What on earth is that noise?”, says the First Mate.

I look at the clock. It’s 0800.

“I think that they have started on the bow”, I say. “I’ll go and have a look.”

We are back at Svinninge Marina where we are booked in for the repairs to the bow. Hans & Gisela have left to continue their journey home to Denmark.

I fall out of bed, rub the sleep from my eyes, pull my clothes on, and peer around the splash hood. A cheery face with a great bushy beard looks back at me from the bow.

“Hi”, the Beard says. “Sorry if I woke you up. I have just started to sand your bow back. But I am struggling to get a good angle on it. I think that we’ll have to lift her out so that I can get to it underneath. It’s just too awkward here. I’m worried that I might fall into the water.”

Images of a bedraggled, seaweed-entwined beard floating in the water appear briefly in my mind’s eye, but I quickly dismiss them.

“OK”, I say. “But is there enough time for us to have breakfast first?”

“Of course there is”, says the Beard. “I still have to go and book the crane.”

Later in the morning, Ruby Tuesday is lifted out and deposited on to a cradle. We find a ladder to get on and off her while she is there. We are just having lunch when there is a knock on the hull.

“I think that you had better come and have a look at this”, says Nicolas. Nicolas is the Beard’s boss.

It sounds a bit ominous. I clamber down.

“Did you hit a rock at some point?”, he asks.

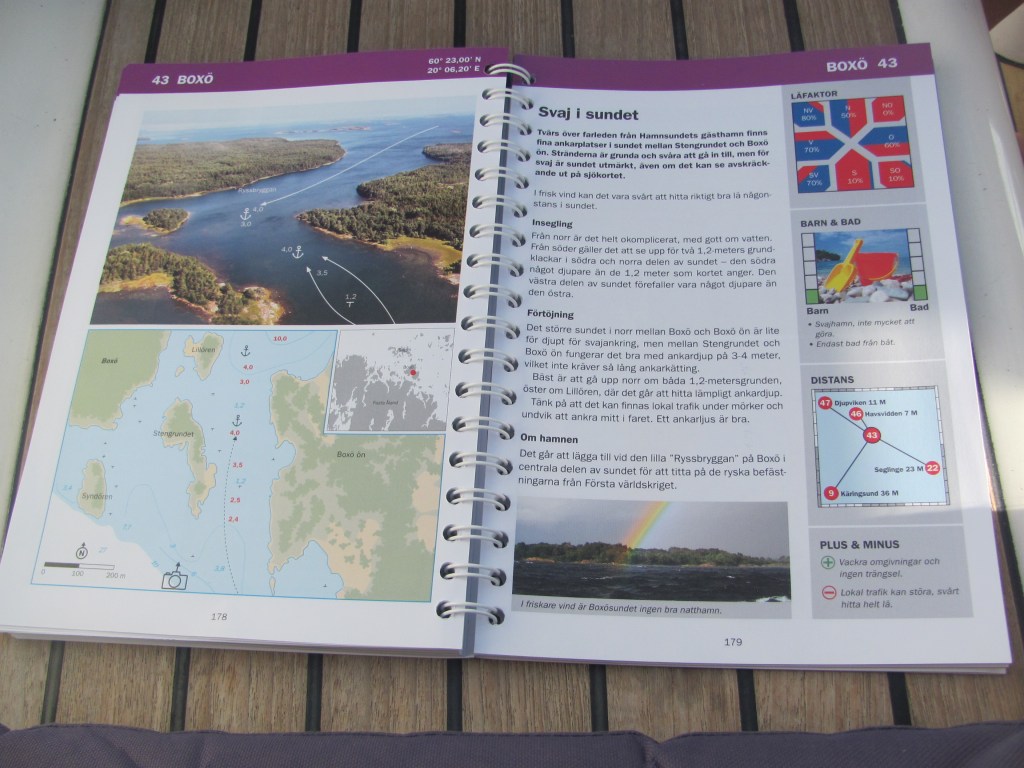

We had glanced off an uncharted rock previously, but there hadn’t been any leaks and I had dived under to check the keel and found nothing, so we had assumed that there had been no damage.

“You can see that small gap between the hull and the front of the keel”, says Nicolas. “ And there is a depression in the hull at the back of the keel. That’s a sure sign of an impact with a rock. It doesn’t look as bad as some that I have seen, but you really need to get it fixed. The boat is still able to be sailed OK, but if you were ever to hit another rock you never know what might happen.”

The First Mate and I have a confab.

“There’s no question that we have to have it fixed”, I say. “I’ll ask them if they could do it over the winter.”

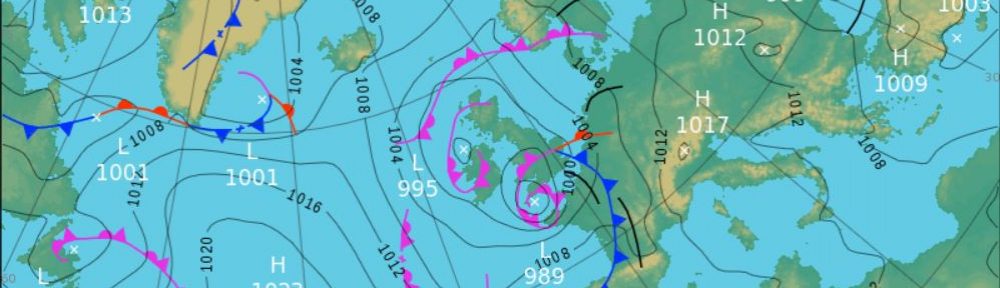

“Yes, of course”, says Nicolas in response. “But you will have to join the queue. We have several others lined up for similar repairs. Most people hit rocks at some stage or another. In fact, we have a saying that there are three types of sailor in Sweden, those that have hit a rock, those that are just about to hit a rock, and those that have hit a rock but don’t own up to it. It’s just one of risks of sailing in Sweden. But the good thing is that after we have repaired her, you’ll have a much stronger boat even than when she came out of the factory.”

We decide to leave her with them over the winter. It isn’t the marina we had planned to stay at, but that is of little consequence. Having her repaired before sailing her again is of prime importance. In any case, we find out later from several people that the company has the reputation of being the best in the Baltic for such repairs. People bring their boats from all over to have them seen to. That is some reassurance.

We take the bus and train down to the other marina where we have left the car, then spend the next few days preparing Ruby Tuesday for winter. All the normal jobs of taking down and stowing the sails, the cockpit tent and the splash-hood, and servicing the engine, are eventually completed. The First Mate starts cleaning and packing things inside.

“You’ll also need to cover her against snow”, Magnus advises us. “It needs to be quite steep so that it slides off. You can build a frame to support it out of this old wood here. Use what you like. When you are ready to put the ridge pole on, I’ll get some of the lads to lift it up. It’s too heavy for one person to do.”

Magnus is one of the employees of the repair company. It would be difficult to find someone more friendly and helpful.

I spend the next two days building the frame. Three A’s are soon constructed with their feet fastened securely to the side cleats. Magnus and his lads bring over the ridge pole and soon that too is fastened securely on top of the A’s. For good measure, I use screws and bolts to make sure that it is solid.

Then the covers from last year go on and are tied underneath the hull.

“That looks pretty good”, says Magnus. “I am glad that you didn’t tie the covers to the cradles anywhere. Some people do that, but occasionally the wind can be so strong it catches the cover like a sail and pulls the cradle away, and the boat falls over. You don’t want that to happen.”

“We still need to get the gas cylinders filled”, says the First Mate. “Let’s drive over this afternoon and do that.”

Filling gas bottles is a perennial problem. Despite being standardised in most other things, the one thing the EU has not yet managed to do is to standardise fittings on top of gas cylinders. Each country has its own system and many outlets will only fill bottles from their own country. We have cylinders we bought in Germany, but luckily have found an outlet that will fill those. The only thing is that it is on the other side of Stockholm.

“Sure, no problem”, says the man when we get there. “We can fill them. Bring them over to this shed.”

It’s time to leave. In the morning, I go for one last walk along the shore near the marina. The sun glows like a fireball, and the early-morning mist rises off the water’s surface. Islands hunker to either side, hiding their secrets. The masts in the marina sway gently from side to side, silhouetted against the scudding clouds of the sky beyond.

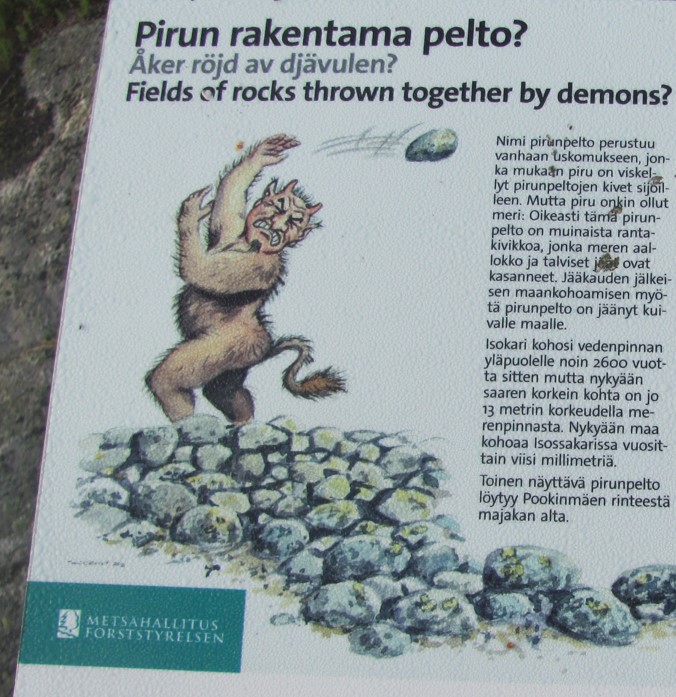

This is the Baltic, I think – sun, water, trees, islands and boats. I start to reminisce back over our voyage. Sailing to Åland, meeting our son, the rally and getting to know a new set of friends, the journey up to the Högekusten, the High Coast, and the many picturesque little harbours we stopped at on the way, the Högekusten itself with its impassive Skuleberget which we had climbed up, the long haul from Umeå to Luleå, the Sámi Museum in Jokkmokk, the beautiful Luleå archipelago, eventually reaching the famous buoy in Törehamn, the furthest north point in the Baltic that one can sail to.

The train trip to Rovaniemi to the Arctic Museum, then the beginning of the long trip back down the Finnish coast, often into the wind requiring us to take long tacks to get anywhere, but more than made up for by the quaint wooden towns that we had stopped at on the way, culminating in the UNESCO World Heritage site of Rauma.

And everywhere the traces of the empires and the rivalries of the great players in the Baltic – Sweden, Russia, Denmark, even Britain and France at one stage – that had come and gone over the centuries, some rivalries of which are still here in the present day. It had been a journey of discovery for us, learning of a part of the world that we had known little of before, and understanding a little more of why the current world is as it is.

Suddenly I feel a pang of sadness that we are leaving. As we followed the ancient seaways taken by the Vikings, the Swedes, the Danes, the Finns and the Russians, a closeness to the Baltic seems to be developing within us, one that can probably come only from discovering it by sail, the means of transport here for millennia. It feels familiar; almost, but not quite, like home.

A pair of swans fly overhead, the sound of their creaking wings waking me from my reverie. I tear myself away, and go and pack the last few things into the car. We finish our breakfast, say goodbye to Ruby Tuesday and Spencer, and start the long journey back to our other home.

But we will be back.