“I’m going back to Tartu for my little sister’s graduation”, says the young man with a topknot sitting in the opposite seat to us. “Being the good brother, that sort of thing. I know Tartu well – I also studied there. By the way, my name is Sander.”

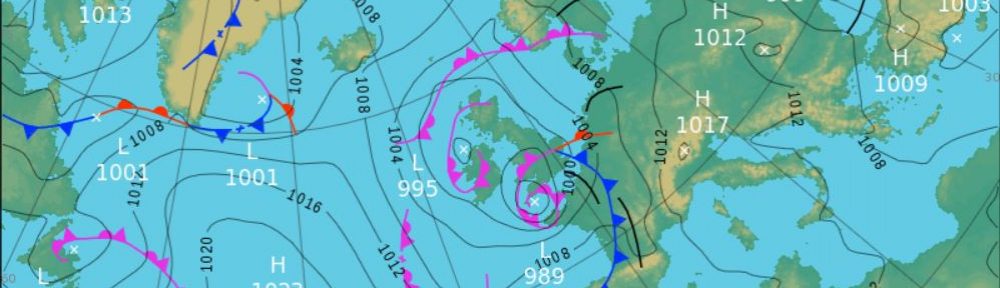

We are in the train from Tallinn heading to Tartu, Estonia’s second largest city, in the middle of the country. The weather forecast was for strong winds to persist in Tallinn, so we had decided that it would be a good opportunity to explore other parts of Estonia while we wait for them to subside. We had booked the tickets online – all tickets are booked online in Estonia as there are no ticket offices at stations any more – ridden the bikes to the station, packed them up, and stored them in the bike section the last carriage. It normally costs €5 to take a bike on the train, but folding bikes are free if they are folded and packed.

“Wow, that’s cool”, says Sander in response to his question of what we are doing in Estonia. “Sailing around Europe. That’s something that I have always wanted to do. My goal is to make lots of money, retire early, and do something exactly like that. You have really inspired me.”

The train enters the central forested area.

“What do you do?”, I ask.

“I actually work in London”, he tells us. “I am involved in writing software for specialised financial services for a large international company. The pay is great, and I invest most of what I earn. If it all goes according to plan, I am on target to retire in 15 years’ time when I am 40. The only thing is that I don’t have partner at the moment, so that is one of my priorities.”

“There must be lots of women who wouldn’t mind an exciting lifestyle without having to work”, says the First Mate.

“I actually had a date last night”, says Sander. ”It was a bit strange – although we are both Estonian and speak Estonian, we conversed in English. She also works abroad. We’ll see how it works out.”

There is a kerfuffle in the seats across the aisle from us. A loud bark and a plaintive meow. A woman with a cat in a cage has tried to sit down next to a girl with a nondescript-looking dog lying on the floor. The cat hisses in fright.

“I’ll find somewhere else to sit”, the catwoman says, moving further down the carriage.

“I think that you will like Tartu”, continues Sander, his topknot bobbing. “It’s a very beautiful city. It has the University, of course, and a lot of it was rebuilt in the old style after the city centre was destroyed by the Nazis and the Soviets in WW2. In fact, the Germans have had quite a bit to do with the city. The Livonian Brothers of the Sword came here in the mid-1200s and conquered it. They were on a crusade to convert the pagans up here to Christianity. Anyone who didn’t convert was put to the sword. The Brothers of the Sword were the ones who built the castle and cathedral on top of the hill. They also named it Dorpat which was used up to the time of independence when it was renamed to the old Estonian name of Tartu.”

Across the aisle, a little girl starts playing rock-paper-scissors with her father. Her face lights up each time she wins a round. The father tries to read something on his phone, but it is a lost cause.

“Shortly after the Brothers of the Sword took the city, it joined the Hanseatic League and became very prosperous through trade”, Sander continues. “Then over the next few hundred years it was fought over by Russia, Sweden and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The University was founded in the 1600s when the Swedish were in charge. Perhaps because of that it has always been central to the Estonian national revival – it is where the peace treaty between Estonia and Russia was signed after we became independent in 1918, and it was also where resistance to the Soviet Union and the Singing Festivals started in the 1980s and 1990s. This year it is the European Capital of Culture.”

The forest gives way to rolling farmland as we approach Tartu.

We wish Sander all the best with his future plans and romances, find our AirBnB to leave our overnight things at, and cycle into the city centre.

On the way we pass the Sacrificial Stone on Toompa Hill. Its surface is pockmarked with depressions in which pre-Christian people apparently left their offerings to their god Tharaphita. The guide book tells us that it is still used by university students who ceremoniously burn their lecture notes on it after they graduate.

“I think that is a story for the tourists”, says one person we ask about it. “I graduated from Tartu University, but no-one I knew ever did that. Anyway, its graduation day today, and there are not many ashes on the stone.”

We reach the city centre. The streets around the university are flooded with newly graduated students in their finery. Proud parents look on, meet their offspring’s boyfriend or girlfriend, and take endless photos.

We leave the celebrations and explore the town.

Appropriately, there is a sculpture of two kissing students in the Market Square.

“The story goes that they were student lovers who wanted to stay together forever”, says the First Mate. “Then one rainy day, they were struck by lightening when they were kissing, and were fused together in their embrace. They got their wish. But why they weren’t incinerated instead of being turned to metal, I don’t understand.”

“Don’t overthink it”, I say.

A little bit further on is the ‘Father and Son’ sculpture by Ülo Õun, with the two figures of the sculptor and his 18-month-old son the same height. It’s a little bit weird, but is supposed to represent the connection between generations.

Next up is the sculpture of Oscar Wilde and Edvard Vilde, the Estonian writer, sitting on the same bench. They share a surname, but were not related and never met.

“It’s just a joke”, says a woman who stops to take the photo of the two of us sitting between them. “Everyone likes Oscar Wilde in Estonia because he reminds them of our own Edvard Vilde.”

Eventually we reach the Emajðgi river running through the city.

“Apparently it just means ‘Mother River’ in Estonian”, says the First Mate.

The next morning, we cycle up to the Estonian National Museum on the outskirts of the city.

“It’s enormous”, says the First Mate. “I wonder why they made it so big?”

“It seems that it used to be a Soviet airbase where they kept their strategic nuclear bombers”, I say. “I suppose they needed a bit of space for that.”

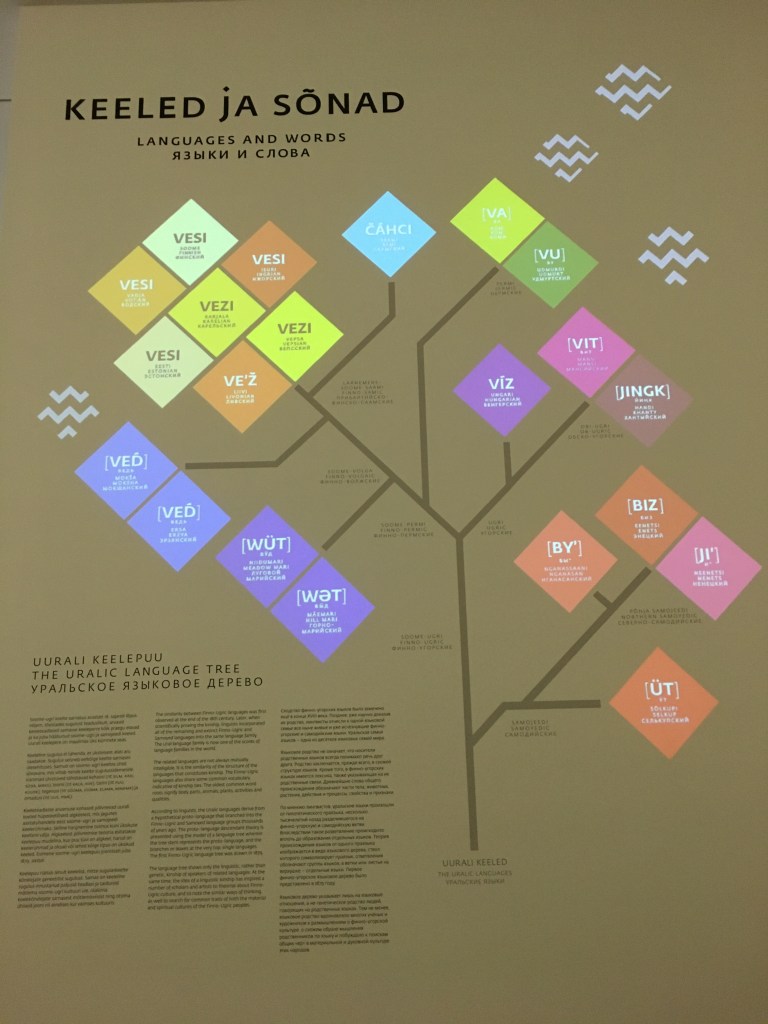

We start with the Echo of the Urals exhibition, which explores the Uralic family of languages that both Estonian and Finnish belong to. It is thought to have originated in the foothills of the Ural Mountains and from there spread westwards as far as Norway and as far eastwards to eastern Siberia. The Finno-Ugric languages are a sub-group within this broad family.

We learn how researchers have pieced together evidence that these languages are related, not only through words, but also through the many overlaps in the pre-Christian religious concepts and folk poetry relating to farming, hunting, fishing. For example, many maintain contact with ancestors through prayers and laments, sing long dreamlike songs, and offer sacrifices to gods and spirits to help them survive in the harsh environment. They believe that a person has several souls, although only one is reborn.

Interestingly, language and culture are not always linked to the genetics. For example, Latvians and Lithuanians have a similar genetic heritage to other Finno-Ugric peoples, but their languages are Indo-European in origin, while Hungarians have a European heritage, but their language is Finno-Ugric.

“Fascinating”, says the First Mate. “I never realised before that there are so many different languages in this part of the world. And so many different national costumes too.”

“It was interesting to see the very first Estonian flag”, I say over a coffee in the restaurant later. “Apparently is was designed by a theology student here in Tartu back in 1881 when Estonia was still part of the Russian Empire but nationalist feelings were emerging. Blue represents the country’s bright future, black represents its dark history, and white the gaining of enlightenment and learning. It had to be kept hidden in Russian times, but was brought out at the times of independence in 1917 and 1989. Now you see it everywhere.”

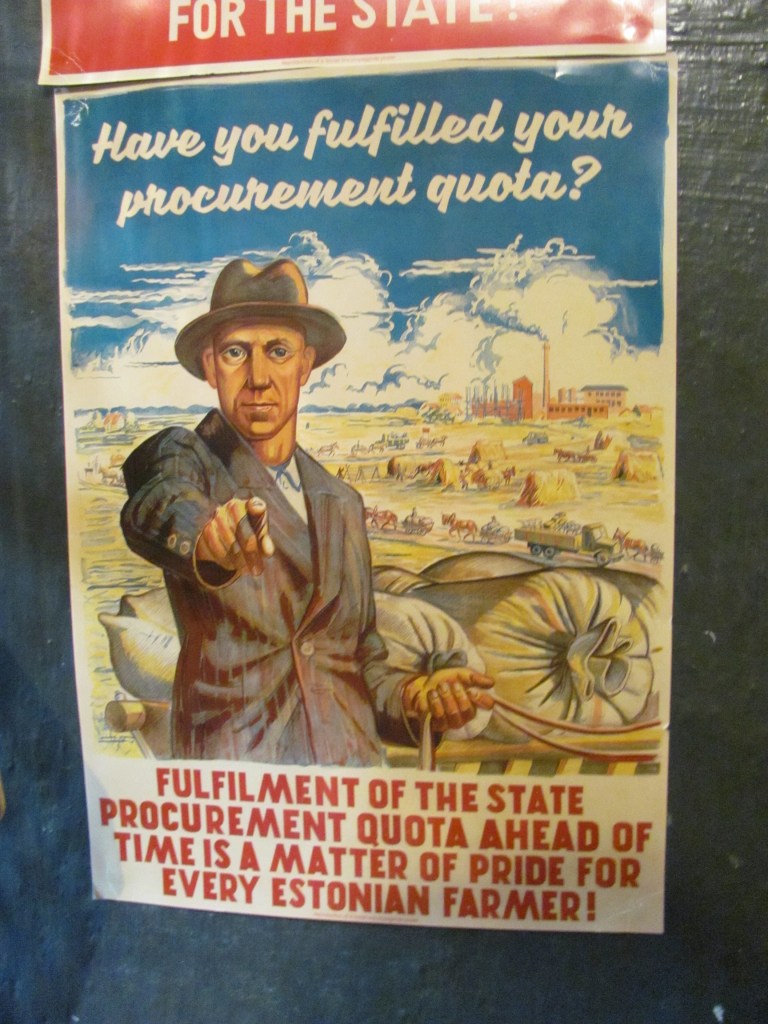

“Did you see the joke about life in Soviet times?”, asks the First Mate. “Everybody goes to work, but no-one does any work. Nobody does any work, but the plans are fulfilled. The plans are fulfilled, but the shops are empty. The shops are empty, but the homes have everything. Homes have everything, but nobody is happy. Nobody is happy, but everybody votes in favour of the government.”

“It is amazing how rapidly they have embraced modern technology since those days”, I say “It’s only been about 30 years, but within that short time they have created a modern digital economy. Most interactions with government are done online now. And did you see the little cube satellite that was built at Tartu University and sent into space with a European Space Agency rocket to test a solar sail? The camera they developed for it was so good that it was later used in earth orbiting observation systems.”

We cycle back into the city centre. Preparations are underway for the Midsummer Festival procession. It starts at four o’clock, but unfortunately we can’t stay to watch it, as we have our train back to Tallinn to catch.

“At least we can get a few photos of the various costumes”, I say. “We can pretend we saw the procession.”

We arrive back in Tallinn in the early evening. Later, we cycle over to Stroomi beach on the opposite side of the peninsula from where we are moored. There is supposed to be a midsummer celebration there with a fire. Sure enough, we find a band playing, a fire burning, and people dancing¸ drinking, eating, and wading in the shallow waters of the bay.

We find a place on the beach and eat our snacks and drink our wine. The First Mate strikes up a conversation with a woman nearby. It turns out that she is Russian.

“Yes, I am Russian”, she says. “My parents came here to work when Estonia was a Soviet Republic. I was born here and have lived here all my life. Tallinn is my home. Most of the Russians live in the area at the back of the beach. It’s definitely the poorer end of town. ”

We had passed through it on our way.

“We are certainly discriminated against”, she continues. “We don’t have Estonian citizenship and we don’t get such good jobs. Our unemployment rate is higher than Estonians, especially amongst women.”

“But why don’t you automatically get Estonian citizenship if you were born here?”, asks the First Mate. “That would be fair.”

“Well, when Estonia became independent in 1991, they decided to make it a restoration of their independence before 1939 rather than create a new state”, the Russian woman says. “That meant that anyone that came into the country after 1939 and their descendants were not granted automatic citizenship but had to apply for it and meet the requirements, one of which was to speak Estonian. It was basically targeted at us, the ethnic Russians. The Estonians are paranoid about being outnumbered in their own country.”

“Do the ethnic Russians protest much about it?”, the First Mate asks.

“Not really”, the Russian woman says. “Most of them don’t want to stir things up as they have a much better standard of living than if they were in Russia, and also living in Estonia gives them the right to travel and work in the rest of the EU, which they wouldn’t be able to do if they lived in Russia. I am married to a Danish man, for example.”

It’s a tricky one. The ethnic Russians do seem to be discriminated against in some aspects, but equally I can understand the Estonian viewpoint – having a significant proportion of their population originally from a hostile neighbour is not conducive to sleeping easily at night. Especially looking at the pretext justifying the Ukrainian war.

There is a loud shout from the crowd. A fire engine has arrived. It is past sunset and is time to put the fire out. The firemen unroll their hoses and turn on the pump. As the jet of water hits the fire, there is a loud hiss and clouds of dense steam billow skyward. They spray water on the remaining logs from every angle to make sure there are no glowing embers left. Soon all that is left are one or two charred logs on the sand. The evil spirits have been chased away by the noise of the band and the dancing, and the harvest will be good. The love spells have been cast and will ensure that a new cohort of Estonians are born in the springtime.

Ruby Tuesday crew – thank you for another great post.

Best regards from Alba with crew. Currently morred at Femö Island south east Denmark. Another place with very interesting history.

http://www.femo.dk (only danish be there is google translate I guess)

The islands tagline is “Where the Sky kisses the Earth”

Fair winds,

Martin & MIa

LikeLike

Thanks Martin & Mia. Sounds good where you are. We did explore quite a bit of the Danish archipelago on the way up, but not Femø. Perhaps on the way back. Like the tagline.

LikeLike