“It’s incredible the amount of work that must have been done to drill this tunnel through the mountain”, says the First Mate. “And to think that we are going right underneath a glacier.”

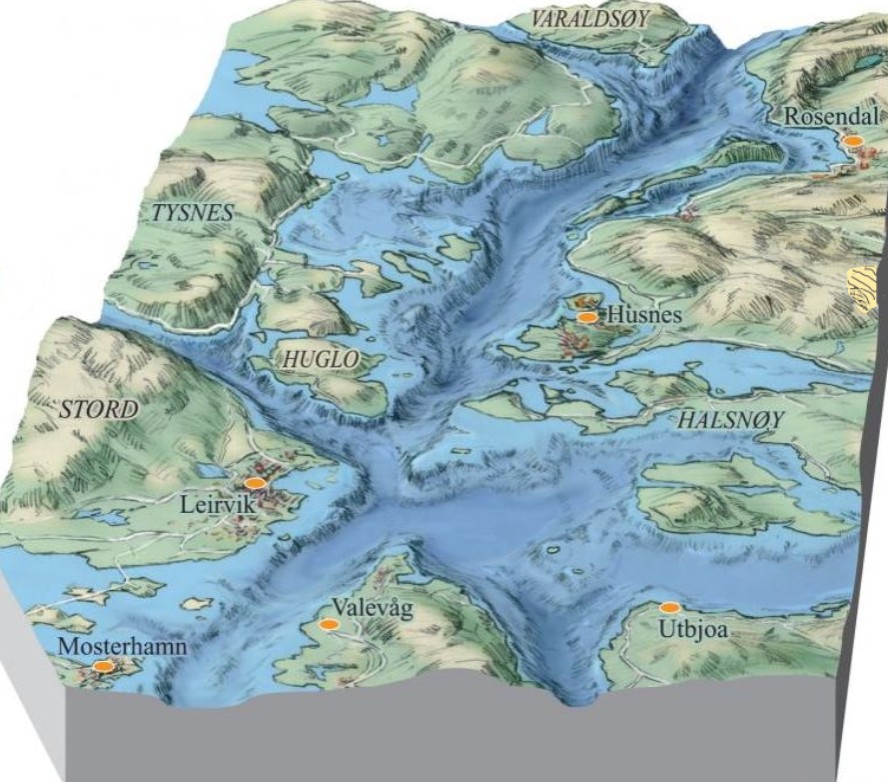

We are on the bus to the town of Odda at the head of Hardanger fjord. We had left Haugesund the day before, and had had a pleasant sail with favourable winds up the Hardanger fjord, arriving in the picturesque village of Rosendal in the evening. This morning we had caught the bus and snaked our way along the coastline until the mountain sides had become so steep that the road had had to take other measures to continue.

“Yes, the Folgefonna Tunnel”, I say. “It’s more than 11 km long. That’s a lot of rock to move.”

We eventually emerge from the tunnel, our eyes blinking as they adjust to the light. Initial impressions are not positive. The first thing we see is a huge industrial complex on a small island in the middle of the fjord. It turns out that it is a Boliden zinc smelter.

“You might have thought that they could have sited it somewhere it can’t be seen”, sniffs the First Mate. “Such beautiful scenery, and to be spoilt by this eyesore.”

“I suppose they needed to have somewhere near the water so that things could be shipped in and out”, I say. “And for the hydro-electric power to drive the plant.”

The bus arrives in the town centre and we clamber out.

“It’s lunch time”, I say. “There’s a small café over there. What about that?”

—–

The elderly gentleman picks up his pen, dips it in the inkwell, and begins to write.

“My dear Meg”, he starts. “Here at Odda since yesterday afternoon …”

Poor Meg. His eldest daughter. The others had all flown the nest, but not her. It had always been a puzzle to him as to why she had never found a husband. Educated, attractive, one would have thought the young men would have been queuing up. He had even used his influence to obtain a place for her as a governess with a wealthy family in the south of Scotland. But she had remained resolutely single. No grandchildren from her. However, every cloud has a silver lining, he thinks – he enjoyed having her around the Manse, helping with parish matters. She was good at it. And it meant that he could have this break and get away to see another part of the world.

He had enjoyed the cruise so far. The sail down the Firth of Forth from Edinburgh had been calm and pleasant. Despite this, he had felt queasy when they had reached the open sea, and had retired early. The next day hadn’t been much better, so he had dosed himself up with whisky and water and had another early night. On the third day, he had almost recovered and had stood on deck admiring the entrance to the Hardangerfjord before breakfast. Since then, he had been feeling as good as ever. So much so, that when they had arrived in Odda at the top of the fjord that afternoon, he had taken a ride in a stolkjarre up to Lake Sandvinvatnet and had seen two waterfalls, the Vidfoss and the Hildalfoss, and, across the lake, the mighty Folgefonna Glacier.

—–

“Come on”, I say, picking up the bill and going to pay. “Let’s get moving. There’s a nice walk along the river that will take us up to the lake.”

“Ready when you are”, says the First Mate. “By the way, what is a stolkjarre?”

“It’s a small two-wheeled horse-drawn buggy just enough for two people with a driver sitting up behind”, I answer. “They were common in Norway before cars arrived.”

As we head towards the river, we notice an outdoor exhibition of Knut Knudsen, a renowned Norwegian photographer born in Odda. He had made his name in the last half of the 19th century taking photographs of local landscapes, his work making a major contribution to the growing sense of a Norwegian national consciousness.

“Look, there’s one of a steamship anchored in the bay just where we came in”, shouts the First Mate. “That could have been the one that your great-great-grandfather was on.”

It had become fashionable in Britain in the late 19th century for those that could afford it to take advantage of the growing number of steamship companies to tour the fjords of Norway. My great-great-grandfather had taken one in 1889, and luckily had written letters back to his eldest daughter Meg describing his trip. Even more luckily, these letters had found their way down the generations to us. We had decided over the winter to follow as much of his trip as possible during our own voyage.

We follow the river crashing and tumbling over the rocks, and eventually reach Lake Sandvinvatnet. We stand in wonder looking at the same scene that my great-great-grandfather had seen 136 years previously. To the left are the two waterfalls he mentions. But no glacier!

“You need to walk around the western shore of the lake”, the woman in the Visitor Information had told us. “To a small hamlet called Jordal. The glacier doesn’t come down as far as it used to, but you can see it from there.”

Sure enough, at the head of the valley, we see the mighty river of ice topping the rock like icing on a cake.

“It’s hard to believe that when my great-great-grandfather was here in 1889, that he would have seen much more of it than we are seeing it now”, I say, as we walk back to Odda. “Proof of climate change, if ever one was needed.”

In the morning, we visit the museum in Rosendal. First up there is a film on how the Hardangerfjord was formed.

“Its geological history starts about 400 million years ago”, we learn. “Then, the three continental land masses of Laurentia, Baltica and Avalonia all collided with each other, resulting in the pushing up of mountains from the southern part of the United States right across to Scotland and Norway, with younger rocks being forced underneath the older rocks. In Norway, this created a huge fault along what is now the Hardanger fjord, with the oldest rocks generally on the south-east side and the younger rocks on the north-west side.”

“It’s pretty amazing, isn’t it?”, whispers the First Mate in my ear. “I am glad I wasn’t around when all these collisions were going on. Think of the insurance!”

“Over time, water eroded this fault line, weakening it”, the film continues. “When the Ice Ages came, glaciers formed in this huge fissure, grinding it and scouring it as they moved slowly down towards the sea. Eventually the ice started to melt, with meltwater running under the ice and further gouging out the fissure, resulting in fjords that were around 1000 m deep. Sediments from the erosion filled in some of this, so that the Hardangerfjord is now around 800 m deep for much of its length.”

It’s fascinating stuff. It’s difficult to imagine the power of the processes that can move massive amounts of rock around like sand in a sandpit, sculpting new landscapes as they go. Albeit very, very slowly.

“I am glad you enjoyed it”, says the friendly lady at the Visitor Information Office. “Now, the other place you should visit while you are here is the Rosendal Baroneit, a 17th century manor house. It’s just a short walk from here. You can’t miss it.”

We walk up the road to the east of the village, and eventually find a tree-lined avenue.

“We do guided tours in both Norwegian and English”, says the young man at the ticket booth at the gate. “But unfortunately there is only one tour left today, and it is in Norwegian. But perhaps if you ask the guide nicely, and if the other people agree, he might do it in English.”

We’re in luck. No-one objects.

“We actually prefer English”, says one woman as an aside to the First Mate. “My parents are visiting us from Kazakhstan and they speak more English than Norwegian.”

“Back in the 1600s, there was once a Danish nobleman by the name of Ludwig Rosenkrantz who married the richest heiress in Norway, Karen Mowat”, the guide tells us. “The couple were given the farm as a wedding present from her father, who had more than 500 farms in western Norway. They decided that they liked it so they built the manor house. It was finished in 1665. Shortly after Rosenkrantz was awarded a baronetcy by the King of Denmark, Christian V, the only one of its kind in Norway.”

He takes us through to the library. Ancient tomes line the walls.

“I wonder if anyone has read them all?”, whispers the First Mate. “Or do you think they are just there to impress people?”

“Titles were abolished in Norway in 1821”, the guide continues. “Title holders were allowed to keep and pass on their assets, and keep using their titles for their own lifetimes. But the title ceased when they died and no new ones were allowed to be created. The house remained in private ownership until the 1920s, when it was donated to the University of Oslo. Now it is preserved as a museum of an important part of Norway’s cultural history.”

We are taken through each room in turn – bedrooms, dining rooms, drawing rooms, ballrooms, ladies rooms, and the more mundane kitchens.

“Well, you certainly get an idea of how the other half lived”, says the First Mate. “It has a certain appeal. You know, one of my wishes when I was younger was to have a house with a turret.”

“Perhaps we can have one built”, I say. “Then I could lock you in it like Rapunzel.”

“Well, that is the end of the tour”, says the guide. “I hope that you enjoyed it. While you are here, I suggest that you see the gardens. They are supposed to be the finest Victorian gardens in Norway. The roses are especially beautiful.”

“You’ll never guess who I have just had a message from”, says the First Mate checking her phone as we walk home. “Simon and Louise. They have just arrived. They saw on their AIS that we were here, and thought that they would pop in too. I’ll invite them in for a café und kuchen.”

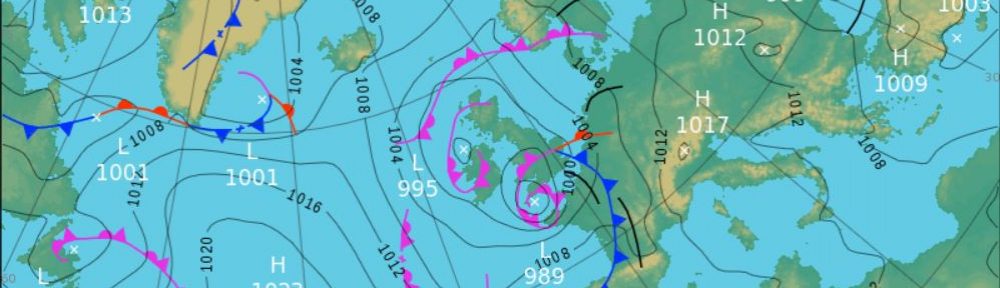

“There are strong winds and rain forecast for tomorrow”, explains Simon. “This looks like a good place to sit them out.”

The café und kuchen leads to dinner, where the conversation turns to the state of the world.

“You know, I can’t understand why we haven’t evolved beyond wars and strife by now”, says Simon. We all know that they are evil and unnecessary, yet we still seem to have them. Why?”

“Ah, you must subscribe to the Enlightenment idea of continual human progress”, I say. “Human affairs are always supposed to keep improving. The Stephen Pinker idea. I used to too, but after reading too much of John Gray and looking at what’s going on in the world, I am having second thoughts.”

“But you would think that any political system that was predisposed to wage war would ruin its economy so much that it couldn’t survive and would get weeded out”, he replies. “Just like unsuccessful reproductive strategies in biology.”

“It’s an interesting point”, I say. “But I am not sure that human affairs work like that. Look at the Roman Empire and most other empires in history. They were able to keep expanding because the countries that they conquered and bought under their control provided food and men for them to keep expanding. That was able to keep going for quite a long time, but eventually the costs of administering such a large empire outweighed the benefits and it collapsed. A bit the same with the British Empire.”

“But why haven’t we learnt from history that that is what happens in the end, and just not bother”, says the First Mate. “WW2 showed us that war and empire building was pointless, and that if we had a system of rules that applied to all countries big or small, then we would all benefit. So for the last 70 years or so, we have had peace in Europe and everyone has prospered.”

“Unfortunately, our current leaders seem to have lost sight of that”, says Louise. “There seems to be a move back to the authoritarianism that we saw in the 1930s.”

“It’s an interesting question”, says Spencer later over a nightcap. “Whether you humans should evolve towards greater cooperation rather than warfare, I mean. I think that It is all about raw power and prestige, and not really about devising better systems. Your leaders always want to leave a legacy that gives them prestige in the history books. If they believe they have the power to achieve that, then they will try and do it. Putin has visions of being a second Peter the Great in reunifying the old Soviet Empire, but it looks like he might have overestimated his power to do it. Trump seems to want an American Empire of the USA, Canada, Mexico and Greenland. It remains to be seen if either has the real power to achieve either of those aims.”

“The Law of the Jungle”, I say with a sigh. “Survival of the Strongest.”

Which side of the family was your great great grandfather and how is Meg connected?

LikeLike