“I’ll just go up to the hotel and pay the harbour fees” says the First Mate. ”Don’t forget to change the courtesy flag in the meantime. We’re back in Åland again. And you can put on the kettle. Gavin & Catherine are coming over for a cup of tea.”

We are tied up to the pontoon in the small harbour of Gullsviggan, having just arrived from Enskär in Finland. Our plan now is to head back to Stockholm, on the way exploring the northern parts of the Åland archipelago that we hadn’t had time to see when we were here in June on the Cruising Association rally.

I find the Åland flag in the locker downstairs and hoist it up to the starboard spreader. It adds a touch of colour to Ruby Tuesday.

I put the kettle on. Across the bay, not very far from the harbour, work is under way to build or renovate a bridge. A pneumatic drill on the end of a digger is breaking up the old road with loud staccato blows. Gavin & Catherine arrive, but we can hardly hear ourselves talk.

“I hope – bang-bang-bang-bang – all night”, says Catherine. “We’ll nev – bang-bang-bang-bang – sleep.”

“Pardon?”, I say. “What did you say?”

“Perhaps they knock – bang-bang-bang-bang – five”, says Gavin.

The pneumatic drill doesn’t knock off at five. Or six o’clock either. Only at seven does the noise stop. Peace descends.

“You don’t really appreciate silence until you don’t have it”, I say, trying to sound profound.

“I hope they don’t start too early in the morning”, says the First Mate.

‘Bang-bang-bang-bang!’, goes the drill at 0700.

“Couldn’t they have just waited until after breakfast, at least”, I say.

“Pardon?”, says the First Mate. “What did you say?”

We set off, heading southwards along the main fairway southwards through the Ålands.

“Look, there’s a huge cloud up ahead”, says the First Mate. “It looks like rain.”

“A real anvil-shaped thundercloud”, I say.

Sure enough, we see a squall approaching, and before long the rain is tipping down. Luckily the rain is almost vertical and I manage to keep dry under the bimini. There are dull rumbles of thunder overhead, the wind buffets us, and it is difficult to see our way to each marker buoy. I fight the wheel to keep on the same course, and hope that we don’t miss one and go aground on some hidden shoal. Then just as suddenly, it is all over. The clouds part, and the sun shines through again, bringing with it a warmth that makes the sudden squall a distant memory.

We arrive in a small bay to the south of the island of Barö, and drop anchor. To the east, we can still see the thunderclouds, but they are now past us and heading away. The wind has died down and peace descends.

“It’s amazing how quickly these squalls come and go”, says the First Mate over a cup of tea. “You would hardly believe that it was pelting down and the wind so wild just a short time ago.”

We cook dinner and sit in the cockpit watching dusk descend. A flock of geese fly overhead, their wing-strokes beating a steady rhythm. Over by the rocks on the shore, a pair of swans gracefully search for food. A fish breaks the surface of the water, making ripples that spread out in ever widening circles.

I pick up the book I am reading at the moment, The Soul of the Marionette: A Short Enquiry into Human Freedom, by John Gray. It’s a chaotic mish-mash of ideas drawn from several sources that in my mind don’t quite hang together in every case. His writing is not for everybody, and I am not sure I agree with it all either, but nevertheless it makes for some thought-provoking reading.

He makes the point that true freedom is not actually ‘freedom of choice’ but ‘freedom from choice’, in the same way that a marionette is free from having to make decisions about what it does because it is not self-aware. However, the human race has decided for itself on a different pathway to achieve this freedom of the spirit – by accumulating knowledge that allows us to manipulate the forces of nature. The endpoint of this, according to Gray, will be the ‘final chapter in the history of the world’.

At the moment, however, although we have made impressive technological advances, we are so far from understanding how we ourselves work and why we behave in different ways that this endpoint remains an almost unattainable aspiration. Instead, we content ourselves with illusions and cosy myths about who we are and the way the world operates. We are even prepared to die for the sake of these myths to give our lives meaning – religion, but also dreams of a new humanity with its concepts of communism, fascism, capitalism, democracy, and human rights. This is why conspiracy theories are so popular – they provide our lives with meaning that we are part of someone else’s plans.

But there are also risks with this progression towards an eventual state of perfection. Our knowledge allows us to create artificially intelligent machines, for example, which are making more and more of the decisions that used to be made by humans. While this frees us from the need to make choices, the risk is that these machines might eventually decide that humans are obsolete and that they should be destroyed.

It’s bleak stuff, and leaves me slightly depressed. I had read a previous book of his, Straw Dogs, in which he asserts that while humans have made considerable technological progress, we just go round and round in circles in terms of social organisation and governance. At first I had disagreed with this, but with the recent rise in autocracy and the far-right, I am starting to wonder if he might have a point.

It’s late and my brain is turning to mush. The First Mate has gone to bed. I switch off the lights and snuggle under the duvet to dream uneasily of the future.

We weigh anchor in the morning, and continue our journey eastwards. There’s almost no wind, and we have to motor for much of the way. It is warm and humid, and we pass through a swarm of small flies that cover the boat everywhere we look. They don’t seem to bite, but they are itchy and annoying when they land on our skin.

“It’s amazing how far out they come”, says the First Mate. “We can hardly see land, but they must have flown all this way.”

“They certainly weren’t carried out by the wind”, I say. “There isn’t any.”

But an hour or so later, a breeze springs up, and we manage to have a nice sail. The flies disappear.

“It seems as if they don’t like the wind much”, says the First Mate. “But I wonder where they have gone?”

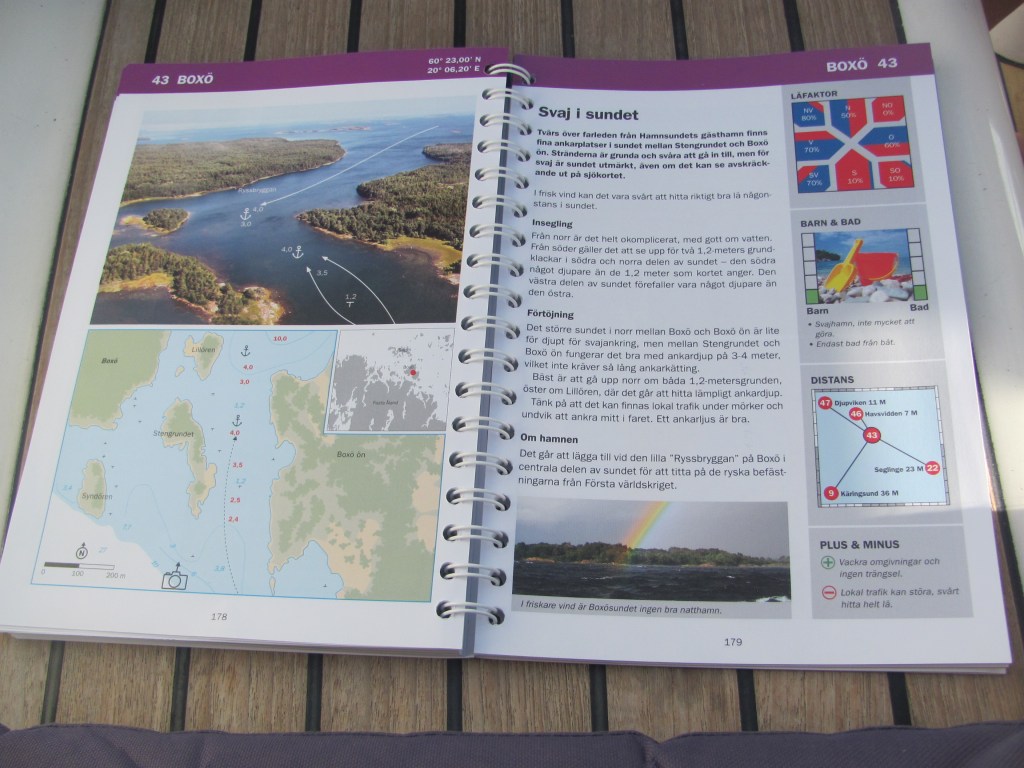

We decide to anchor in a sheltered bay on the island of Boxö, near a small islet at its southern end. The chart shows underwater cables running from one side to the other, so we need to take care not to anchor anywhere near them. We drop the anchor near the top of the bay, but by the time it digs in, we are too close to the small island.

“I think we need to reset it”, I call out to the First Mate at the bow. “It’s difficult to get it right – either we are too close to the cables, or we are too close to the island. Further out in the bay, it is too deep to anchor.”

We eventually manage to find a place, and settle down for the evening.

In the morning, we push on to Havsvidden, a small harbour in the north of Fasta Åland. The entrance is full of rocks, but there is a tight way in not much more than a couple of boat widths wide, and we need to thread ourselves past a nasty looking rock to starboard, and keep close to the rocky shoreline on the post side. It’s not an entrance for faint hearts. According to the harbour guide, there are supposed to be two markers to provide a leading line, but try as we might, we can only see one. There is nothing else to line it ap against.

But somehow we make it and find a tiny harbour able to accommodate around five boats. Saluté is already there, having entered first to test the depth. Another boat follows us in.

“We are from Turku”, one of her crew tells us as we tie up next to each other. “We were planning to get back today, but the weather forecast isn’t good, so we thought that we would put in here for the day and continue tomorrow instead. The sauna is supposed to be very good here.”

We go up to the hotel reception to pay.

“We are closing tomorrow”, says the girl at the front desk. “After that the hotel will be only open at the weekends until the end of September, then we close completely for the winter. But you are welcome to stay in the harbour. It is just that there won’t be any facilities available.”

“Another example of the weird holiday system they have here”, says the First Mate afterwards. “Look, there are still plenty of people at the hotel, and the weather is beautiful. Why on earth don’t they stay open?”

We decide to have dinner at the hotel in the evening. It’s a kind of farewell meal as Gavin & Catherine are leaving the next day to sail to Mariehamn to pick up a friend who is joining then for a week. We have decided to stay another day as the winds promise to be better on the following day, then head for Stockholm where we will meet our own friends, Hans & Gisela.

We choose a table in the enclosed balcony overlooking the sea. At the table next to us are two girls talking animatedly to each other. We try and work out what language they are speaking.

“I saw them earlier”, says Gavin. “I am pretty sure they are Russian. Not Finnish, at least.”

“I’m not sure”, says the First Mate. “It sounds more like one of the Baltic States languages. Perhaps Estonian.”

Before we can ask them, they finish their meal and get up and leave.

“I suppose a lot of the guests here are foreign”, I say. “But some of them must be Finnish. Do you think that you can tell who is Finnish or not just by looking at them? Is there a Finnish type?”

“Typical Finns have supposed to have blonde hair, blue almond-shaped eyes, round faces, and small round noses“, says Gavin.

I look around. Hardly anyone fits all those criteria. Most wouldn’t be out of place anywhere in Europe or Britain. Even in the Finnish towns we had visited earlier, I am not sure that I have seen many people that fit that type.

“I guess that, like anywhere, there has been a lot of mobility in recent years”, I say. “And people from all over have come to Finland to live.”

“If you are looking for other national characteristics, they also pride themselves on not mincing their words and being reserved, modest, humble, polite, and resilient”, continues Gavin.

“The Finns tell a joke that they are so reserved that when the distance rules were lifted after covid, they were really relieved to get back to normal as two metres was much too close to be next to another person”, says Catherine.

Gavin, Catherine and Saluté leave the next day. It’s sad to see them go. We had first met them on the Swedish island of Storjungbrun in mid-June, and had travelled with them more-or less since then. But we may see them again next year, as they are also planning to explore the Baltic States, war (or lack of it) permitting.

The hotel closes at 1100 on the dot, and the place is deserted by 1130. We are the only boat left in the harbour.

“It feels like a ghost town”, says the First Mate. “A bit weird after all the hustle and bustle at breakfast this morning.”

“Well, at least we can catch up on a few jobs that have accumulated”, I say. “I’m going to work on the blog.”

“And we can eat the fish that that little chap gave us”, she says.

A youngster had caught several perch from the pontoon the previous evening and had kindly given us his surplus.

We leave the next morning for Arholma in Sweden. The wind is from the southwest, and we have a pleasant sail for a couple of hours before dark clouds gather and the rain starts pouring down. Then we need to turn to the southwest and directly into the wind.

“I thought you said that the weather would be for good sailing today”, complains the First Mate from the cabin.

“Well, the forecast said it was going to from the south”, I say defensively. “I thought the angle would be good enough to be able to sail. But it looks like they might have got it wrong.”

We motor for a bit. Eventually the rain stops and the wind veers more to the south, allowing us to sail close-hauled for another few hours. We are about a mile from the Swedish coast when it stops altogether. We make it to Arholma under motor and anchor in the middle of the bay for the night.

“Familiar territory”, I say. “It feels like coming home somehow. We were here at the end of May. We’ve covered a lot of miles and seen a lot of places since then.”

“Look, even the birds remember us”, exclaims the First Mate. “They are welcoming us back.”

The next day, we push on towards Stockholm. We’ve booked in at a fibreglass repair company at a marina to the north of the city in a couple of days’ time for them to look at the damage to the bow. We sail down the main fairway for the ferries to the Åland islands and to Helsinki, and anchor in a small bay in Storön, an island in the archipelago not far from Stockholm.

We had chilled out here last year for several days, enjoying the good weather, reading, fishing, swimming and exploring in the small dinghy. It feels like coming back to a favourite place. Only one other boat is there, moored bows-to to the rocks on the shore and with a stern anchor.

“I thought we were going to have it to ourselves”, says the First Mate as we sip our glasses of wine and watch the sunset. “But at least they seem quite quiet. Perhaps they have gone ashore for a walk.”

In the morning, I notice that the other boat looks just the same as they night before. No one seems to be around. I peer through the binoculars. There is no sign of life.

“Perhaps they are just sleeping in”, says the First Mate.

“Perhaps they have died on the boat”, I say. “Murdered, even. How would we know?”

“You and you imagination”, she says. “Always looking for the dramatic.”