We leave Helsinki the next morning, bound for Estonia on the other side of the Gulf of Finland, a distance of some 50 nautical miles. As we leave, we pass the clubhouse of Nyland Yacht Club, made famous in Arthur Ransome’s Racundra’s First Cruise. In fact, we have decided to retrace his journey on Racundra to and from Riga as much as possible, albeit in the opposite direction sometimes.

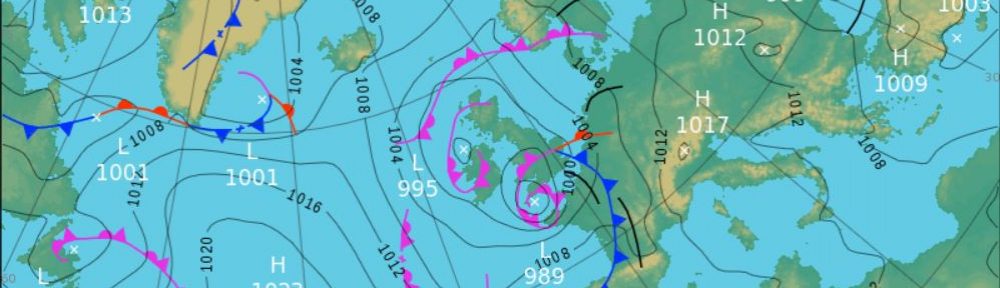

Although light at first, the wind picks up, and before long we are sailing on a fast close reach. We cross the Traffic Separation Scheme at right angles, taking care to stay away from the several Russian freighters that we see on the AIS heading for St Petersburg. One never knows what they might be carrying.

We eventually reach the small island of Naissaare just north of Tallinn, and decide to stay there the night. We had been recommended to stop there by some Estonians we had met in the Southern Finnish Archipelago.

“There are some great walks here”, says the harbour-mistress as we check in. “During Soviet times the island was used to make and store naval mines, and it was forbidden to visit the place. Now you can roam everywhere. Here, take this map. It shows you where to go.”

Despite some ominous looking rain clouds, we set off.

“What a weird place”, exclaims the First Mate. “All these mines and old military equipment just lying around. I just hope none of them still have explosive still inside them.”

On the walk, we meet another couple, and we walk together for a little while along the small railway line that was used by the Soviets to transport mines from the storage sheds to the harbour.

“Naissaare translates as ‘Island of Women’”, they tell us. “The story is that a community of fishing families once lived here, and with the men all away at sea, only women were left on the island. We don’t know if it is true or not, but if it is, it must have been a while ago as it was mentioned by a medieval chronicler in the 11th century.”

The next day, we arrive in Tallinn after a short sail from the island. We tie up at the Lennusadam marina, which also happens to be right next to the Maritime Museum. On the other side of the jetty a destroyer of some sort is lying.

“We should be safe here with that thing next to us”, says the First Mate.

I notice that its guns are pointing towards the city, not out to sea.

“Tallinn is a beautiful old medieval walled city dating from before the 11th century”, the guide book tells us. “The Danes conquered it in the 1200s, the German Knights of the Sword took it a few years later. It later joined the Hanseatic League as a trading post between the Russian Novgorod and Europe, but faded in the 16th century when the Hanseatic League declined. Sweden conquered it in the 1500s, then the Russians in the 1700s. It managed to become independent of the Russian empire in 1918 until it was invaded by Stalin in 1940, then by the Nazis in 1941, and again by the Soviets in 1944. It only became independent again in 1991.”

“They’ve certainly had a roller coaster ride with their neighbours”, says the First Mate.

“Now, I suggest that we take one of the free walking tours organised by the Tourist Information”, she continues. “There’s one that focuses on the Soviet period in Tallinn. That sounds interesting.”

We join a tour starting just after lunch. The leader is a studious young man called Marco.

“I am a history teacher”, he introduces himself in excellent English. “I am actually Bulgarian, in that I was born in there, but my mother is Estonian, and I have lived in Estonia for most of my life. My mother’s mother was an Estonian Jew. There weren’t many Jews in Estonia compared to some of the other Baltic States, but when it looked like the Nazis would invade, many escaped to the Soviet Union. My grandmother’s family was amongst them. Those Jews that remained – around 1000 – were almost all killed by the Nazis. After the war, she wanted to return but wasn’t allowed to live in Estonia, so she settled in Bulgaria, met my grandfather there and raised a family, one of which was my mother.”

It’s quite a moving story, and it adds a personal touch to the tour.

We pass the Russian Embassy. The iron railings outside are covered in placards, flowers, and pictures expressing protest against the war in Ukraine. An effigy looking like a bride is daubed with red paint.

“It’s to signify the blood of the innocent that is being spilled there”, explains Marco. “Most Estonians are supportive of Ukraine’s efforts, as we know what it is like to be under Russian rule. We don’t want to go back to those times ourselves, and we can understand why the Ukrainians want their freedom too.”

“What about the ethnic Russians who live here in Estonia?”, someone asks. “What do they think?”

“Ah, good question”, says Marco. “Something like 24% of the population of Estonia is ethnic Russian. Here in Tallinn, it is nearer 40%. Most are construction workers and the like that came during the Soviet times to work on infrastructure projects, and stayed on. When we regained our independence, they weren’t granted Estonian citizenship automatically, but were given the option of applying for it through naturalisation.”

“The problem is that they have never really integrated”, he continues. “Most don’t speak Estonian, and they have their own Russian schools where they learn only Russian. Because you need to be able to speak Estonian to gain Estonian citizenship, most of them are classed as ‘non-citizens’. In any case, as dual nationality is not allowed, many ethnic Russians prefer not to take Estonian citizenship as they can still travel freely to Russia to visit friends and relatives rather than having to obtain a visa. The problem is though, that because they don’t speak Estonian, they don’t get very good jobs, so that the predominantly Russian areas in Tallinn and the east of Estonia have a lower standard of living than the rest of the country.”

“But to go back to your question, about 60% of Russian speakers in Estonia are against the war in Ukraine, especially the young people.”

We move on to the next stop on the tour, the notorious KGB cells at 1 Pagari Street.

“We won’t be going into the cells on this walking tour”, says Marco. “But I strongly recommend that you come back later and see them, as well as the Paterei prison. This is where anyone suspected of being anti-communist was brought to be interrogated. Most who came were either killed here, imprisoned in Paterei, or else deported. There is an Estonian joke that it must have been the tallest building in Tallinn, as if you entered it, you could see all the way to Siberia.”

He pauses. No one is quite sure whether to laugh or not.

“But let me tell you another relevant family story”, he continues. “Just after my parents got married, my mother’s mother came to live with them in their small apartment in a Soviet style block. She was a strong supporter of Estonian independence and became involved in some of the activities. One day my father announced that they would be moving into a bigger and better apartment. They were all a bit puzzled, but were happy to have more space. Then when my grandmother died, my father confessed to my mother that he had been informing on her mother to the KGB for years as she was a ‘person of interest’ to them. He had been given the bigger apartment as a reward.”

“What did your mother think?”, someone asks.

“Well, she felt so betrayed by him that she left him”, Marco says. “We were brought up by her to think that he was a terrible person. But more recently, I have come to realise that although he was flawed and made a bad choice, he wasn’t evil. It’s easy to be critical if you haven’t lived through the same circumstances yourself. Now let’s go and see the ugliest building in the whole of Estonia. That will be the end of the tour.”

We reach the so-called Tallinn City Hall on the waterfront. Ugly doesn’t even really start to describe it.

“It was built for the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow”, Marco explains. “As there was no suitable venue in Moscow for the sailing, they decided to hold it in Tallinn. It was called the Lenin Palace of Culture and Sport, and in addition to being a place to watch the sailing, it also contained a skating rink and concert hall. The problem is that because Soviet construction methods are not noted for their quality at the best of times, and because it was also built in a hurry, it is extremely poorly built and most of it is very dilapidated now. But no one knows what to do with it. In some ways, it should be pulled down, but it has heritage protection. There has been talk about restoring it, but nothing has happened yet as it will be too costly. So it sits here, decaying even more.”

He’s been a great guide. We thank him for his introduction to the city and say goodbye.

Later, we return to 1 Pagari Street, the KGB cells. The outside world fades as we climb tentatively down the worn stone stairs to basement level. I shiver involuntarily as I think of the many people that must have passed down these same stairs, perhaps knowing that they would be tortured until they confessed to something they never did.

The cells are both sides of an underground passageway, the atmosphere dank and clammy. I try and imagine what it must have been like to be imprisoned down, but having been brought up in a time of relative peace, and knowing that I can leave whenever I want, I just don’t have the mental machinery to appreciate the true horror of the place.

Many of those incarcerated belonged to the ‘Forest Brothers’, a group of partisans who fought against the Red Army in both periods of occupation. They fled to the forests when the Soviets arrived in 1940, helped the Nazis to drive them out again in 1941, and waged a guerrilla war against them after Soviet reoccupation until they were wiped out by superior Soviet forces in the 1950s.

In the last cell, we are asked which freedom is the most important to us. A poignant response from a previous visitor catches my eye. He or she is from Belarus.

“I just want the KGB in my home country to be turned into a museum like this”, it says. “And not be able to conduct illegal interrogations and torture. I was an environmental activist, and when the KGB came to my home in February to detain me, I fled. They arrested my mother instead and kept her in an unheated cell for 12 days with no warm clothes. My uncle was arrested and beaten because he attended a peaceful protest against unfair elections. His kidneys were damaged and he was raped with a police baton.”

Such horror is not a thing of the past.

The next day we cycle over to the Vabamu Museum of Occupations not far from Freedom Square.

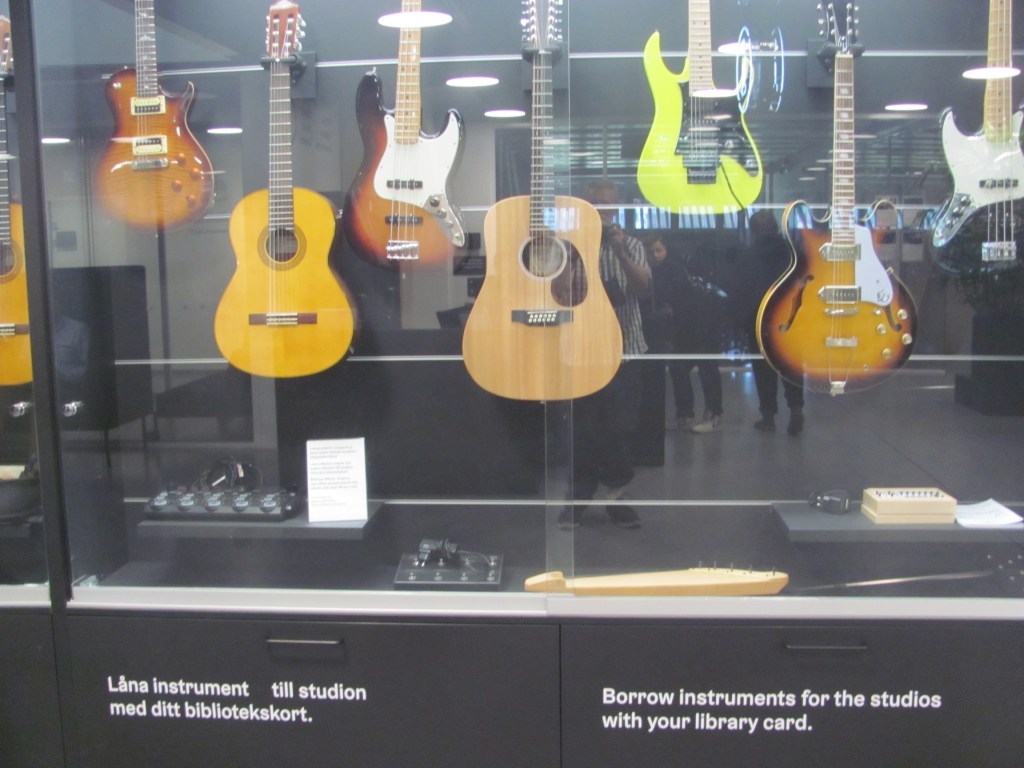

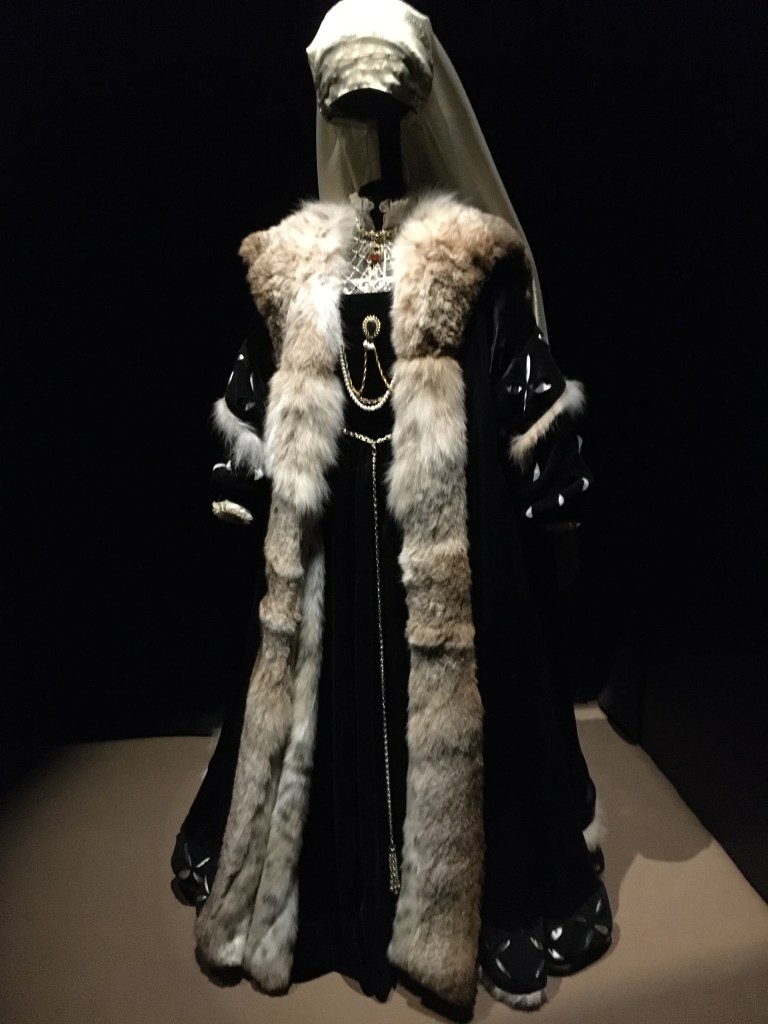

“The museum is dedicated to the Nazi and Soviet occupations of Estonia”, the girl at the desk tells us. “Much of it is told from the perspective of ordinary people. You can hear it all in your own language with one of these audio devices. Just select your language and press Start’.

We spend the next couple of hours listening to the stories of those who were deported to Siberia in the early stages of the Soviet occupation, those who fled Estonia to western countries, those who resisted Soviet occupation by hiding in the forests, those involved in the restoration of independence, and those now involved in building Estonia into a modern westwards-looking nation.

It’s intense, and at times harrowing, but also holds the promise of a better future. Afterwards, over a coffee, we discuss what we had learnt.

“Phew, you can really feel for the Estonians”, says the First Mate. “Two cruel occupiers, and having to make choices as to which one to support – if the Soviets, the Nazis will kill you; if the Nazis, the Soviets’ will deport or shoot you; if neither, then both will get you.”

“That’s the theme of a book I read over the winter”, I say. “When the Doves Disappeared, by Sofi Oksanen, an Estonian writer. It’s about the choices made by two cousins in Estonia under the Soviets and Nazis. One is fiercely patriotic and supports independence for Estonia, the other blows with the wind and works for whatever regime will allow him to survive and advance his career. There is a surprising twist at the end. It’s not an easy book to read, but worth it if you persevere.”

“It was interesting about the Phosphorite War”, says the First Mate. “I hadn’t heard of that before. It seems that the Estonian communist government in the 1980s, under pressure from Moscow, wanted to develop a mine to extract phosphorite in the north-eastern part of the country. Normal Estonians became concerned, not only for the detrimental environmental impact it would have, but also for the influence on the demographic balance of the influx of workers from other parts of the Soviet Union. When protests were organised, the government backed down. It showed the people for the first time that they had the collective power to change things, and paved the way for the downfall of the communist regime.”

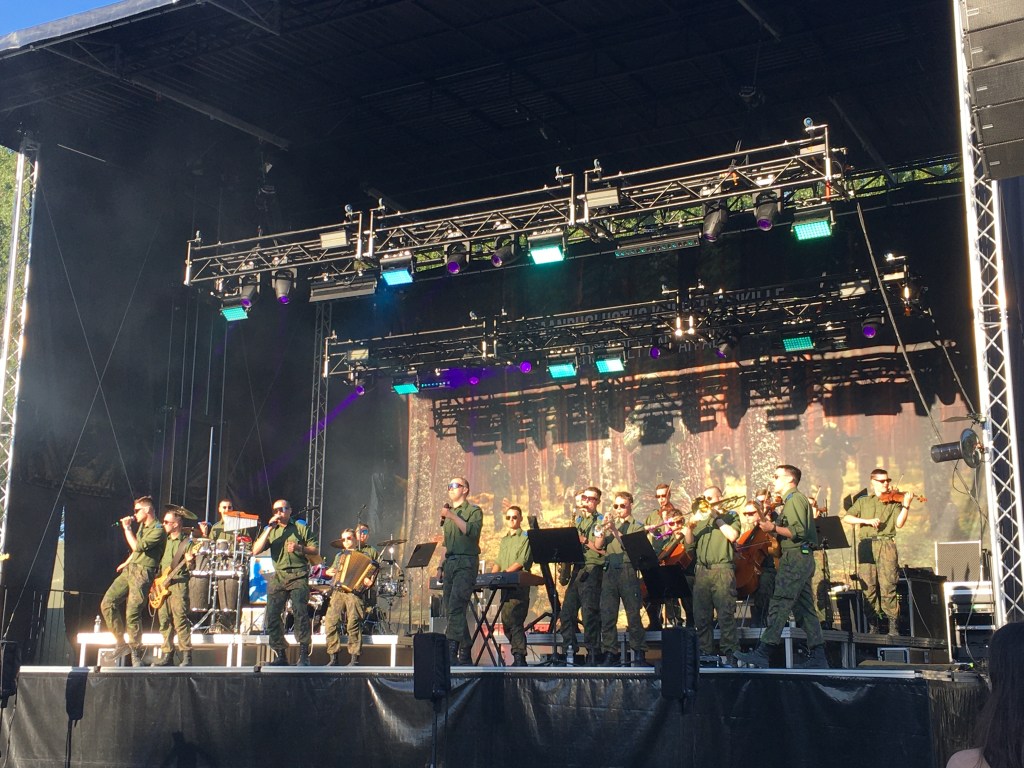

“It was also interesting about the Singing Revolution”, she continues. “How they formed a chain of people stretching from Tallinn all the way to Vilnius in Lithuania singing patriotic songs. It certainly got the message across to the Estonian communist government and Moscow that most people in the Baltic States wanted independence from the Soviet Union.”

“I thought that the bit at the end on what freedom means was thought-provoking”, I say. “One person was so ecstatic when Estonia became independent that he thought he could do whatever he wanted to. But after a few days, he realised that just freedom by itself wasn’t the whole story, and that along with it came the responsibility of doing something useful and contributing to society. You need to have a balance between freedom and responsibility. We don’t always appreciate that balance in the West.”