“It’s right behind us”, I call out to the First Mate. “It looks like we are going to get wet.”

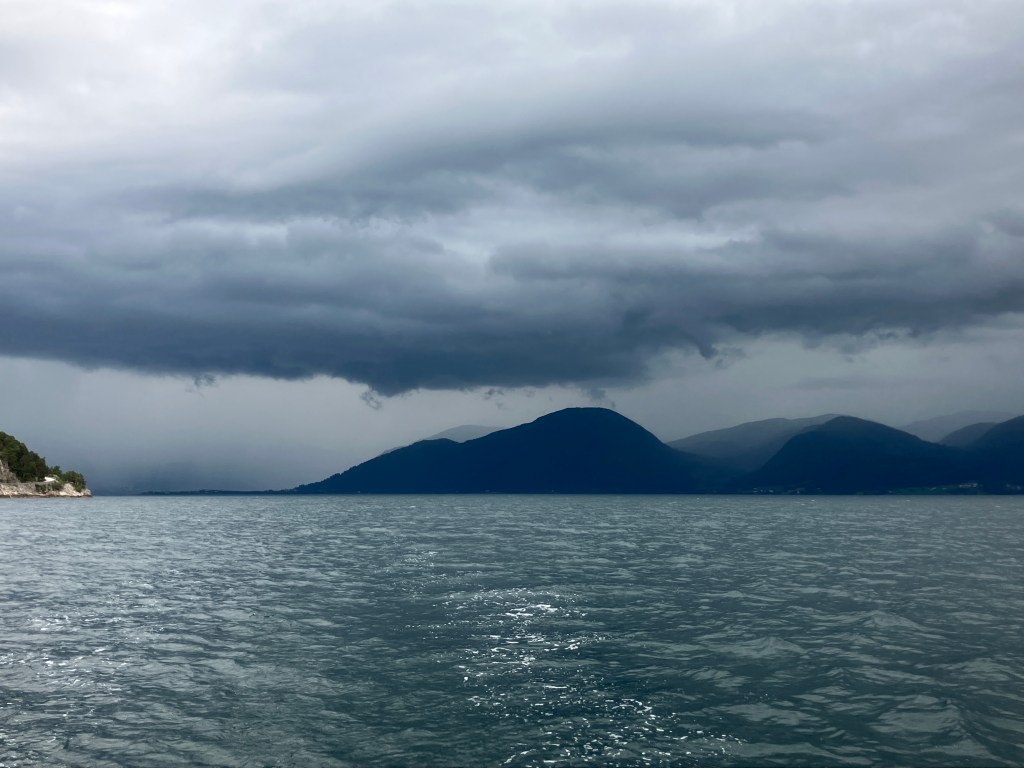

We are coming into the small harbour of Leirvik on the northern shore of the vast Sognefjord. A storm is chasing us from the south, and we are trying to get to shelter and tied up before it reaches us. About 200 m behind us we can see the ruffling of the water’s surface as the wind reaches it, our world reduced to a writhing mass of greys and blues. Raindrops begin to fall around us, spattering on the cockpit cover and the cabin roof.

For the last hour or so, we had seen the heavy dark clouds gather over the mountains to the south, and watched them with trepidation as they moved slowly across the fjord, wondering when it would be our turn to be engulfed. This looks like it might be it. But somehow it misses us. At the last moment it veers off towards the east, leaving only the perturbed water and the few raindrops in its wake.

“We’re not off the hook yet”, the First Mate shouts back, looking at the radar map on her phone. “There’s another one coming in. I’d say we have about ten minutes to get there.”

I push the throttle lever forward. We enter the small inlet, avoiding the salmon farms to starboard, and motor through the narrow marked channel leading to the harbour. Out of the corner of my eye, I can see the clouds appearing over the surrounding hills. Luckily there is a free space. We loop the lines around the cleats on the pontoon, quickly connect the power cable, pull down the sides of the cockpit tent, and retreat inside as the heavens open and the torrential rain starts.

“Phew, that was close”, I say. “I am glad that we didn’t get drenched. There’s something very nice about being warm and dry inside, listening to it pelting down outside.”

The rain stops in the early morning. We have a leisurely breakfast, top up with fuel, and set off northwards through Tollesundet. The wind is fitful, sometimes filling the sails and giving us a pleasant sail, other times dying to nothing so that once again we have to run the engine.

“This topography plays havoc with the wind”, I grumble, as we take a line between the islands of Skorpa and Sula. “It always seems to be against you, whatever way you are going.”

“Just be thankful for the magnificent scenery”, says the First Mate. “And that we have the weather to be able to see it.”

In the late afternoon we reach the delightful little anchorage of Hatløy.

“Let’s stay here for the night”, says the First Mate. “It’s such a fantastic view. And there is no-one else – we have it all to ourselves.”

“Sounds a good idea”, I say. “It’s designated as a nature reserve and landing is prohibited from April to July for the nesting season, but we can stay on board.”

We drop anchor and chill out. A heron screeches from the reeds at the water’s edge, two ducks paddle by, looking expectantly for titbits. A cormorant flies overhead. There is a splash as a fish jumps and disappears again. It’s idyllic.

We carry on northwards the following day. The landscape widens, with more sea room and less feeling of being hemmed in by steep fjord sides. Nevertheless, it is still impressive. We pass the imposing bulk of Alden island with its Norskehesten mountain.

“Norskehesten apparently means ‘Norwegian horse’”, says the First Mate. “But I can’t really see a horse in it. Perhaps from another angle. But it certainly is impressive. And look at the way the rock is twisted in this one we are just passing now. It looks a bit like a Swiss roll.”

We eventually reach the bustling harbour of Florø. On the way in, we pass the iconic Stabben lighthouse.

“We don’t need to stay too long in Florø”, says the First Mate. “I just have the washing to do and we can stock up on provisions. Then we should press on to Maløy while this good weather lasts.”

The next day we enter the Frøysjøen fjord. As usual, there isn’t much wind, and what there is is against us, so we have to motor until we turn eastwards where we are able to catch it on just enough angle to unfurl the sails. Even though we are only able to make three knots, we find it relaxing to sit back and enjoy the scenery without the noise of the engine.

“There looks to be a nice little anchorage coming up”, I say. “Hennøysund. Tucked in behind an island. We can stay there the night.”

“Sounds good to me”, says the First Mate.

It is good. Surrounded by high mountains on each side, it feels as though it is just us and nature. That’s if we ignore the occasional muffled throb in the main fjord on the other side of the island of ship engines carrying cargo or passengers from Florø to Maløy.

“Even in Norway with its small population, you never feel far from ‘civilisation’”, I muse.

In the morning, just around the corner from our anchorage, we find we are dwarfed by a massive cliff rising straight out of the sea.

“It’s the Hornelen Sea Cliff”, says Mr Fairlie in awe. “Nearly 3000 feet high. The highest sea cliff in Europe, by all accounts. Devonian sandstone. At one stage it was a sedimentary river basin. Then when the Baltica plate collided with North America, it was forced upwards.”

“Ah, you and your natural processes trying to explain everything”, says the minister. “I’d forgotten that you had a passing interest in geology. You’ve been reading too much of James Hutton’s ramblings.”

“Well, I have to admit I am a strong admirer of the work of our countryman”, rejoins his companion. “Through observation of the country around him, he came to the conclusion that the components of the land were once formed by the tides and currents under the sea into a consolidated mass, and then raised up out of the deep by unimaginable forces. And if that is true in Scotland, then it must also be true in Norway.”

“But where is God’s hand in all this?”, chides the minister. “Isn’t he the Creator of all things?”

“Far be it from me to disagree with such a learned man as yourself”, answers Mr Fairlie. “But as with any craftsman, He makes use of the natural laws to produce what He wants. It is the calling of geologists such as Mr Hutton to determine what those laws are.”

“Well, whatever its cause, it makes one feel humble just to contemplate it”, says the minister, looking again at the cliff. “We don’t have anything so spectacular in Scotland. I suppose people must have climbed to the top?”

“Apparently, you can walk to the top”, says the First Mate. “There’s a marked path you can follow. There’s a little harbour around the corner you can start from. It takes about four hours to get to the summit.”

“Shall we tie up and have a go?”, I say, tongue in cheek.

“Ten years ago I would have said yes”, she replies. “But now my knees aren’t up to it.”

Mine are the same.

“If the steamship were to stop, I would do it”, says Mr Fairlie. “But I don’t think that there is any chance of that. We need to get to Maløy by tonight. But it was worth seeing. Perhaps I might come back sometime.”

“Rather you than me”, says the minister. “I’m too old for that sort of thing now.”

We eventually arrive in Maløy and find a place in the small marina. There is a huge cruise ship tied up across from us.

“I suppose that is the modern equivalent of the cruise steamship that your great-great-grandfather was on”, says the First Mate. “But I have read that Norway is bringing in tough regulations in 2026 that will require cruise ships and tourist boats to be zero emissions, particularly in the UNESCO World Heritage fjords like Nærøyfjord and Geirangerfjord. I wouldn’t imagine that they would have worried about that in 1889 with their coal-fired ships belching smoke and other nasty gases.”

“That’s true”, I say. “And I read somewhere that they will even be using sniffer drones to check up on emissions from cruise ships in the fjords. But I wonder how it will affect sailing boats like ours? It’s not easy to use the sails only in the fjords, what with the fallvind and the like.”

“I guess we will have to replace diesel engines with electric ones eventually”, she says. “Some sailing boats are already doing that.”

“And a lot of the ferries that we see around us are already electric”, I say. “Or at least hybrid. They are taking it all very seriously. Good on them.”

The next day we sail for the island of Silda, to the north of Maløy.

“It’s hard to believe that this was the site of a battle between the British and the Norwegians in 1810 during the Napoleonic Wars”, I say, remembering something I had read in the travel guide. “Two British frigates engaged with some Norwegian gunboats based at the pilot station on Silda. The British captured two of the Norwegian boats, while a third was scuttled by its crew.”

“Hey, keep your eyes on where we are going!”, shouts the First Mate as we enter the tiny harbour. “You almost hit that boat!”

Strategically placed at the end of the breakwater is a shapely young woman who seems to have mislaid her clothes. She seems blissfully unaware of the effect of her presence on the psychology of sailors who have been too long at sea. Not that that applies to me, of course.

“I was just concerned that she might be feeling the cold”, I shout back.

Discussion over dinner that evening centres on the challenge tomorrow.

“I have to say that I am not really looking forward to rounding the Statt”, says the First Mate. “I’ve heard so many horror stories about it, it’s making me scared.”

The Statt is a peninsula that juts out into the Atlantic ‘like an angrily clenched fist’, as the Cruising Guide puts it. It is notorious for being dangerous in certain conditions, so much so that an escort service is provided for small boats wanting to round it. In fact, work has started on drilling a tunnel through the base of the peninsula large enough so that ships can sail through it and don’t have to go around it. With the Norwegian penchant for tunnel-building, I am surprised that it hasn’t already been built. Cost, I assume.

“We’ll be OK”, I say, not feeling as confident as I try to sound. “It’s just a question of picking your weather window. And with all this calm weather we have been having, there’s been nothing that could have made it rough.”

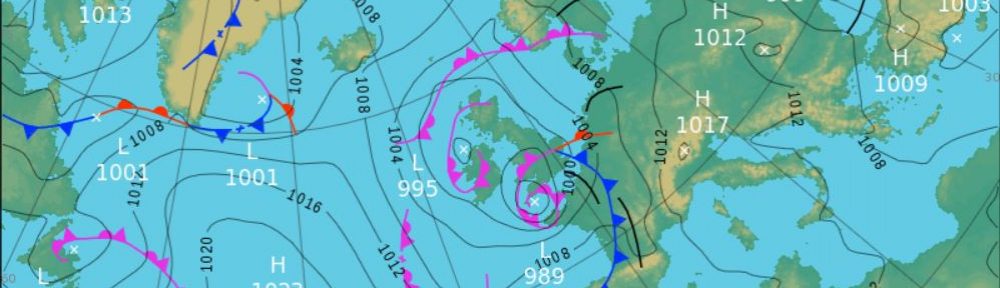

We study every weather app we can lay our hands on. One particular one gives the wave heights and wind speeds at the headland at three-hourly intervals. I painstakingly work these out for the week ahead trying to find a slot that has small waves and a southerly wind to blow us north around it as well as following the north-flowing current. Nothing is ideal, but there is a window that is relatively calm, albeit with a wind from the north.

“At least the wind is very low, so I think it should be OK”, I say. “We’ll just have to motor around it. Otherwise, we will have to wait a whole week before the wind changes to the south, and who know what the waves will be doing by then?”

“I hope you are right”, the First Mate says, not very enthusiastically. “How high does it say the waves will be?”

“It’s predicting a maximum wave height of 1.3 m”, I say. “That’s from the top of the wave to the bottom of the trough. And a 0.7 m significant wave height, which is the average of the top third of all waves. That’s not too bad. It’s a bit like the wash from a speed boat passing us. A bit bouncy, but tolerable.”

We set off in the morning. The sky is overcast, but at least there is not much wind. The sea is calm, but as we approach, the waves grow slowly in height, and Ruby Tuesday starts to plunge into each successive wave. The clouds thicken and seem to grow darker. A gust of wind rocks us from side to side. Or is it my imagination?

Eventually we reach Kjerringa, the peak at the outermost corner of the promontory. This is where two currents meet and the water is confused, with waves from one stream interacting with waves from the other. Ruby Tuesday pitches and rolls, not sure what is happening. Luckily it doesn’t last long, and we are soon back in more straightforward water.

“We’re over halfway now”, I say.

Slowly but surely the waves subside. Before long we are turning the corner eastwards again, and the water suddenly becomes smooth and the sun comes out.

“It really does generate its own microclimate out there”, says the First Mate. “I read that somewhere, but I didn’t really appreciate it.”

“Well, at least we made it”, I say. “We can relax now.”

“For the time being”, says the First Mate. “We still have two more designated ‘dangerous sea areas’ to go. Godø and the Hustadvika.”