“You’d better get your passport out”, says the First Mate. “The Border Control officer is getting on the bus.”

We are on a bus to Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania. We had decided to leave Ruby Tuesday tied up in Riga, and spend a few days seeing what Vilnius was like. We had booked an AirBnB, cycled down to the Riga bus station, loaded the bikes in the luggage compartment in the bus, and found our seats. Next to the coffee dispenser, as it turned out. Now we are at the border between Latvia and Lithuania.

“I still don’t know why they need to have a border post here”, says the First Mate. “I thought all that was unnecessary now that both countries are in the EU.”

“Perhaps they are looking for Russians trying to get into Lithuania illegally”, I joke.

The Border Control official makes his way along the bus aisle looking at passports. We hand him ours, he has a perfunctory scan, and gives them back again. No issues, it seems. We breathe sighs of relief. The bus restarts and continues on its way to Vilnius.

I take the opportunity to read our trusty guide book about Lithuania.

“Humans have lived in the area since at least 9000 BC”, it tells me, “The Balts, whose ancestors had migrated from the region between the Black and Caspian Seas before 2000 BC, became relatively prosperous by trading amber. There were lots of different tribes, but in the 1200s, a local leader called Mindaugas unified them into one and created the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. One of his successors, Gediminas, then extended the borders down to present day Belarus and Ukraine. He also founded Vilnius in the 1320s, supposedly because he heard ‘an iron wolf howling with the voice of a thousand wolves’ which he took as a sign to found a city.”

“As you do”, I think to myself.

“Then in the late 1300s, one of the grandsons of Gediminas, Jogaila, decided to marry a Polish princess called Jadwega as a way of unifying the two countries against the Teutonic Knights”, it continues. “This eventually became known as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and was one of the largest countries in Europe at the time. By the 1500s, Vilnius was one of Eastern Europe’s most sophisticated and grandest cities.”

Outside, we are leaving the forest behind and enter extensive cropland with hectares of grain crops stretching into the distance.

“In the 1600s, Russia and its allies defeated the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and broke it up. Russia ended up with most of Lithuania, and clamped down hard on the rebellious Lithuanians. However, they weren’t able to quell the tide of national feeling, and in 1918, Lithuania declared independence. To complicate matters, Poland wanted to restore the commonwealth, and annexed Vilnius in 1920. The Lithuanian government fled to Kaunus, another city, where it stayed until WW2. Its history subsequently has been similar to that of Estonia and Latvia, with Russia invading in 1939, followed by the Nazis in 1941, and by the Russians again in 1944. Finally in 1991, it became independent from the USSR.”

“We’re nearly there”, says the First Mate, tapping me on the knee. “You’d better get ready.”

We arrive in Vilnius, unpack the bikes, and cycle to the AirBnB that we have booked.

“Here we are”, says the First Mate. “Number 11. Apartment 42 will be somewhere inside. Let me just open the gate to the courtyard with the code that the owner gave me.”

It had taken a little bit to find the street address, but we had managed in the end. Just as the First Mate is searching on her phone, a car appears on the other side of the gate. The gate opens noiselessly.

“Come on”, I say. “Quickly. No need for the code. We can go through the gate before it closes again.”

We push the bikes and ourselves through. The gate glides noiselessly shut again.

We climb the stairs in the stairwell to the fourth floor. There is no number 42.

“Perhaps it’s on the next floor?”, says the First Mate, climbing the stairs again.

Suddenly there is a piercing shriek. It’s the First Mate.

“There was a strange looking man behind the door to the landing”, she says, shaking. “I think he was deaf. He didn’t respond when I asked him if he knew where 42 was. He just kept staring into space like a zombie.”

“Perhaps we could ring one of the doors and ask if they know where number 42 is.”, I say.

We ring one of the doorbells. A woman in bra and panties opens the door.

“Sorry, no English”, she says, shutting the door again.

“Are you sure we are in the right block?”, I ask. “Something weird is going on.”

We go downstairs again and try to open the gate with the code. Nothing happens. We try several more times, but still nothing happens. After some time a young girl arriving home opens the gate from the outside.

“We are looking for apartment 42 in Block 11”, we tell her. “Do you know where it is?”

“This is Block 13”, she says. “Block 11 is the one over there.”

I try to give her the impression that I am a fire safety officer and that we are checking all the blocks in the street, but it fails miserably.

“Don’t worry”, says the young girl. “Lots of people make that mistake. Especially the older ones.”

We eventually find apartment 42 in Block 11. The code to the key box doesn’t work. We try several times but it refuses to open.

“I have just remembered that the owner sent another email to say that he just changed the code this morning”, says the First Mate after the seventh attempt. “Let me see if I can find it. Oh no, my phone is almost flat.”

She finds the email just before her phone batteries give one last gasp and give up completely.

The code works.

The next morning, we cycle into the city centre. On the way, we pass the derelict Soviet Palace for Culture and Sport. It’s hideous, so much so it has a strange kind of attraction about it.

We reach the Tourist Information.

“We don’t have free walking tours as such”, says the girl. “But we can give you a guidebook with a suggested route and lots of details of things on the way. That way you can see all the sights of the city.”

We start at the vast Cathedral Square and the Cathedral itself. Ironically (or perhaps not), it is built on an old pagan site that was used for worshipping Perkūnas, the Lithuanian God of Thunder, riding across the sky in his fiery chariot.

Perhaps alluding to Perkūnas is the imposing statue of Gediminas, the founder of Vilnius, and his horse.

In front of Gediminas’s statue a group of people are standing and waving the blue and yellow flags of Ukraine.

“We are Ukrainian refugees here in Lithuania”, explains one woman to us. “We come here once a week to give speeches and protest against the illegal Russian war against our country. Lithuanian people are very supportive of us as they remember what it was like for themselves to be occupied by the Russians. No one wants to go back to that.”

To one side of the Cathedral is the 17th century baroque Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania.

Exploring some of the narrow winding back streets, we come across Literatu Street with its plaques and writings of various famous writers with connections to Vilnius hanging on its walls.

The street gets its name because the Romantic writer and poet Adam Mickiewicz once lived there.

“The book says that he was the national poet of Poland because he wrote in Polish, but is also claimed by Lithuania because he lived here, and Belarus, where he was born”, says the First Mate.

“A bit inconsiderate of him not to think of the confusion he caused”, I say.

Vilnius is supposed to have more churches per hectare than any other city in Europe, and we can well believe it.

“You can’t show them all”, says the First Mate. “Just show one or two on the blog to give people an idea. Otherwise they will get bored.”

Further on are the University and Presidential Palace. The University was founded by the Jesuits in 1579.

We end up climbing to the castle on the hill dominating the city. The view from the ramparts is superb.

“Phew, all this sightseeing has made me hungry”, says the First Mate. “Let’s see if we can get a bite to eat. I want to try that cold beetroot soup that is so popular here.”

We find an open-air restaurant in the park near the Cathedral Square, and order Šaltibarščiai, the cold beetroot soup she is referring to. It is made from beetroot, gherkins, kefir, spring onions, and hardboiled eggs, all garnished with fresh dill and served with a side plate of warm boiled potatoes, and a slice of dark rye bread.

“Wow, that is so tasty”, I say, scaping the last vestiges of pink from my bowl. “Perfect for a light summer lunch. We must find the recipe and make it when we get home.”

“You’ve got a rye bread crumb on your beard”, says the First Mate. “Here, let me get it off.”

After lunch, we cycle over to Užupis on the other side of the Vilna River. Užupis was declared a separate republic from Lithuania in 1997.

“It all started as a bit of an April Fool’s joke”, explains the long-haired girl in the small boutique and coffee-shop. “Užupis had become somewhere that artists, poets and musicians liked to live, and one day some of them got together and came up with the idea of ceding from Lithuania and becoming an independent republic. So they elected one of them as president, others as the government, and wrote a constitution. Since then, it has captured the imaginations of people throughout the world who like the concept of escaping from the rat-race, and so it has become quite a tourist attraction. Now it is a source of pride to Vilnius city.”

We order two coffees and cinnamon rolls.

“We only have oat milk”, the Long Haired Girl says. ”Is that alright?”

Of course they do. But we are fine with that.

“The river is the border with the rest of Lithuania”, the Long Haired Girl continues, bringing the coffees to where we are sitting outside. “On Užupis Day, our national day on April 1, you can get your passports stamped, and use our national currency. We even have our own flag, the Holy Hand, which has an open hand on it to denote that corruption is not practised in Užupis. We did have an army of ten men, but we retired them a few years ago in the interests of peace. Besides, we have our own guardian angel. She protects us.”

We read that Užupis used to be the Jewish quarter of Vilnius, but the Holocaust obviously brought an end to that. During Soviet times, it became derelict, and only drunks, prostitutes and squatters lived there. But after Lithuania’s independence in 1991, artists and other creative people began moving in. The rest, as they say, is history.

“Did you see Tibet Square?”, the Long Haired Girl asks, as she collects the cups and plates. “The Dalai Lama came here and planted a tree there. The Chinese government weren’t too happy as they saw it as a political statement rather than a cultural one.”

There is a seat fixed in the middle of the river. We take turns sitting on it and taking photos of each other.

“Why are we doing this?”, I ask.

“I don’t know either”, says the First Mate. “But everyone else was doing it, so I thought that we had better too.”

It is our last day in Vilnius. The First Mate and I decide to split up and meet again for lunch. I set off for the National Museum of Latvia, while she heads for the MO Museum of Modern Art.

I spend a fascinating couple of hours learning about how people migrated from the Black Sea-Pontic steppe region at the end of the Neolithic period, bringing with them new languages, culture, farming methods, and tools. They decorated their pottery with cord impressions, used boat-shaped battle-axes, and domesticated livestock. The fusion of their culture with that of the existing inhabitants resulted in the Proto-Indo-Europeans and the emergence of the Balts.

Over time, these Balts evolved into different tribes with the exotically-sounding names of the Aukštaičiai, Selonians, Semigallians, Samogitians, Curonians, Sudovians, Skalvians and several others, each with different customs and rituals. It was only in the 1200s that they were reunified by Mindaugas.

“How was the MO Museum?”, I ask the First Mate over lunch.

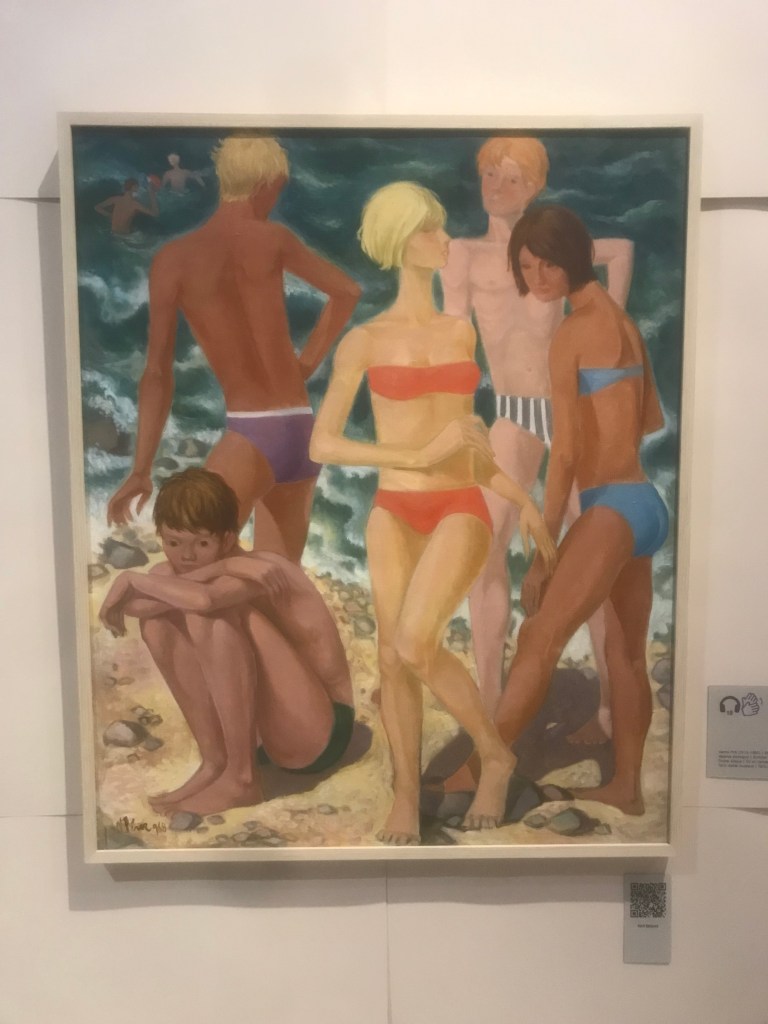

“There was an interesting exhibition there called ‘We Don’t do This’”, she tells me. “It was all about how sex and nudity in art was suppressed during the Soviet Union era, and the changes that have happened since independence. Sex was never mentioned in the public sphere under the Soviets, and there were severe penalties for doing so. For example, the artist of a painting of young people on a beach was jailed for six months. Can you imagine? Things are much more relaxed now. Art is more explicit and artists are much readier to explore love and intimacy than before. I found it quite fascinating.”

“We had better make our way to the bus station now”, I say. “It’s not long before the bus goes.”

We pay and jump on our bikes. Mine doesn’t feel quite right. The tyre is flat.

“It was fine when I arrived for lunch”, I say tetchily. “I wonder what caused that?”

“You’ll just have to push it to the bus station”, says the First Mate unsympathetically. “I’ll meet you there. I just have a bit more browsing to do. You can fix the bike when we get back to Riga.”

Seems to be much easier to navigate at sea than in a town ;)The baltics are still on our list. Best wishes from the Fishes.

LikeLike

Especially when the street numbering isn’t as good as it could be. Definitely recommend visiting the Baltic States – good sailing, nice people, beautiful scenery, and a fascinating but sad history. Best wishes from the Rubies!

LikeLike