The six women are led out to the wooden platform. I clutch my mother’s dresses tighter. I don’t know what is going to happen, but I know it is bad. The women are guided to the structure on the platform with six ropes hanging from it. Under each there is a box which the women are made to stand on.

“Mother, what’s happening?”, I ask my mother in a shrill voice. “Why are those women being made to stand on those boxes. And what are those ropes for?”

“My little one”, she says. “They are evil women. They confessed to the governor that had attended a Witches’ Sabbath and made a pact with the Devil. Now they have been sentenced to death for their crimes. Good riddance, I say.”

I watch with morbid fascination as one by one, a noose at the end of each rope is placed around the women’s necks.

“Mother, mother”, I cry in alarm. “One of those women is my friend John’s mother. Surely she isn’t a witch? She is always so kind to me. The governor must have made a mistake.”

“No mistake”, replies my mother. “The governor was guided by God, and God can see into every person’s heart and what is going on in it. He must have been able to see that John’s mother had evil there, despite appearing to be kind on the outside.”

There is a fanfare of trumpets and the Governor of the Castle arrives with his retinue. I had already seen him before several times as I tended my father’s sheep, cantering out of the Castle gates on his horse as he went about his business. He speaks something to the women, but his voice is low and I can’t make out he words. They begin to wail in terror.

“I am not a witch”, cries John’s mother. “I have been a good woman all my life. I have had nothing to do with the Devil.”

There is a sudden shout, and a man standing at the side of the platform steps forward. One by one, he kicks away the box each woman is standing on. The cries of terror cease, the women’s bodies convulse, then all is still. The watching crowd lets out a loud cheer. I feel I want to be sick, and try to run, but my mother holds me tight.

“It’s good that you have seen these evil women die”, she says, with little sympathy in her voice. “Let it be a reminder throughout your life to serve God and not the Devil, otherwise a similar fate may befall you.”

“What do you think of this?”, says a voice behind me. I turn. It is one of the Governor’s men wearing his helmet.

The voice seems somehow familiar. It takes me a few seconds to realise that it is not the Governor’s man, but the Cabin Boy, wearing a steel helmet put there for visitors to try on.

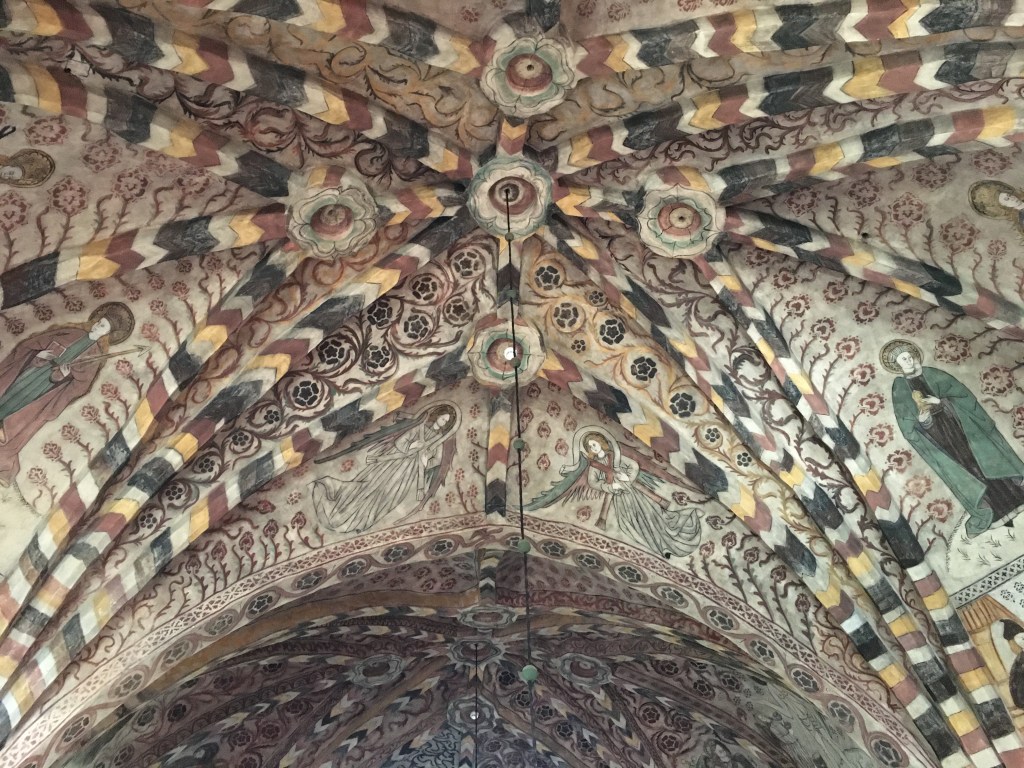

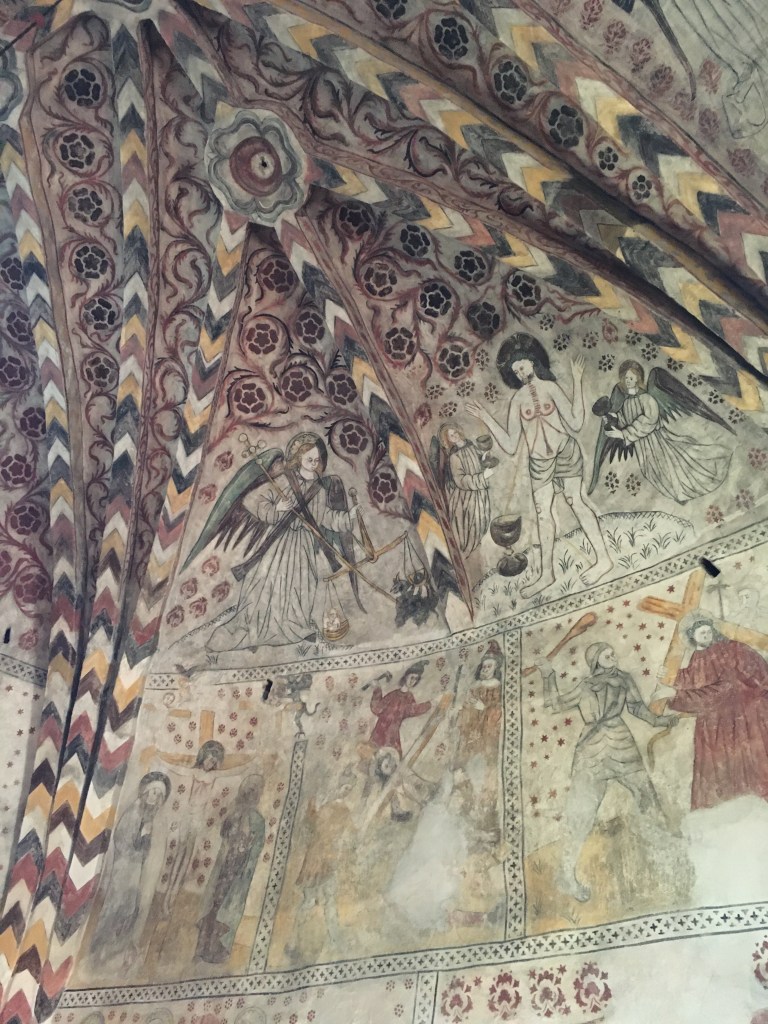

We are in Kastelholm Castle, and I have been imagining what is might have been like at the end of the Kastelholm witch trials in 1668. Local women accused of witchcraft were brought to the castle where they were forced to confess to the Governor of attending a witches’ Sabbath and making a pact with the Devil. They were then tortured to reveal their accomplices before being hung.

“Hardly a fair trial”, sniffs the First Mate. “At least we have made a bit of progress in justice since then. Come on, let’s go and have an ice-cream.”

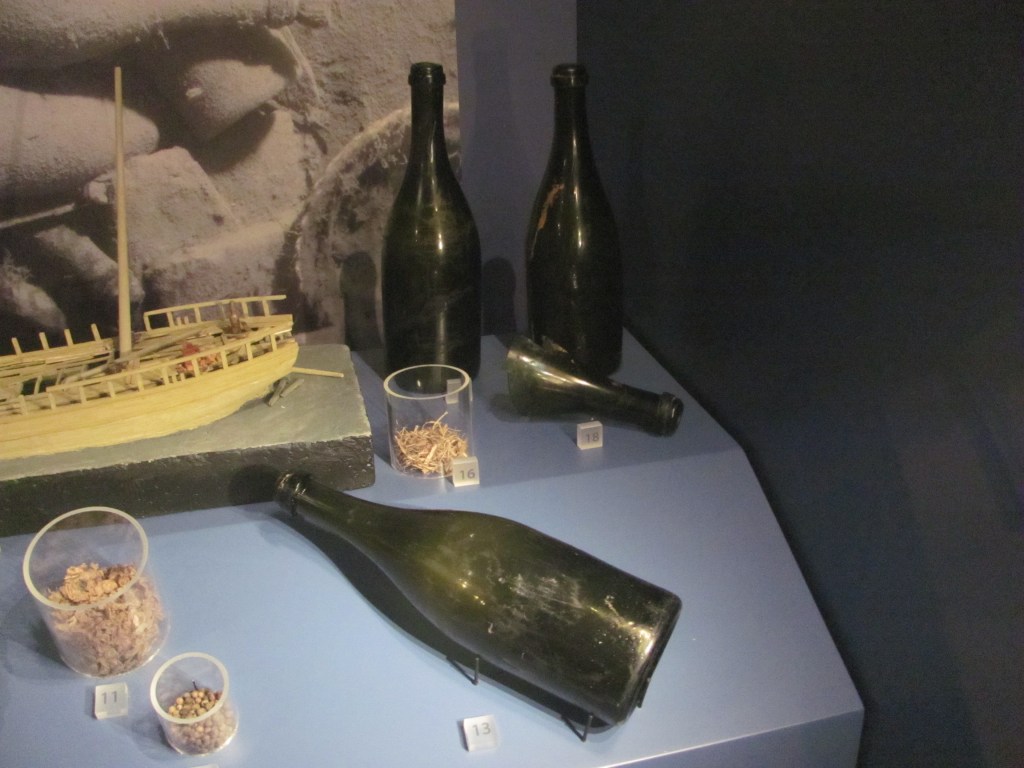

We had visited the Åland Gin Distillery that morning, where different herbs and spices are added to the base spirit distilled from grain elsewhere to give a distinctive Åland flavour. We had then been treated to a gin tasting and a lunch of traditional Swedish meatballs and accompaniments.

“Those were the best meatballs I have tasted in a long time”, says the First Mate, sitting back in her chair contentedly. “Far better than those from a leading furniture retailer I could name.”

After lunch, we had sauntered over to the Castle opposite. A timeline just inside the entrance explained that it had been built in the 1380s as a symbol of Swedish power and prestige, and that King Gustav Vasa had hunted in its grounds. It was then captured by the Danes in 1505, but recaptured by Charles IX of Sweden in 1599. Recently it has been restored and attracts many visitors each year.

“It has certainly seen a bit of history”, says the Cabin Boy as we leave. “Did you read that one of the Swedish kings John imprisoned his own brother Erik in there for a while?”

This was the same John III that had been imprisoned by his brother Erik XIV in Gripsholm Castle in Mariefred that we had seen last year, but had returned the favour when he was freed by imprisoning Erik. That hadn’t been all though – Erik died insane, probably from arsenic poisoning by his brother.

“The Windsors aren’t the only Royal Family that are a bit dysfunctional”, I say.

In the evening, we meet for drinks at the dockside bar. I find myself sitting next to Simon. We strike up a conversation on the Vikings.

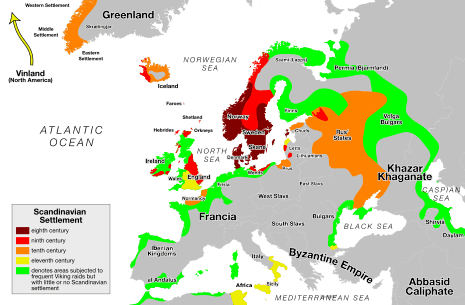

“The one thing that I don’t understand about the Vikings is what motivated them to expand throughout Europe”, he says. “Look at where they went – much of Britain, France, Spain, Italy. They even got as far as Iceland, Greenland and North America.”

“Yes, and in the other direction they migrated down the Volga and founded Kyiv in present day Ukraine”, I say. “They ruled a large state called Kyivan Rus’, which was the origin of the Russian people.”

“True, but what made them want do it?”, persists Simon. “Why didn’t they just stay at home in Scandinavia? I have read that overpopulation of the available land was the reason, but I don’t buy that. Sweden has lots of land, and Denmark is very fertile.”

“I don’t think there was a single reason”, I say, trying to remember what I had seen in the History Museum in Stockholm. “Shortage of land was certainly a factor for the Vikings from Norway. They expanded westwards to Britain, Iceland, Greenland and the America to colonise new land. But for the Vikings from Sweden, trade was the main reason. They were particularly keen on silver and traded to get hold of it. And it was mostly the Danish Vikings who did all the raping and pillaging that terrorised Europe at the time.”

“And they had the technology to do all that”, says Simon. “The longboat, I mean. They were fairly robust sea-going vessels. But was there also something in their psyche that made them want to be so ruthless?”

“I suppose the Norse religion contributed to that”, I say. “It glorified violence – only those who died in battle would go to Valhalla. Those who didn’t would go to Hel. That’s a pretty powerful incentive. And their lack of respect for Christian monasteries and the like – the rich pickings they could easily have by purloining the treasures so conveniently collected and stored for them in one place by defenceless monks, would surely be another.”

It’s almost the end of the rally. We slip the lines early the next morning, and head across the Lumparn crater for the Lemström Canal with its swinging bridge. It opens on the hour ever hour between 0900 and 2200. We make it for the 0900 opening and are quickly through to the bay east of Mariehamn. We tie up in a box berth at the Mariehamn East marina.

“I feel a bit sad that it’s all over”, says the First Mate. “I have to say that I have really enjoyed it. Great weather, great scenery, and great people. What more could we ask for?”

In the afternoon, we ‘dress’ the boat. This involves stringing a line of signal flags from the bow to the masthead and down to the stern.

“You can’t put them in any old order”, says Bob in the boat next to us. “There is a specific order that they have to be in so that you don’t inadvertently send a message you don’t want to. I’ll email it to you.”

We spend the next hour or so linking our code flags together, and hoist the ends of them to the top of the mast with the spare halyards.

“Oh no”, says the Cabin Boy as we stand and admire our work. “There’s one flag left in the bag. I’ve left out the letter ‘L’. What should we do? It’s a bit of a faff to get them all down again and put it in.”

“Don’t worry”, I say. “No one will notice.”

No-one does.

“It all looks very colourful”, says the First Mate. ”It’s a pity we can’t keep them there all the time as we sail along.”

“The rules say they are only supposed to be used in harbour for special occasions”, I say. “Not when sailing. I assume because they might get tangled up in the sails.”

In the evening, before the final Rally dinner together, we gather to say thanks to Andy, the Rally leader, for his wonderful organisational skills in making everything run so smoothly.

It’s been a great ten days, and we are all a bit sad to see the end of it. But it’s not goodbye to everyone, as several of us plan to continue on to the High Coast area afterwards. Not necessarily together in a rally or exactly at the same time, but we do agree to keep in touch. Bob sets up a WhatsApp group.

“We can swap tips and photos with each other”, he says. “And arrange to meet up if we are not too far away.”

Early next morning, we say goodbye to the Cabin Boy. It’s been great to see him again, but the time with him has flown too quickly. A taxi arrives and takes him to the airport for him to begin his long journey back to Australia.

“I’m going to miss him”, says the First Mate, wiping a tear from her eye.

“Me too”, I say.

In the afternoon, I take the bus out to the Bomarsund Fortress. We were to have stopped there on the rally, but because of unfavourable winds, we had had to divert from that plan.

The newly constructed Visitors’ Centre gives a good overview of the history of the fortress.

“As a result of the Finnish War between Sweden and Russia, Finland and Åland were ceded by Sweden to the Russian Empire in 1809”, a video tells me. “But Russia needed to contain Sweden and maintain control over the Eastern Baltic, so in 1830 they began building a large military fortress at Bomarsund. The main fort contained barracks, offices, bakeries, a prison, and an Orthodox church. Nearby, a sizeable town called Skarpans developed to support the fortress.”

The Åland islanders got used to the Russians being in control, and life continued much the same as it had done under the Swedes. Suspicions lurked, however, and stories circulated that the Devil himself attended parties and even danced with the minister’s wife.

“Then in 1853, the Crimean War between Russia and the Ottoman Empire began”, a nearby panel says. “Britain and France decided to take the side of the Ottomans to contain Russian expansion to the Middle East. The conflict spilled over into the Baltic when the French and British attacked the half-completed Bomarsund fortress in 1854.”

“The Russians believed that an attack by sea from the west was not possible due to the narrow approach routes being too restrictive for sailing ships”, another video tells me. “So they had not fortified that part of the castle very well. But the British had steam ships which were much more manoeuvrable than sail. Consequently, they were able to come close and maintain a continual bombardment on the fortress without sustaining much damage to themselves. Eventually the Main Fort was largely destroyed, and the Russians surrendered. The victorious British and French offered the captured fortress to the Swedes, but they didn’t want it for fear of provoking the Russians, so it was blown up. “

I take the 4.5 km walk around the planned periphery of the whole fortress. Only two towers were ever completed, their cannon still forlornly pointing in the direction that the enemy never came from.

I end up back at the ruins of the destroyed Main Fort, and try to imagine what it must have been like for the soldiers defending it from the continual bombardment from the navy ships in the bay to the west. With limited large guns of their own on that side and with no time to move any from other parts of the fortress, all they would be able to do was suffer stoically, and hope that they wouldn’t be in the way of an incoming cannon ball. All in the interests of remote men in Moscow, London and Paris playing the Great Game to balance each other’s power so that no one country in Europe would become too dominant.

“The battle of Bomarsund had far-reaching consequences for Åland, as in the resulting peace treaty it was agreed that Åland should be demilitarised, which it remains so until this day”, I read in the tourist brochure on the bus ride back again. “Also, after Bomarsund was destroyed, it led to the establishment of Mariehamn as the capital of Åland in 1861.”

“A bit like a huge game of chess, wasn’t it?”, says the First Mate later. “I feel sorry for the poor soldiers and common people that got killed through no fault of their own.”