“Strong winds are being forecast for the weekend”, says the First Mate. “I think we should get to Umeå and find somewhere safe where we can wait it out, and at least we will have something to do. Joanne and Peter can also catch the ferry across to Vaasa in Finland.”

“Good idea”, I agree. “I’ll plot a route.”

It takes two days to reach Umeå. We break our journey at the tiny harbour of Järnäsklubb, an old pilot station, before continuing on the next day. We eventually tie up at Patholmsviken sailing club marina in Holmsund, 15 km south of the Umeå. We can’t sail closer as there are permanent bridges in the way.

Peter and Joanne leave the next morning. It’s been good to see them. The time has flown since they arrived, but now they have to catch the ferry over to Vaasa in Finland, and from there the train down to Helsinki. A taxi has been booked for 0700 to take them from the club marina across to the ferry terminal on the other side of the harbour. We wait at the club house for it to arrive. At 0710 it still hasn’t turned up.

“There’s a barrier across the entrance to the marina”, one of the club members tells us. “Cars can’t come in unless they know the code. He’s probably waiting there. You’ll have to walk down.”

We rush with the suitcases and their other luggage to the entrance. It’s quite a long way. Precious minutes tick by. Luckily the driver is still waiting.

“Phew”, says Joanne, panting. “I was worried that he would think it a hoax call and leave. I didn’t fancy walking around to the ferry terminal with all this luggage.”

In the afternoon, the First Mate and I catch a bus into the city centre. We decide to have lunch in the MVG-Gallerian shopping centre. We both have the salmon.

“It says that Umeå has a population of 130,000 people”, says the First Mate, reading from the guide book. “Apparently the name comes from the Old Norse for ‘roaring river’. It was burnt to the ground by the Russians in their Pillage of 1719-21, and again in 1888, the same day that Sundsvall was burnt down. Rather than rebuild the city in stone as Sundsvall did, the Umeåns decided to construct wide avenues with birch trees along their sides to stop future fires from spreading. Nowadays, the city has two universities, and the CRISPR gene-editing technique was developed here. In 2014, it was named as the European Capital of Culture.”

“I wonder if they called the gene technique CRISPR because of all the fires?”, I ask.

“Was that supposed to be one of your jokes?”, says the First Mate.

“Not really”, I say with a sigh. “It was pretty marginal. Not everyone will get it.”

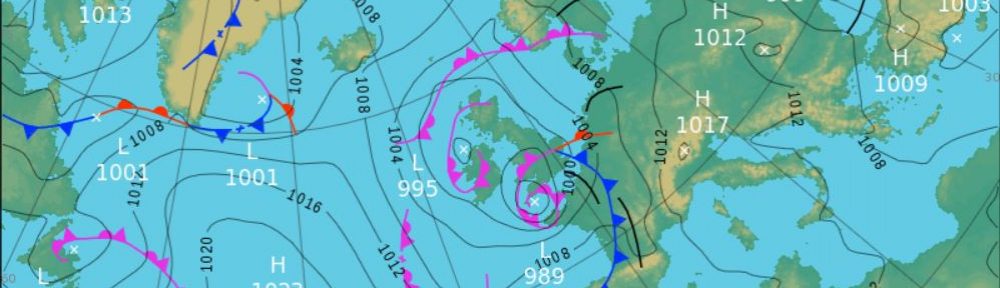

The strong winds and rains arrive that evening from the south. We batten all the hatches and put double lines on the moorings. It feels cosy inside the boat with the wind whistling in the rigging above and the rain pelting on the windows. The instruments show that the winds reach 45 knots.

In the morning, the rain has stopped, but the winds continue.

“Let’s take the bus into town again”, says the First Mate over breakfast. “You can go to the museum, and I can browse the shops.”

I get off at the Fridhem bus stop and walk the few hundred metres up to the Västerbottens museum. Its remit is to preserve the cultural history of Västerbotten County.

“It’s all free”, the young man at the reception tells me. “There are various exhibitions inside, and an open-air display of reconstructed aspects of life in Västerbotten County. They are even making traditional bread today. One of the exhibitions is on Sámi culture.”

I start at that one. An intelligent-looking stuffed moose greets me.

“I prefer to be called an elk”, she says. “We are in Europe after all. But you can call me a moose as well. I don’t mind. And while you are here, don’t forget to see the skis. They are the oldest in the world.”

Next up is a replica Sámi tent. The accompanying sign tells me that the Sámi were traditionally semi-nomadic reindeer pastoralists, but also made a living from coastal fishing, fur trapping, and sheep herding. Their homelands stretch across the northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Kola Peninsula of Russia. I crawl into the tent and try to imagine what life inside would have been like with a blizzard howling around me. But the lustrous perfumed reindeer skins on the floor somehow don’t quite convey the full experience.

In another room, there is an exhibition on the National Forest Inventory, the aim of which was to count and measure every tree in Sweden to get an idea of how much timber there was. Apparently the results showed there was more than they thought at the time, so the country breathed a great sigh of relief. And went out to cut some more.

In the open-air part, I come to the old bakehouse. A man and a woman in traditional dress are making bread.

“We are making tunnbröd”, says the woman. “Traditional northern Swedish bread. We are husband and wife, so it’s a team effort – he does all the mixing and kneading of the dough, and I do the baking.”

“It’s made from barley flour”, explains her husband, as he rolls out some dough into thin flat pancakes. “You can also add some rye flour or wheat flour if you like. Some people even add mashed potatoes. Then I add water, bicarbonate, yeast and salt.”

Much the same as what I do when I make bread at home.

The woman picks up the pancakes and places them on a long-handled board. She pushes the board into the oven with logs burning at the back and sides, and with a deft flick of her wrist, deposits the bread onto the hot tiles in front of the logs.

“We need to keep the tiles hot”, she tells me. “So when we have a break, we pull the burning logs forward over them to heat them up again.”

The aroma of baking bread fills the small room. My stomach starts to rumble.

“Here, this one is for you”, she says, folding one in half. “Try it.”

I break off a bit of the bread and taste it. It is warm and soft, and delicious in the way that only freshly-baked bread can be.

“This one has a few fennel seeds in it”, she says, noticing the look on my face as I try and recognise the flavour. “Here’s a pamphlet with the recipe. You can give it to your wife.”

“Ha, I am the bread maker in the family!”, I say with a smile.

As I walk back to the museum building, I see a group of people pointing and talking excitedly. Curiosity piqued, I join them to see what they are looking at. From our vantage point on the hill where the museum is located, we can see plumes of thick black smoke coming from somewhere in the city.

“There’s a fire in the city centre”, one my fellow observers tells me. “The police and fire brigade are there and they are trying to put it out.”

I try and call the First Mate, but she doesn’t pick up.

The next bus into town leaves in twenty minutes. Before long, I am at the central bus station.

“There’s been a fire here”, says the First Mate when we meet. “It’s the same building that we had lunch in yesterday. There’s been smoke everywhere. They have cordoned it all off. It’s a bit of a nuisance as I had hope to do some shopping for food for tonight, but you can’t get to it.”

We watch one of the fire engines lift firemen up to spray the building with water.

Later we hear that one of the fans in the ventilation system of the building had caught fire. Luckily everyone in the building had been evacuated and no one had been injured.

“I bet the salmon they are serving in the place where we had lunch yesterday will be CRISPR today”, I say on the bus back to the marina.

“Don’t push it too far”, says the First Mate. “It wasn’t very funny the first time.”

“Well, at least the birch trees seemed to have worked”, I say. “The fire didn’t spread to any of the other buildings.”

“It’s rather amazing that we should be in a city that is famous for having burnt to the ground in 1888 on the very day that there is another fire in the city centre”, says the First Mate.

In the evening, we cook dinner in the marina clubhouse. I get talking to a woman from Lithuania. The conversation predictably turns to the war in Ukraine.

“Most Lithuanians strongly support Ukraine”, she says. “We know what it is like to be under the control of the Russians, and it is not something we would willingly go back to. We are part of Europe now, and we want to stay that way. The Ukrainians are the same. I really hope that they win.”

“Are people in Lithuania worried about Russia invading?”, I ask. “To try and recreate the old Soviet Union, I mean?”

“Not really”, she says. “As individuals, there’s not a lot you can do. Most people just get on with their lives. There’s no point in worrying. And we are part of NATO. As are Finland and Sweden now. That should help protect us against any aggression.”

She is sailing with three other friends around the Baltic.

“I like travelling”, she says. “When I was younger, I was interested in learning about different religions to see what each had to offer. I lived in India and the Far East for a while. While I was in India, I stayed in an ashram.”

“I thought that most people in Lithuania were Christian?”, I say.

“They are”, she says. “But Christianity was never really accepted in Lithuania as a national religion. It is seen as a foreign one forced on us by the Catholic Church in Europe against our will. Lithuania was really only Christianised in the 1600s, one of the last countries to be so in Europe. Often the conversion process was pretty violent, in that if you didn’t accept Christianity, you were killed. A lot of people see it as a foreign religion from a hot, dry, far-off land that doesn’t have any connection to our culture.”

“I read somewhere that there has been a resurgence in Lithuania in the old pagan religion before Christianity came”, I say.

“Yes”, she says animatedly. “I am impressed you know about that, not being a Lithuanian. It’s called Romuva. It is closely linked to nature and the culture of Lithuania, and tries to bring together our old songs, dances and rituals that existed before Christianisation. The Communists tried to stamp it out, but there’s been a resurgence since the breakup of the Soviet Union. I often attend the rituals – sometimes in a grove or place that has been sacred since ancient times. We see the cosmos as a great mystery, and celebrate it and nature as we see ourselves as part of them. It’s somehow awe-inspiring and beautiful to think that we have risen from nature and will one day go back to it.”

“It seems very relevant to the modern day efforts to preserve the planet”, I say.

“Absolutely”, she says. “We have respect for the Earth and every living being on it, whether they be microbes, plants or animals – they are all symbols of life. Rivers are also important – they are seen as a boundary between life on one side and death on the other, and therefore must be kept clean.”

“I recently saw an old Michael Palin documentary about fire-walking in Estonia, I think it was”, I say. “It was one of the rituals of the Old Baltic religion.”

“Yes, we see fire as the representation of the Divine and the ultimate purifier”, she says. “Some people believe the flames carry their prayers and offerings to the gods.”

Later I discuss the conversation with Spencer.

“Yes, it’s interesting isn’t it?”, he says. “Apparently the old Baltic beliefs derive from the ancient religion of the Proto-Indo-European peoples from between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. It is polytheistic, meaning that there are many gods, often for specific things such as the sky, the Earth, the sun, forests, the sea, and so on. There are even links with Hinduism in India, which also evolved from the PIE religion, and much of the cosmology, and many of the beliefs and rituals between the Balts and Hindus are similar. Some of the gods’ names also sound the same. So much so, the Lithuanians have even invited Hindu sadhus to participate in their rituals. They take pride in their religion being so ancient in comparison to newcomers like Christianity.”

“Almost as though it was the true religion of Europe and Asia”, I muse. “I wonder if that was why she spent some time in an ashram in India?”

“Quite possibly”, he says. “But I am not sure why you humans think there has to be a ‘true’ religion. I am just a lowly spider, but to my mind all religions are just a way of helping you make sense of the world around you and to provide comfort in a hostile world. You create gods or a god who is supposed to have created the cosmos and you, who cares for you while you are alive, and whom you will eventually join again when you die. Is there any evidence whatsoever of these gods? None whatsoever! How then can you talk of a ‘true’ religion? Surely they are all just something you make up to provide an explanation for something you don’t understand, or myths that are not true but allow you to share the experiences of your ancestors in the past?”

“Come on”, calls the First Mate from the cabin. “You should get to bed. We have an early start tomorrow. And tell Spencer to go and catch some flies.”

I say goodnight to Spencer and go downstairs, making a mental note to explore these ideas in more detail when we sail to Lithuania next year.

Being back from the no- internet area of Spitzbergen it is good to find new blogs from you! Best wishes from the Fishes also to your first mate and Spencer.

LikeLike

Fishes, many thanks. Just enjoyed catching up with your blogs this evening too. Absolutely envious of all that wildlife and scenery you are seeing – not that much wildlife here in the Baltic. I’ve pencilled in Svalbard for a future trip for us – we will see. Best wishes to you both from us three. (And the Heiks hook is still coming in useful!)

LikeLike