I awake in the early morning and lie listening to the lapping of the water against the hull. The wind seems to have gone round to the west, I think, and is driving small wavelets across the bay. I pull on my clothes and struggle on deck, rubbing the sleep from my eyes. Early morning mist arises from the water; the golden glow of the sun catches the mast, giving the fluttering flags an intensity of colour. There is no sign of life on the jetty or the town, everyone is still asleep.

We are in the harbour of the small town of Kaskinen, having arrived the night before after a lumpy sail down from Vaasa. The wind had been against us and we had had to take long tacks out to sea and back again to make any progress. We had managed it, but had arrived tired and hungry and had tied up at the newly built wooden jetty. A brief recce around the town had been unsuccessful in finding a place to eat, with the sole exception of a mobile takeaway van in the main square in front of the harbour. It was a Monday, and everywhere else was closed. We had bought a pack of fries and had taken it back to the boat to have with the leftovers from the previous day.

I decide to go for a walk and explore.

Kaskinen was founded in 1785, and was a planned town with all the streets laid out in a grid pattern. There were grand ambitions for it in the early days, and it was expected to grow into a bustling and wealthy port town centred around the import and export of tar and timber. But it never really took off, partly because it was on an island and bridges to the mainland took a long time to build, and partly because it was eclipsed by the larger nearby towns of Vaasa and Kristinestad.

Nevertheless, its old wooden houses give a quirky charm to it.

The apothecary is imposing. One wonders why a tower was necessary to dispense medicines.

When I get back, there is consternation on the quay.

“We’ve lost our cat”, wails the woman from the boat in front of us. “She wanted to go out, so we let her, and now she has disappeared. She has a GPS tracker around her collar, and it is showing that she is somewhere around your friend’s boat, but they have searched the boat for her and can’t find her. The only other place nearby is under the quay decking, but there is no way for us to get under there, so we will just have to wait for her to come out by herself.”

I have a mosey around the quay making meowing noises, but she is right – there is no way anyone could squeeze underneath and look for a cat, let alone rescue it.

“That’s the problem with having a cat on the boat”, moans the woman’s husband. “They dictate when we are going to leave rather than the winds, as with other sailors.”

“There was a similar occurrence when we were on Junkön near Lulëa”, says Gavin to us later. “We all had to get out and look for a lost cat, but it never turned up before we left. I can’t understand why people take their cats with them. It’s not fair on the cats.”

By the time we leave, the cat still hasn’t been found. There is nothing we can do except offer our condolences and hopes that it might still turn up. We cast off and head south.

The wind is on our nose from the southeast and blowing around 18 knots with gusts up to 26 knots. The sea is also rough, being whipped up by several days of southerly winds. We take a long tack close-hauled out to sea, then back in again. It’s an uncomfortable passage.

Eventually we reach the relatively sheltered waters of the approach to Kristiinankaupunki, and follow the marker buoys along a narrow channel not much more than two boat-widths wide, past the old harbour building, until we come to a road bridge. There is a marina to the right and to the left.

“We’ve just had a look at the marina on the right”, calls Gavin on the VHF. “There seems to be some construction work going on there. I suggest we go to the town quay on the left. There are limited facilities, but it has the advantage of being closer to the town centre than the other one.”

We tie up in the town quay. A man walking his dog along the jetty gives us a hand.

“Kristiinankaupunki is named after Queen Christiana of Sweden”, he tells us. “Kaupunki means city in Finnish. It is one of the towns founded by Per Brahe, like Raahe, back in the 1600s when this part was ruled by the Swedish. Its Swedish name is Kristinestad.”

After a cup of tea we go ashore to explore.

The town hall lies at the end of a stately avenue of trees.

“Come and look at this old water well”, calls the First Mate. “The wheel still goes round. Perhaps it still pumps water.”

It doesn’t.

A little bit further on is the Ulrika Eleonora church.

“The church was built in 1700 after the first one was burnt down a few years earlier”, the guidebook tells us. “It was named after the Queen Dowager of the time. Due to construction mistakes, the tower leans to the south. The story is that it is because the Russians tried to pull it down when they occupied it in the early 1700s, but weren’t successful.“

“The Russians don’t seem to be very popular”, says the First Mate. “Did you see the tiles on the roof? They are made of wood.”

On the way back to the boat, we see a Cittaslow sign.

“Ah, yes, I read about this”, says the First Mate. “Apparently the Cittaslow movement started in Italy in 1999 with the aim of slowing down the pace of city life. It focused on food quality at first, but extended to improve the general quality of city life through the use of space, reducing traffic flow, and opposing cultural standardisation. Kristiinankaupunki was the first Cittaslow town in Finland.”

“That explains the lack of traffic in the streets”, I say. “I thought it was quiet.”

Gavin and Catherine come over for a drink later in the evening. It’s starting to get dark earlier now that the summer is waning and we are sailing southwards.

“There’s a boat coming in”, says the First Mate suddenly, pointing. “You can see its lights, but not the boat itself.”

Sure enough, the red port side navigation light is visible in the darkness, moving slowly towards the marina. Suddenly it stops.

“I think that he might have gone aground”, says Gavin. “He looks too close to us to still be in the channel. The problem is that the marker buoys aren’t lit at night, so they are almost impossible to see. And he may not be aware that there two marinas. Perhaps we should try and contact him.”

I fetch the hand-held VHF radio from the cabin.

“The name of the boat is Celinda”, says Catherine. “I have just found it on MarineTraffic.”

I try to call Celinda several times, but there is no response.

“Perhaps we can signal to him with a torch”, says Gavin. “We could try and guide him in.”

The First Mate fetches our torch from the cabin.

“I think he is moving again”, says Catherine. “He must have managed to get back into the channel.”

Gavin goes ashore with the torch and waves it up and down. Sure enough, the boat slowly starts to move along the channel, and turns to come towards us. At last we can see the boat in the lights of the harbour. A woman is standing on the bow with ropes in her hands.

“Thanks so much for your help”, she says gratefully. “We missed the channel somehow and got stuck in the mud. The other marina didn’t look very inviting with all the construction work, and we didn’t realise that you could tie up at the town quay.”

We continue our journey southward the next morning. The wind is almost direct from behind, and there is not much of it. With both sails out in the conventional manner, the genoa flaps uselessly in the wind shadow of the mainsail. We manage a majestic two knots.

“We’ll never get there at this rate”, complains the First Mate. “Look! Saluté is heading off out to sea. Perhaps we should do that.”

Sure enough, Saluté is deviating from the direct route to try and get a better angle on the wind. The AIS shows she is managing five knots, but she will need to gybe back in again at some stage and will travel much more distance.

“We can pole out the genoa and goosewing”, I say. “They don’t have a pole, so they can’t do that.”

I rig a preventer on the mainsail to stop it from accidentally gybing, then pole out the genoa to windward. The wind catches both sails now and drives Ruby Tuesday forward at a respectable 4½ knots. What’s more, we can maintain the direct course easily, so have less distance to cover.

We eventually reach Rauma. Saluté has come back in from out at sea and ends up just in front of us, the same distance as when we set off in the morning. We tie up in the large Syväraumanlahti marina to the west of the town.

“We thought you had had enough of Finland, and had decided to head back to Sweden”, we joke with Saluté over a coffee.

“I couldn’t work out at first how you managed to sail directly downwind and still make a good speed”, says Gavin. “Then I realised that you must have poled out your genoa.”

“It was amazing how the different strategies ended up with the boats in the same relative positions after a whole day’s sailing”, says Catherine. “Almost to the metre.”

In the morning, we unload the bikes and cycle into town.

Although a Franciscan monastery and Catholic church had existed from earlier times, Rauma only became a town in 1442. Its prosperity came from its maritime activities, but it is also famous for its lace-making and paper industries. Latterly, it has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage site for its exquisite old wooden buildings in the town centre. Like many of the other wooden towns along the Finnish coast, the town was burnt down and rebuilt several times. The present old town dates back to the 17th century.

“Look at these wooden sculptures in the stream”, says Catherine, as we come to the town centre. “Three women looking apprehensively at the frog prince. That’s original.”

We learn later that it is the work of Kerttu Horila, a sculptor who lives in Rauma, and who has made several figures which are dotted around the town.

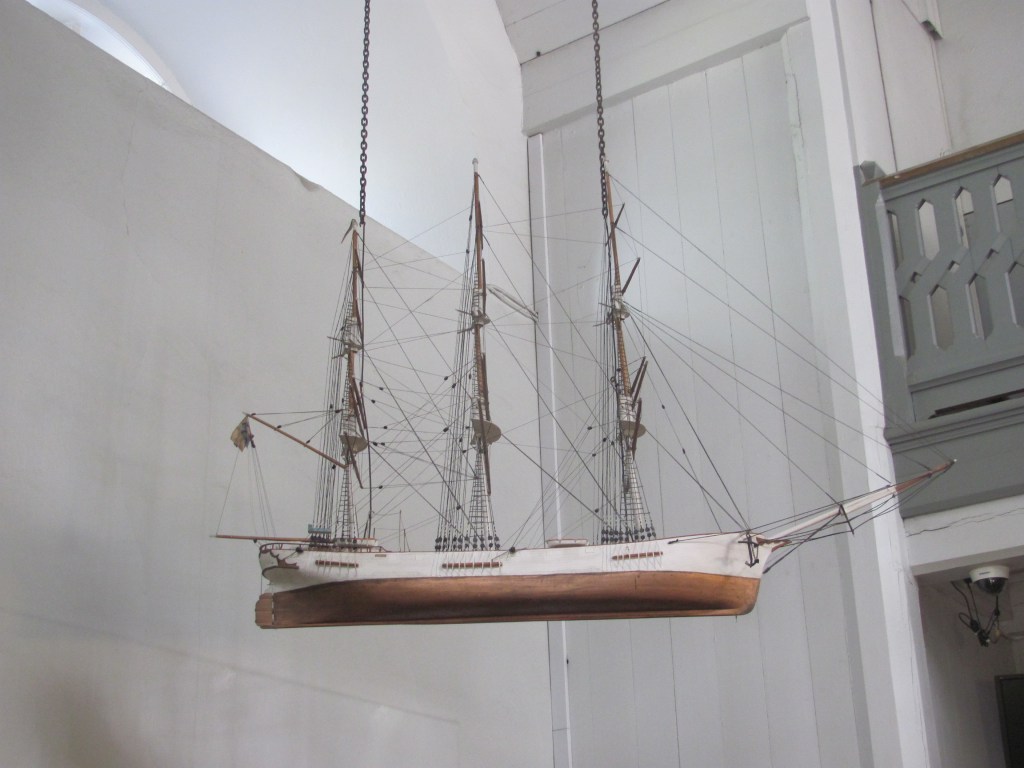

“You can see the maritime influence on the town”, says Gavin. “Look, even the Catholic church has a model ship hanging in the entrance, just like the Gavle churches that we saw in Sweden.”

“I’m getting a bit peckish”, I say. “Let’s find somewhere to have lunch.”

As we walk back to the market place, an open top American car passes us.

“They certainly love their old cars”, says the First Mate. “I have seen several like that around.”

We find a restaurant near the town centre and peruse the menu.

“I can recommend the lapskoussi”, says the waitress. “It’s a traditional Finnish sailors’ dish. It doesn’t look anything special, but it tastes delicious.”

Four identical plates of lapskoussi arrive. It turns out to be a mixture of beef, potatoes, onions, carrots, and various other vegetables, all boiled and mashed together with different spices added, and served with melted butter on top. Sure enough, it doesn’t look particularly exciting.

“Well, that was certainly delicious”, says the First Mate, folding her knife and fork and sitting back contentedly. “And also very filling. We definitely won’t need to cook any dinner tonight.”

We decide to split up and explore different parts of the town, and meet up later. The First Mate and I end up at the Maritime Museum.

“Do you want to have a go on the simulator?”, asks the museum attendant in one of the rooms. “You can pretend you are the skipper of a fishing trawler coming back home to Rauma harbour after a successful fishing trip.”

I take the steering wheel.

“I’ll put the throttle on medium speed”, she says. “You don’t want it too fast, especially coming into a harbour.”

It is a lot slower to respond than Ruby Tuesday, and nothing seems to happen at first when I rotate the wheel. Then the boat begins to turn faster and faster. I rotate the wheel in the other direction, but again it takes some time to respond, then it turns faster and faster in the other direction. Eventually, I learn to anticipate what the boat will do in a half a minute or so, and manage to control the yo-yoing from side to side enough to enter the harbour without hitting anything.

“You’re pretty good”, says the attendant. “It’s almost as if you have done it before.”

“I have”, I answer. “I did it yesterday in our boat. We are sailing around the Baltic and are here for a couple of days.”

In the next room, I read of the Finnish seamen who were interned in Britain during WW2. Because Finland had decided to fight on the side of Germany against Russia, Britain had declared war on Finland in 1941, so any Finnish crew on ships were considered the enemy and were rounded up and interned on the Isle of Man. It seems they were a rowdy lot, and fights broke out between those that supported Finland and Germany, and those who supported Britain and the Allies. When stabbings started, the authorities had to separate them into two camps. Several of the pro-British Finns joined the British merchant navy.

A little known piece of wartime history that I had been totally unaware of.

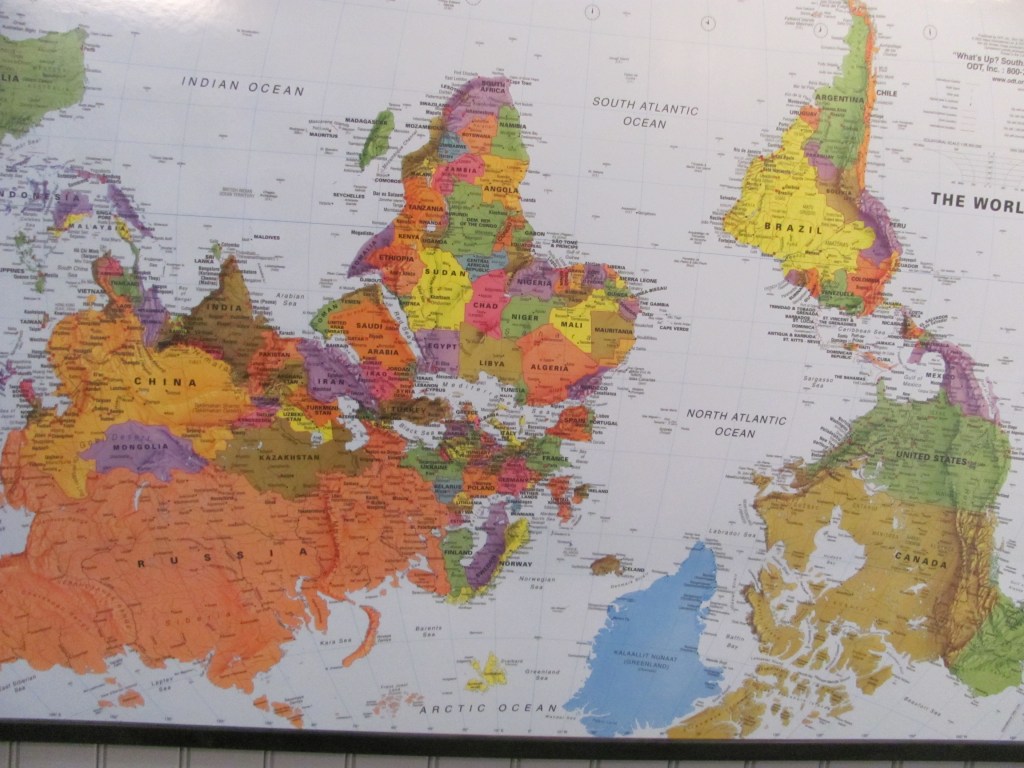

“Here’s an interesting view of the World”, says the First Mate as we leave. “The Finnish view.”

Next up is Marela, the home of the wealthy ship-owning Granlund family in the centre of town.

“Wow!”, says the First Mate. “The rich certainly knew how to live.”

We meet Gavin and Catherine for a coffee.

“Apparently you can get a good view out over the town from the tower on the hill”, says Gavin. “We can cycle over there.”

We puff our way to the top of the hill. The tower is closed for the winter.

“What a bummer”, says Gavin. “Everything closes so early here.”

“It’s because a lot of the places are staffed by volunteer university students”, says a woman passing. “Now they have all gone back to university, so they have to close them.”

On the way back down again, we notice an intriguing sculpture of doves escaping a series of concentric rings.

It is a memorial to those that had to flee the Karelian region in the Continuation War, says the plaque underneath. When the Russians invaded Finland in WW2, thousands of people living in that part of the country had to be evacuated and were resettled in other parts of Finland, as they didn’t want to live under Russian rule.

“I can understand how they must have felt”, says the First Mate. “My mother also had to flee their home in East Prussia at the end of WW2 to escape the advance of the Russians. She was only eleven years old at the time.”

“They were tough times”, I say.