowess and brutality allowed them to sweep across Europe. Then there were the Goths who were originally from Scandinavia, but had already migrated from there to present day Poland, and were pushed by the Huns from there to the Black Sea area, from where they attacked and destroyed Rome. One branch, the Visigoths, ended up in Spain, while another, the Ostrogoths, established themselves in Italy. Other tribes were the Slavs and Avars who pushed into Europe from the east. Once all this movement had settled down, the resulting pattern of people formed the basis of the different nations that we see in Europe today. So in a sense, you are all descended from migrant stock.”

“But that was all on continental Europe”, I say. “Why would they need to build fortified villages here in Öland? Weren’t they out of all this chaos?”

“Well, Öland was quite well connected during this period,”, he answers. “Not only because of its shared cultural and religious practices with the Germanic world, but also because it was part of a trading network with the rest of Europe. Goods such as amber, furs, and even slaves were traded, and Roman coins have been found on Öland. Even though it wasn’t affected by the mass migrations in other parts, it would nevertheless have been exposed to the influx of new ideas, technologies, and people, and the unrest that they bring.”

“Time to go to bed”, calls the First Mate from the cabin. “That’s enough talking to that spider. You’re stopping me from sleeping. We need to get going in the morning.”