“We could stop at Fejan”, says the First Mate, looking up from the harbour guide. “It’s not far from here, and it would be a good jumping off place for the Åland islands. It’s just up around the next headland.”

We have started our summer voyage at last. We had left Svinninge marina in the morning, and had wended our way through the islands of the Stockholm archipelago, managing to dodge all the ferries coming and going. The wind had been fitful – sometimes strong gusts, then dying to nothing. Nevertheless, it had been an opportunity to check that everything was working on Ruby Tuesday, and accustom ourselves to the art of sailing again.

“Fejan sounds fine to me”, I say.

The small harbour comes into view. We tie up alongside the outer pontoon. We are the only boat there. There appears to be no-one on the land either.

“It looks like there has been quite a storm here”, calls the First Mate. “This steel signpost is all buckled. And look at this bridge to our pontoon. It’s been ripped from its metal fixings on the main pier. I am a bit scared to even put my foot on it.”

We had heard while we were preparing the boat that there had been a violent storm in the Baltic back in November and that many of the small harbours and marinas had been substantially damaged. There was doubt in many cases as to whether they would be repaired in time for the 2024 season.

“The harbour guide says that Fejan used to be a quarantine station”, says the First Mate. “It was built way back in the early 1800s when cholera was spreading through Europe, so any new arrivals to Sweden had to stay here until they were cleared to enter the country. Needless to say, many of them died before they were cleared.”

At the end of WW2, a lot of Estonians fled their country as they feared retribution for being on the wrong side of the invading Russians, while others didn’t want to live under communist occupation. The ones that came to Sweden were kept on Fejan in quarantine.

We explore the small cluster of houses surrounding the harbour, dominated by an imposing-looking restaurant. Apparently it used to be the autopsy building and morgue for the quarantine station. There is a feeling of sadness, not helped by the solitude.

“Come mid-summer, it’ll be a hive of activity, though”, says the First Mate. “I wonder if they will realise that there were once dead bodies on the tables they are happily eating their fine food from?”

“The meat-eaters amongst them are eating dead bodies anyway”, I say wryly.

We set off the next morning sailing for Kökar, an island cluster in the south of the Åland islands. It is nearly 60 miles away, but the south-east winds are favourable. The sails fill on a pleasant beam reach, and soon we are comfortably speeding eastwards at 7-8 knots.

We near Kökar in the evening. Furling the mainsail, we turn to the north to round the headland into Sandvik harbour. On the hill above us, we see the white walls, red roof, and spire of Kökar church.

“Have you seen that ferry behind us?”, says the First Mate, just as we enter the narrow buoyed channel to the harbour. “I am not sure there is enough room in this channel for both of us.”

I had seen it. Luckily the channel widens a little just before the ferry dock, so I furl the genoa and tuck into there. The ferry passes with mere metres to spare.

We soon reach the small harbour for sailboats at the top of the bay and tie up. Once again, we are the only boat there. A beached ancient hulk greets us.

“Did you know that you are supposed to pronounce Köker ‘Shirker’?”, I ask. “The K often has a ‘sh’ sound in Swedish, and the ‘ö’ has a short ‘ir’ sound a bit like in German. And it has nothing to do with the inhabitants being work-shy.”

“Ho, ho”, groans the First Mate with a look of weary resignation. “I think your jokes are getting worse, if anything.”

The next morning we borrow some bikes from the café and cycle up to the church we saw on the way in. It is locked, but the key is kept by one of the islanders living nearby who is usually happy to open it to visitors. It turns out that he is the church organist.

“Originally, there was a Franciscan monastery here dating from the 13th century”, he tells us. “You can see the ruins of it within the small museum behind the church if you are interested. Then a wooden church was built in the 14th century. Of course, both were Catholic, dedicated to Anna, the grandmother of Jesus, but in 1544 AD it became Lutheran when King Gustav of Sweden split from the Catholic church and converted the whole country to Lutheranism. Åland and Finland were part of the Swedish Empire at that time. But this actual church we are standing in dates from 1784 when it was rebuilt, although the baptismal font over there is from the original church.”

”And this beautiful ship here”, asks the First Mate, pointing to a model of a ship suspended from the ceiling. “What does that signify?”

“Well, the story is that a local farmer was travelling somewhere by ship in the 1700s, but was captured by North African pirates”, the organist explains. “He was held by them for several years, but eventually managed to escape, and when he made it back to Kökar, as a mark of his gratitude to God for saving him, he decided to build a model of the pirate ship that captured him.”

“A poignant little story”, I think, although the thought crosses my mind as to why God would be interested in a model of a pirate ship.

We walk to the top of the hill overlooking the vastness of the Baltic Sea interspersed with islands of the archipelago. Behind us the wind whistles through the pines surrounding the church, conveying a sense of loneliness. And yet, to weary seafarers arriving from a long storm-tossed voyage it must have looked like a sanctuary offering protection from the elements. I read later that Kökar was one of the resting places on the ‘Danish Itinerary’, a 13th century sea route from Utlängan in south-east Sweden to Tallinn in present-day Estonia.

A sailboat appears from behind one of the islands from the north.

“I wonder if that is Simon and Louise?”, I say. “They are certainly coming from the right direction.”

Simon and Louise are a couple we met on the Cruising Association Rally in Åland last year. We had arranged to meet up again this year if we are near each other. We are, so they had suggested meeting up today.

We watch the boat until it passes below us.

“It’s definitely them”, says the First Mate. “I recognise the boat. Look, there is the Red Ensign on the stern.”

We wave, but they don’t see us.

We meet them as they arrive in the harbour and give them a hand tying up. Over coffee and cakes we catch up on everything each other has been up to since last year.

As the sun goes down and it suddenly grows cold, we decide to adjourn to the local hotel restaurant for something to eat.

“We had a bit of an ‘adventure’ here in Kökar last year”, says Simon over dinner. “One that we are not too keen to repeat.”

“We were just about to leave”, Louise continues. “We were reversing out, and suddenly there was a horrible graunching noise and the engine stopped. Something had caught itself on the propeller. Simon put on his wetsuit and went down to investigate – it turned out to be a submerged stern buoy that was being held down by its chain. You couldn’t see it. We had reversed right over it, and the chain had caught around the propeller.”

“Every sailor’s nightmare”, I say.

“Luckily, the harbour did eventually accept responsibility and agreed to pay for the damage”, says Simon. “But trying to get the money from them was the next part of the saga. We kept on emailing and phoning them, and they kept saying, it’s alright, we’ll pay for the damage. But the money never appeared.”

“In the end, we found their insurance company”, continues Simon. “They confirmed that the damage would be covered, and told the harbour to pay us. So in the end they did, but it was a lot of hassle. With all the delays, it ruined our sailing season.”

On the way out of the restaurant, we briefly chat with a German girl at the next table.

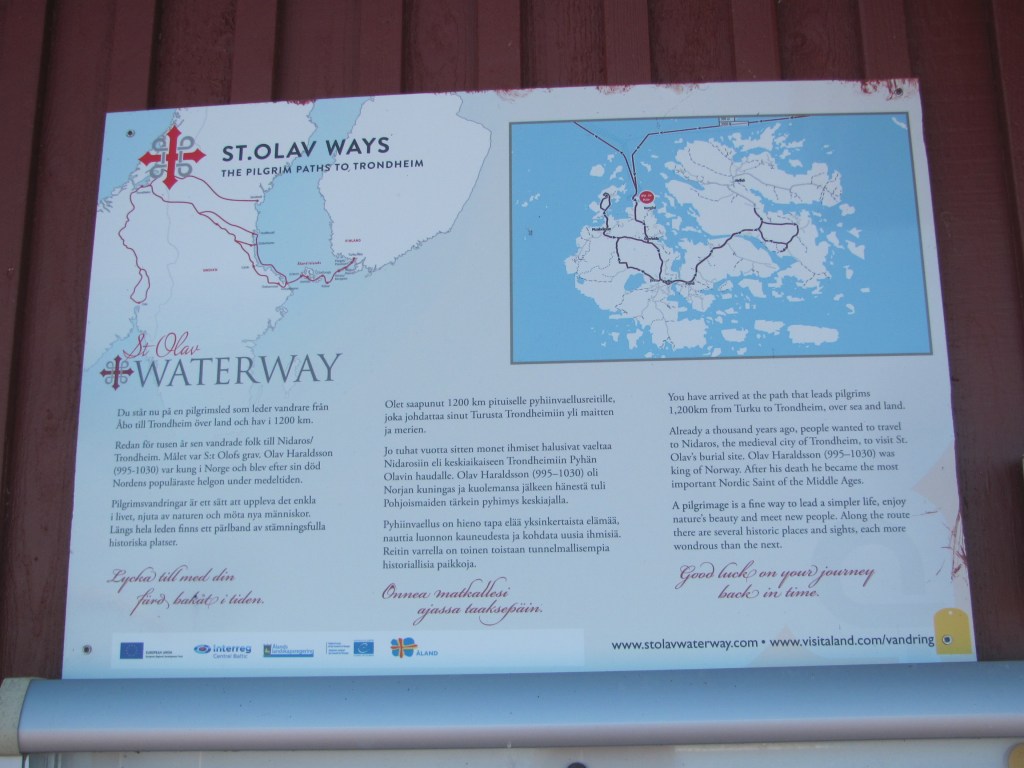

“I am on a project at the University of Trondheim in Norway”, she tells us. “Trondheim used to be a major Christian pilgrimage centre in medieval times. People would come from all over Europe to visit the shrine of St Olav who was buried in Nidaros Cathedral there in 1030 AD. We are trying to resurrect some of the major pilgrim trails leading to the city, both for those wanting the spiritual experience, but also for recreation. The one that I am working on at the moment is called St Olav’s Waterway, starting in Turku in Finland. It’s about 340 km long, and the only water-based route. You walk through the islands on the route and catch a ferry from one island to the next. Kökar is one of the islands on the route. When you get to Eckerö near Mariehamn you take a ferry across to Hudiksvall in Sweden. From there you can walk all the way through to Trondheim in Norway.”

“That’s quite a walk”, says Louise, no stranger to trekking herself. “Why are you doing it?”

“I am not religious myself”, the girl says. “But people go on pilgrim walks for all sorts of reasons – the sense of achievement, creating the time to resolve crises in your life, enjoying the camaraderie of others doing the same thing, pondering the big questions of life. Most people say it is a life-changing experience one way or another. For me it’s being in the great outdoors and the sense of achievement.”

“I wonder what was so special about St Olav?”, the First Mate asks me later.

I read that he lived from 995-1030 AD, was a king of Norway, and instrumental in bringing it together as a country. He was made a saint as he was credited with introducing Christianity to Norway. This was despite not actually having all that much to do with it, and what little he did do, did fairly violently in that people who refused to become Christians had their heads cut off.

“Interesting criteria for becoming a saint”, says the First Mate.

“Perhaps it’s the results that count in religion, not the means”, I say. “Anyway, it says that miracles starting happening near his remains after he died, so they thought this deserved a sainthood. People then started making pilgrimages to his grave hoping some of the miracles might rub off on them.”

“I am sure the church didn’t do too badly either from the influx of pilgrims all coming to spend their money on indulgences and the like”, says the First Mate. “The forerunner of modern tourism. Create an attraction, and just wait until the punters roll in.”

“Now, now”, I say.

“Let’s take the bikes and go out to the museum today”, suggests the First Mate over breakfast the next morning. “It’ll be a chance to see another island.”

It is about 8 km. We pass over a bridge to the next island and through some gentle rolling pastureland. Only two cars pass us on the way.

“It’s so peaceful here”, says the First Mate. “It’s so nice not to have the noise of cars everywhere you cycle.”

We arrive at the museum. It’s closed. But in one of the small adjoining buildings near the entrance, we see a girl in her 20s with a furry dog. A Finnish Lapphund, perhaps.

“Yes, I am afraid it is closed”, she tells us. “But two buildings – the traditional farmhouse and traditional fisherman’s cottage – are open all the time. You can go and have a look through those if you like.”

“Are you one of the staff?”, asks the First Mate.

“No”, says the girl. “Not museum staff, at least. I have just started a small business here making ceramics. But I have lived on the island for nearly seven years. I came originally from Helsinki.”

“You must find it very quiet here compared to the city”, says the First Mate. “Most of the people we have met here so far seem to be of retiring age. Don’t you miss your friends in Helsinki?”

“It’s true that most people on the island are older”, the girl says. “And yes, I do miss my friends a little bit. It’s not like I can just pop around and see them after work, and it’s quite an effort for them to come over here and visit me. But I had had enough of the city stressing me out, so I decided that what I needed was peace and quiet – ‘me-time’ – so I came to Kökar. I love it here. I find the landscape and the coastline very inspiring, and, yes, the people too. I try to incorporate my inspirations into my ceramics.”

“And you have your dog for company”, I say, stroking the fur behind the dog’s ears. “He or she is beautiful.”

“It’s a she”, she says. “But unfortunately she’s not mine. I am just looking after her for someone.”

“I think I would find it too lonely to be here all by myself”, says the First Mate as we look around the traditional fisherman’s cottage. “I need people around. And the number of potential partners on the island must be limited.”

“It takes all sorts”, I say trying to be profound. “But I can see where she is coming from. Maybe you need isolation to be creative. Away from the distractions of civilisation. Including potential partners.”

Good morning Brigitte and Robin, all the best for this years sailing season. Enjoying to read about your adventures again. Good winds and good luck, Gisela

LikeLike

Thanks Gisela. So far, so good. Hoping you can join us again at some stage.

LikeLike

Your post about Tallinn was awesome

LikeLike

Pingback: Fading batteries, a crowning cathedral, and a harnessed waterfall | Ruby Tuesday