I awake, and lie listening to the low rumble of the first ferry arriving and opening its door to the waiting traffic. Perhaps losing the camera was a bad dream, and it is still there on the shelf?

But it isn’t.

On the way back from the shower block, I notice that the Nice Harbourmaster is back in her office. I decide to mention the lost camera to her on the off-chance that she might know if there is a place on the island that lost property might be handed in to.

“We have an island intranet where such things are posted”, she says immediately. “Here, I’ll put it on straight away. Tell me all the details of your camera.”

I describe the camera as best I can while she types it in.

“There”, she says, pressing the Send button. “It’s a long shot, as it depends on an islander having found it, and not a tourist. Unfortunately, it’s usually tourists who visit the Muhu Linnus and not locals. But you never know. If it turns up, I can post it on to you.”

It’s the best we can do. If I am lucky, I might get it when we get home.

We prepare to leave. I run through the check list. We also need to top the tank up with fuel. This time we have transferred enough money into the account, so the card should be accepted.

As I am turning on the navigation instruments, the First Mate calls down from the cockpit.

“There’s someone here to see you”, she says. “Come up quickly.”

It’s the Nice Harbourmaster.

“I have some good news for you”, she says, smiling. “Your camera has been found. They are bringing it here now. By a strange coincidence, it was found by one of my friends who was at my birthday party.”

A few minutes later, a car pulls up to the harbour office. It’s been only half-an-hour since I first mentioned it to the Nice Harbourmaster.

“It was my wife who found it”, the driver tells us. “We live near there, and she had taken the dog for a walk and came across it. It was raining, so she took it so it wouldn’t get damaged.”

He hands back the camera. I am overjoyed. My faith in human nature is reconfirmed.

“I hope you don’t mind, but I went through your photos”, he says. “I was trying to get an idea of who might have lost it. I could see you were sailing and that you were interested in historical sites.”

“Not at all”, I say. “I am so glad that she found it. I had resigned myself to never seeing it again.”

We refuel and set off, heading for Pärnu. As we leave, I see a cloud formation of a dove flying. A sign!

“It’s just pareidolia”, says Spencer. “You are pleased that you got your camera back again, and it’s making you see positive patterns in abstract things around you. It’s just water vapour.”

Does he ever enjoy himself?, I wonder.

We stop off for the night at Kihnu, a small island just off the eastern coast of the Gulf of Riga. Settled originally by criminals and exiles from the mainland, the men took to seal hunting while the women specialised in handicrafts and music. Motorbikes with sidecars are also a thing.

The next day we reach Pärnu. The previous week, the Gulf of Riga Race for sailboats had finished in Pärnu, and there are still a few of the boats and their crews in the marina. But we manage to find a berth.

Pärnu (pronounced (Per-noo) is the fourth-largest city in Estonia. Like the other towns we had visited, the original town of Pärnu was founded by the Bishop of Ösel-Wiek on the north side of the river after the local pagan stronghold, Soontagana, had been conquered by the German Crusaders. Around the same time, the Livonian Order built a military town called New-Pärnu on the south side of the river, with the river the boundary between the two territories. The latter gradually eclipsed the older town, mainly through its prosperity gained through its membership of the Hanseatic League. Old-Pärnu was later destroyed. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had control of New-Pärnu in the 1500s, but then its history followed the broad outlines of the rest of Estonia – flipping between control by the Swedes, the Russians, the Germans, then by the Soviets again, with a brief period of independence in between.

We unload the bikes and explore the city. It has some charm, with churches, an impressive town hall, and old wooden houses nestling quietly amongst leafy avenues.

We reach the Swedish Gate, the only remaining entry through the old city walls, so-called because the Swedish built it during their stint of ruling it.

At one end of Independence Square is the monument to the Proclamation of Independence in 1918, which was read out from the balcony of one of the surrounding hotels. In this sense, Pärnu is the birthplace of the modern republic of Estonia.

We end up at the museum, where we learn about the rise and fall of the Baltic Sea level since the Ice Ages.

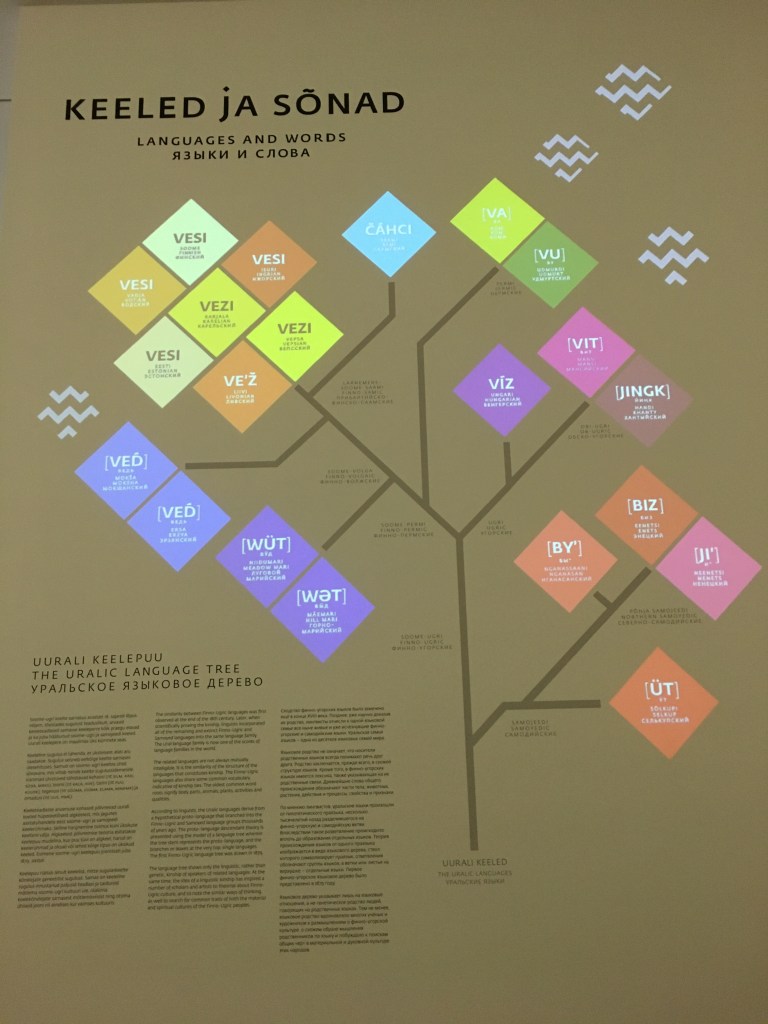

“The Baltic was a vast ice lake left behind after the retreat of the glaciers at the end of the last Ice Age”, a panel tells us. “As the Earth continued to warm, the ice in the lake slowly melted, and the freshwater from it flooded out into the North Sea across the lowlands of Sweden through a channel roughly where the Göta Canal is nowadays. This created the Yoldia Sea, which was brackish due to the salt water flowing in the opposite direction when the levels were similar. However, as the land rose after the weight of the ice was gone, it cut off this route to the North Sea, creating the freshwater Ancylus Lake. Then as the sea-level of the North Sea rose, it broke through the narrow gap between Sweden and Denmark, and salt water flooded in, creating the brackish Littorina Sea. That’s more-or-less what we have today.”

“It’s fascinating to think of all that going on, isn’t it?”, says the First Mate. “You tend to think that everything you see has been the same forever, but these comings and goings all occurred fairly recently. And I wonder how these various seas and lakes got their names? Hardly likely to be the people living there at the time, is it?”

“It seems they are named after species of molluscs that live in different levels of salinity”, I say, consulting Google. “That’s how they worked out what was going on.”

The Red Tower, once part of the old city walls, then a prison, is now part of Pärnu Museum.

“The guide book says it’s worth seeing”, says the First Mate. “It has an interesting panoramic cinema showing the history of Pärnu.”

We climb the narrow staircase to the top floor, and sit fascinated watching how the city developed from a seal hunters’ camp, a Viking trading post, through medieval times, the various occupations, independence, to the modern day.

“For years our country has been the battleground of foreigners”, the voice-over says. “But hopefully that is the end of that now that we are an independent and free state.”

It’s time for a coffee and a cake.

“The beach is supposed to be very nice”, says the First Mate, as she cuts the cake. “Why don’t we buy some food and have a little picnic there later on?”

“Sounds like a good idea”, I say.

We cycle down to the beach and find a bench to sit on. It’s late afternoon, the sun is warm, and quite a few people are still there. We strike up a conversation with a dad with his young daughter and his mother sitting at the other end of the bench.

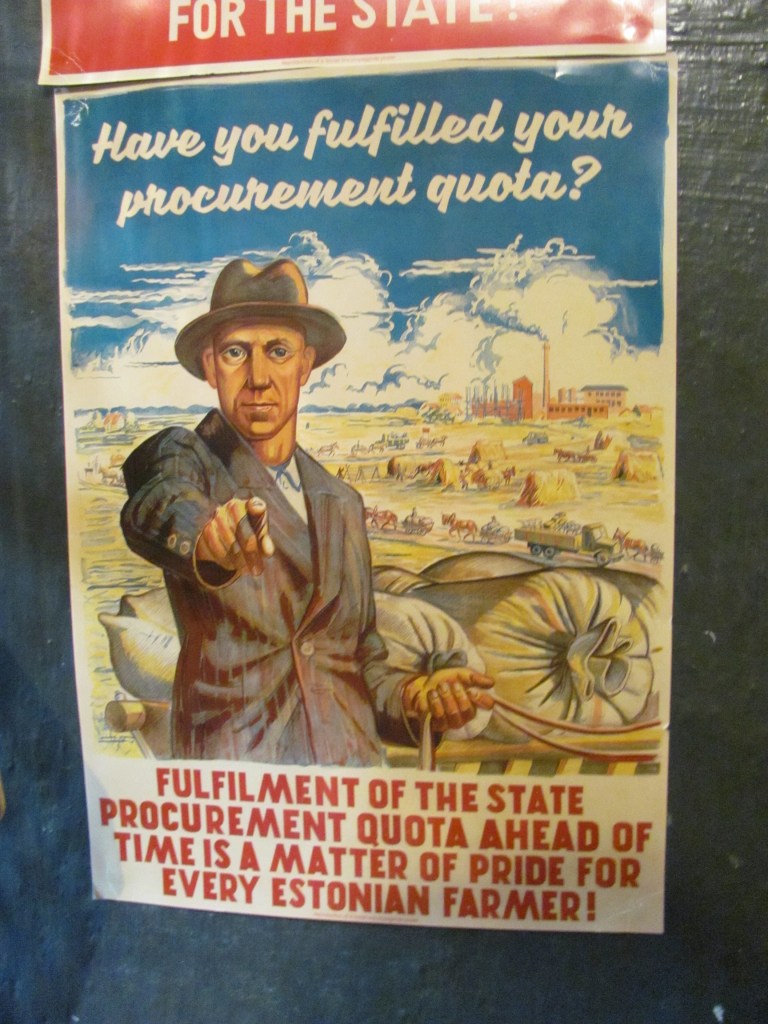

“Yes, we are Estonians”, he says. “Not Russians. We’ve lived here all of our lives. I used to come down to this beach when I was a child. Now I am bringing my daughter here.”

“We used to come here and sit and look across the water, wondering what countries lay beyond”, says his mother. “Of course, in those days of the Soviet Union, there was no chance to travel to see them. We used to dream of a white ship coming to take us away to see the rest of the world.”

“The ‘white ship’ is a symbol of hope in Estonian culture”, the Dad explains, seeing the puzzled looks on our faces. “It started back in the 1800s when a leader of a religious sect in Tallinn called Prophet Maltsvet promised his followers that a white ship would come and take them away to a better land. But it never arrived. Since then it has become associated with deliverance from repression in general. Estonia has had a difficult history, and it helped to give people hope that things would get better.”

The First Mate invites them to come and see our ‘white ship’, but they don’t have time.

The next morning, we set off for Salacgriva, a small harbour just inside the Latvian border. It’s about halfway between Pärnu and Riga, and an ideal place to break the journey.

After tying up, we sit in the cockpit and sip our glasses of wine, unwinding. Suddenly, there is a roar of a speedboat driven by a young chap that zooms past us. The wake rocks Ruby Tuesday violently.

“Crazy idiot”, shouts the First Mate, brandishing her fist at him. “Can’t you think of someone else besides yourself for a change?”

Eight water-skiers follow, attached to the speedboat. They are practising for the regatta that is to be held at the harbour at the weekend. Thinking she is waving, one manages a quick wave back.

“Oh, sorry”, she says, embarrassed. “I didn’t mean to be so cross. But I just wish they wouldn’t come so close.”

“They wouldn’t hear you anyway over the noise of the engine”, I say.

After dinner, we go for a walk to the nearest village. The supermarket is about to close. We have a quick browse through. One thing that we are struck with is the number of Russian items for sale, something that wasn’t so evident in Estonia.

“Hey, put that packet of Russian Earl Grey teabags down”, says the First Mate. “We don’t want to support the Russian war effort in Ukraine.”

We carry on the next morning, aiming for Riga. As we sail, I continue with the book I am reading, Twilight of Democracy – The Failure of Politics and the Parting of Friends, by Anne Applebaum, the historian. In it, she discusses the rise of authoritarianism around the world, and the apparent decline in democracy.

Authoritarianism is not a philosophy or ideology, she says, but just a means of holding power. Loyalty, not ability, is the criteria for success. She asks the question of whether a liberal world promoting free speech, rational debate, respect for knowledge and expertise, and freedom of movement, is just a cul-de-sac in the broad sweep of history? Is democracy in its twilight, with a reversion to anarchy or tyranny on the cards?

“Ah, but the book was published in 2000”, says Spencer, emerging from the canopy. “Since then Poland has swung away from the Law & Justice Party, the UK has voted out the Conservative Party and its far right wing, and in France the National Rally was beaten into third place. Now it remains to be seen what happens in America with the coming elections. A battle between a young, mixed-race, democratic woman and an old, white, autocratic man. Perhaps the pendulum is starting to swing in the opposite direction again?”

I am just about to answer when the VHF crackles into life.

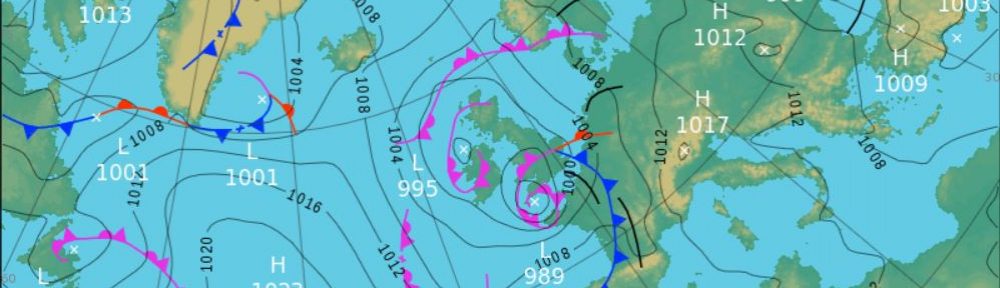

“Gale warning for all shipping. This is to announce a gale warning in the Gulf of Riga. All ships should take immediate action and seek shelter.”

I am puzzled. The weather forecast in the morning had predicted strong winds in the evening, but not gale strength and not so early in the day. Our plans had been to be safely tied up in Riga well before they started.

“I think that we should find somewhere”, says the First Mate. “I don’t really want to be caught out in a gale. We still have about four or five hours to get to Riga. Isn’t there a small harbour about halfway?”

There is. A place called Skulte. After some discussion, we decide to alter course and put in there.

“Better to be safe than sorry”, the First Mate says, looking happier.

We follow the marker buoys into the harbour. Large ships are moored alongside the wharfs, with cranes loading timber into them. Huge piles of wood chips lie on the quay like small mountains. We learn later that the timber is shipped off to Sweden by Swedish companies, made into furniture, and sold back to Latvia.

The marina is a little way up a small river opposite a fishing wharf. We are met by the harbourmaster.

“Not many yachts come here”, he says. “Only those looking for shelter on the way to Riga.”

We tell him about the gale warning.

“Ah, the meteorological people are always exaggerating”, he says. “Anything more than a gentle breeze, they call a gale. They probably have to do it to cover themselves.”

Recollections of the ‘Boy who cried Wolf’ story from my childhood days flood back. Would anyone believe them if it really was a gale?

“But it’s true there are strong winds coming tonight”, he continues, as though reading my mind. “Although I don’t think they will be gale force. Either way, you’ll be safe enough in here.”

Somehow I manage to stub my toe on a cleat on the pontoon as we are tying up. It rips the toenail almost off. Blood is everywhere.

“I think that needs seeing to”, the harbourmaster says, shaking his head and looking at it like a mechanic looks at a car needing an expensive repair. “There’s a hospital not far from here. I am quite happy to take you there and wait while they fix it up.”

It seems a bit like overkill to go to a hospital, but I don’t want problems down the line if it gets infected. I climb into his car, trying to make sure I don’t get any blood on the seats. The First Mate wedges herself into the back seat.

“Sorry about the dog hair and the smell”, he says. “We have a dog at home who comes everywhere with us.”

We arrive at the Trauma Unit of the hospital. Luckily a doctor can see me almost straightaway. He doesn’t say anything, but motions me to lie down on the bed. I assume he doesn’t speak English. He picks up an evil-looking curved pair of scissors and deftly cuts the remaining nail off at the quick and dresses the wound.

“I wonder if that’s it?”, I say to the First Mate, who has almost fainted in the corner at the sight of so much blood.

“No”, says the doctor in perfect English. “One more thing. You must pay!”

“He probably worked for the KGB in the old days”, the harbourmaster jokes on the way home. “They were pretty good at pulling out fingernails and toenails.”

I am going to have to get used to Latvian humour.