“There’s a rock concert on for the next three days”, says the captain of the boat tied up in front of us. “Rauma Rock. It’ll be really loud. We were here last night, and we could hardly hear ourselves think until about four in the morning. But the music was good. There will be even more boats coming tonight. It will be packed.”

We are in the tiny harbour of Andalsnes near the top of Romsdalfjord. There had been no berths free when we had arrived, and we had rafted up to another small yacht while we decided what to do. It was then that we had noticed that a large stage had been constructed on the quayside, with the twanging of guitar strings warming up emanating from it.

“I don’t really want to be kept awake all night”, says the First Mate. “I am at that age where I need my sleep. But it would be somehow nice to hear some of the music.”

“Me too”, I say. “My hearing is bad enough as it is with old age, without finishing it off completely. Why don’t we go and anchor a little bit further up, where can still hear the music, but it isn’t quite so loud? And we wouldn’t have to pay either!”

The last sentence is the clincher.

“Good idea!”, she says. “But let’s have a quick look at the town first to see what it is like.”

The First Mate explores the town centre, while I take a walk down to the Rauma river running through it.

“Well, the town was pretty average”, she says, when we meet again. “I didn’t find it very inspiring.”

Later we motor a little further along the shoreline of the fjord and drop the anchor.

“Perfect!”, says the First Mate as we sit on deck with our glasses of wine watching the gondolas taking their passengers to the top of Mount Nesaksla, and listening to Rauma Rock getting underway. “That’s much more enjoyable.”

“Andalsnes was one of the places that my great-great-grandfather visited”, I say. “Or at least Veblungsnes, which was the main settlement in those days. Since then, Andalsnes grew to be a town, while Veblungsnes remained a village. The Rauma river divides the two. In his letters he talks about the striking wonders of the Rauma river, but he says that he doesn’t have time to describe them.”

“The guide book says that the Rauma is famous for its salmon fishing, the emerald-turquoise colour of its water, its towering mountains, deep gorges, and sheer cliffs, and its waterfalls at Vermafossen and Slettafossen”, says the First Mate. “It was the inspiration for scores of Romantic artists, writers and explorers.”

“It would be nice to go and see it”, I say. “But we’ll never get in to the harbour now with all the boats that have been arriving.”

“We’ll have to come back another time”, says the First Mate.

In the morning we set off back along the Romsdalfjord. I keep a sharp eye out for sea-eagles.

Far above, wheeling on the updraft from the cliffs, Eira looks down on the waters of the Romsdalfjorden. She doesn’t come here often these days, instead spending most of her time with the other sea-eagles on the islands and skerries at the mouth of the fjord where the fish are plentiful. But from time to time she likes to revisit her birthplace and recall the stories that her father Clew and her mother Aran used to tell of Cuillin, the last of the great sea-eagles of Skye, who had flown alone from there to Romsdal to save her kind. And of her daughter Mourne who had returned to Skye with her motley collection of vagrants to repopulate those islands.

Out of the corner of her eye, she sees a boat heading for the tip of Okseneset and the shapes of two humans. They won’t be able to see her, she is too high and against the sun. She does not fear them in the same way that her parents had done – the Doom that she had heard in the old stories had passed now and there seemed to be a new understanding between her kind and the humans.

And yet, from time to time there was a niggling feeling in the back of her mind that the Doom had not gone completely. To be sure, few of the Romsdal eagles died these days by being shot or poisoned, but she had heard that there were increasing numbers flying into the high towers with rotating blades that had appeared in Møre og Romsdal. And then there was the rumour that was going around the Pairs that the eggs being laid were hatching earlier in the year, there seemed to be more rain than she remembered in her younger days, and the weather appeared to fluctuate more between extremes. But surely humans couldn’t be blamed for that, could they? Clever as they seemed to be, they were just too small and insignificant to be able to change the forces of Mother Nature herself, the might of the winds and rain sweeping in from the Atlantic, the strength of the sun’s light bringing warmth and life to the earth. Surely only Haførn, the mother of them all, had the power to do that …?

As she circles, she sees another sea-eagle gliding over the island of Sekken. She recognises from his flight that it is Arvid, her mate. She dips her great wings and flies to meet him, the humans in their small boat disappearing from her view.

“Are you day-dreaming again?”, the dulcet tones of the First Mate interrupt my reverie.

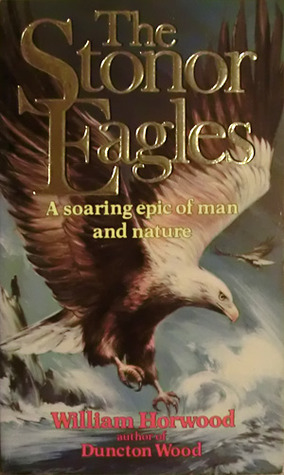

“I was hoping to see a sea-eagle”, I say. “I was just thinking of the book I re-read over the winter – The Stonor Eagles by William Horwood. It’s about how sea-eagles went extinct in Scotland in the 1930s through the farmers shooting them to stop their sheep from being attacked, and how they were reintroduced in the 1970s from Norway. Romsdal was one of the areas that they brought them from. I read somewhere that you do see them here.”

“I imagine that there would be more down towards the ocean”, says the First Mate. “That’s where the fish are, after all.”

We arrive at the town of Molde on the northern shores of Moldefjord, and head for the small municipal marina. It’s sweltering. A woman in a tank top and shorts helps us tie up.

“That’s my boat just in front of you”, she tells us. “I live on it throughout the summer and then go back to my apartment for the winter. It’s kind of like a summer cottage, but on the water. I don’t sail far – there are enough beautiful places to visit around here.”

After a cup of tea, we decide to explore the town centre.

“It’s a pity we weren’t here a couple of weeks ago”, says the First Mate. “We could have gone to the Jazz Festival. They have one every year.”

“Look, here’s the Salmon Centre”, I say, pointing to a building in the town square. “We should go and have a look at it.”

“It’s free entry”, says the girl at the reception. “And that includes a free sample of raw salmon, which you can use to make your own snack with taco shells and various dips.”

For the next little while we are absorbed in creating our own culinary delights, learning about the life cycle of the salmon from ‘roe to plate’, how the cages are made and installed, and how it is becoming more sustainable, including ways to prevent farmed salmon escaping to mate with wild salmon and weakening their gene pool.

“That was fascinating”, I say, as we emerge. “I now know more about salmon than I ever thought I would.”

“Yes, it was”, says the First Mate. “Come on, let’s have a coffee and cake. Look, there’s a nice looking place over there. We can sit outside. You grab a table, and I’ll go and choose the cake and order.”

“Earl Grey tea for me, please”, I say.

“Well, this is a nice little watering place”, says the minister to his companion as they sit down. “I enjoyed the walk around the town this morning. Such lovely weather. And what a nice smell from all the flowers they grow.”

“Molde is famous for that”, responds Mr Fairlie. “Especially the roses. Their fragrance is everywhere.”

“I had a look at the new church”, says the minister. “Apparently the old one burnt down four years ago, and they just finished building a new one last year. I must confess that I like the look of the old wooden one I saw in pictures better than the new one. All red-brick now.”

“I suppose it will be more fire-proof, at least”, says Mr Fairlie. “That’s always the problem with wooden buildings in this part of the world. It’s only a matter of time before they get burnt down.”

“And I have to say that I was impressed at the beautiful resting place of the departed here”, continues the minister. “With its small mounds of earth crowned with the loveliest flowers. The graves are tended with the fondest care and mothers come and sit by their loved ones’ dust for hours, with a book in hand or plying the needle, engaged on some piece of useful or fancy-work.”

“Here we are”, says the First Mate, bringing a tray with the coffee, tea and a cheesecake. “What a nice spot. We can sit and watch the boats coming and going. But why are you putting in pictures of the cemetery? That’s a bit macabre.”

“My great-great-grandfather went to see it”, I say. “I thought I should too. He seemed to like that sort of thing.”

“You seem to be enjoying this cruise, at least?”, says Mr Fairlie.

“Immensely, but I have to admit I never feel relaxed on a boat”, says the minister. “Ever since I lost my younger brother Andrew at sea.”

“I didn’t know you had a younger brother”, says Mr Fairlie. “What happened?”

“He was on his way out to New Zealand”, replies the minister. “Another brother of ours, James, was already out there farming near Dunedin, and Andrew was intending to join him. He was a minister like myself, and had been in Canada but had fallen out with some of his superiors there. I don’t know what about. He always liked his drink and was a bit of a hothead, so maybe it was something to do with that.”

“So he was looking for a fresh start in New Zealand?”, asks Mr Fairlie.

“Yes, that sort of thing”, says the minister. “He was on board a ship called the Burmah sailing from London to Lyttelton. It seems it might have been overloaded, as in addition to the passengers, it was carrying a consignment of high-class horses and cattle. But it never arrived in Lyttelton. Another ship fourteen days out from New Zealand reported passing it in the Southern Ocean, and also that they had seen icebergs in the area at the time. So we are guessing that the Burmah must have hit an iceberg and sank.”

“What a story”, says Mr Fairlie. “Your poor brother. To have all his hopes dashed when he was so close to realising them. It’s a salutary reminder of the perils of sea travel.”

“Yes”, continues his companion. “But the story doesn’t end there. One or two years later some ship’s timbers were washed up on a beach to the south of Dunedin with the letter ‘B’ written on one of them. The supposition at the time was that it was from the Burmah.”

“And it’s sad to think of your brother James already in New Zealand waiting patiently for Andrew to arrive”, says Mr Fairlie. “Looking forward to seeing a member of his family again, then the slow realisation each passing day that his brother may not be coming. But never really knowing for sure.”

“No closure”, says the First Mate, as she takes the last of the cheesecake. “As we might say today. It’s a poignant story. But I can understand how your great-great-grandfather felt about the sea. I never feel at ease with it myself.”

“Who does?”, I think to myself.

In the evening, we sit on deck and eat our dinner. Suddenly three men from one of the neighbouring boats come over.

“We’ve been composing songs to amuse ourselves”, one says. “We’ve made one about your boat. We wondered if you might like to hear it?”

He presses the Play button on his portable stereo. A Scottish folk song plays.

Ruby Tuesday

She was born on the Clyde where the river runs wide,

Painted red like the fire of the morning tide.

With her sails full of dreams and her heart on the sea,

Ruby Tuesday’s the name, and she’s calling to me.

From whisky shores and bagpipes’ cry,

She’s chasing sunsets, kissing the sky.

Oh Ruby Tuesday, rolling with the waves,

From Scotland to Molde, where the fjord light plays.

We’ll sing and we’ll dance as the moon shines through,

On a deck full of laughter and a sky so blue.

The gulls sing along, and the wind hums a tune,

As we sail through the night by the light of the moon.

There’s a fiddle on board, and the stories run wild,

Of whiskey and freedom and the heart of a child.

She’s got no fear of the stormy skies,

‘Cause Ruby’s a queen with fire in her eyes.

Oh Ruby Tuesday, rolling with the waves,

From Scotland to Molde, where the fjord light plays.

We’ll sing and we’ll dance as the moon shines through,

On a deck full of laughter and a sky so blue.

Raise your glass to the Northern light,

We’re sailing strong through the soft midnight.

Every mile that we leave behind,

Brings us closer to peace of mind.

Oh Ruby Tuesday, you’re my guiding star,

From Scotland to Molde, no journey’s too far.

With the wind in your sails and the sky so true,

Every song that I sing, I’ll be singing for you.

It’s brilliant. Not completely factually accurate, but who cares about details? We’re touched.

Realy lovely song! 😉

Interesting about eagles 🦅 and your great great grandfather! 😏

LikeLike