“There’s an empty berth over there”, calls out the First Mate from the bow. “Just on the other side of the boat with the black hull.”

We have just arrived in the town of Uusikaupunki on the Finnish coast, and are in the process of tying up at the city harbour.

I engage forward gear and aim the bow at the berth she is pointing to. As we enter, I move the gear lever to reverse to slow the boat and stop. Nothing happens! We keep moving forward.

“You’re going too fast!”, shouts the First Mate. “Slow down!!”

I wrestle with the lever and manage to get it into neutral. We are not going fast, but there is nothing to counter the forward momentum. There is a sickening crunch as we come to an abrupt stop against the wooden plank of the wharf.

“The throttle jammed somehow”, I shout back. “There was nothing I could do.”

There is a crack in the fibreglass of the bow.

“You’ll need to get that fixed”, says the man from the neighbouring boat. “And the throttle problem too. You’re lucky that there is a very good boatyard just on the other side of the river. They should be able to help you. I am happy to ring them and explain in Finnish what has happened, if you like.”

“We had a similar problem once”, says Gavin. “It turned out to be the clutch not disengaging. It was a big job to replace it, as the whole engine had to come out.”

It starts to rain heavily. Two men arrive from the boatyard, look at the bow, and stroke their chins thoughtfully. One starts the engine and puts the throttle lever into forward and reverse. The other goes downstairs and looks at the propeller shaft.

“They think that it is the propeller itself”, our neighbour translates. “The propeller shaft is rotating in the directions that it should for both forward and reverse. Do you know what sort of propeller it is?”

The propeller is a feathering one, meaning that when the boat is sailing, the blades rotate to line up with the direction of travel to reduce water resistance. When the motor is used, the centrifugal force causes the blades fly out to the angle of a normal propeller, with different configurations for forward and reverse.

“They think they need to lift your boat out and have a look at it”, says our neighbour. “You can take her over to their yard. It’s only ten minutes. But go very slowly, and try not to do anything that requires reverse. You can tie up alongside over there. They’ll help you.”

It’s not easy, knowing that you have nothing to stop forward motion except the friction of the water. Nevertheless, we manage to make it on one piece without hitting anything. A crane arrives, straps are slipped underneath Ruby Tuesday, and she is lifted out.

Sure enough, the propeller blades are stiff, and are not moving forwards and backwards as they should. They pump grease into the propeller body and manage to free it up.

“You can stay here for the rest of the day”, says the woman from the office. “Keep trying it in forward and reverse to see if you can replicate the problem. As for the crack in the bow, we suggest that you wait until you get back to Stockholm to get it fixed. We are too booked up at the moment. We’ll tape it up in the meantime to stop water getting in.”

We spend the rest of the day putting the gear lever in forward and reverse at periodic intervals. Everything works as it should. Despite my initial scepticism it does seem as if the problem is solved.

“We should at least see a bit of Uusikaupunki”, says the First Mate the next morning. “Why don’t we cycle in and have a look? We can have some lunch there, then sail for Enskär island in the afternoon.”

“Good idea”, I respond. “Apparently the Bonk Museum is worth a look.”

“Did you say the Bonk Museum?”, she says. “I am not sure that I want to see anything rude.”

“No, no”, I say hurriedly. “The Bonk Museum is a collection of weird and wonderful machines built by a Finn called Alvar Gullichsen. They are powered by anchovy oil. They look as if they should be really useful for something, but in fact have no purpose whatsoever. There’s a Paranormal Cannon, a Freakwave Transmuter prototype, and a Raba Hiff cosmic therapy dispenser, for example. Sort of the Finnish version of Heath Robinson, I suppose.”

We cycle into town and find the Bonk Museum. It is closed. Apparently it only opens at weekends at this time of year.

“We’ll just have to give it a miss”, says the First Mate. “We can’t hang around for another five days. Anyway, this looks like one of the machines here, just by the railway. That’ll have to do. ”

We have lunch at a nearby restaurant, then set sail. The propeller continues to work as it should.

We arrive at Enskär island and tie up alongside at the small pier. Gavin and Catherine are already there.

“We’ve just been talking to the harbourmaster”, says Gavin. “It’s an old pilot station, and has been in use since the 17th century. They still use it for that even now. He was on his way out to guide a large ship into Uusikaupunki. We passed it on the way. By the way, there is a grill place here just at the top of the pontoon. We could have a barbecue tonight.”

“Good idea”, I say. “We still have some charcoal left. I’ll see if I can find it.”

As I walk along the pier, I pass a young man in his early twenties tinkering with the engine of a small boat tied up alongside.

“There’s a problem with the fuel”, he explains. “It keeps cutting out. I have just come over from Uusikaupunki.”

“That’s quite a way in a small boat”, I say. “Fourteen miles or so. We have just sailed out from there.”

“I am actually from Turku in southern Finland”, he says. “But I have a job on a tall ship at the moment. You might have seen it in Uusikaupunki? I borrowed this boat to come to visit friends who are working here on Enskär. They don’t know I have come, and I have to find them.”

“Good luck”, I say, wondering why he hadn’t contacted them first.

“It’s his girlfriend”, Catherine tells us later. “She is one of the summer workers on the island. Apparently it’s her birthday today, and he wanted to surprise her.”

“Who says romance is dead?”, says the First Mate.

“He has very fine features”, says Catherine. “Almost feminine. He reminds me of that Greek god Adonis.”

“I hope he doesn’t get gored by a wild boar”, I say. “You never know what might be on this island.”

We light the fire. Before long, the charcoal is burning away merrily. Soon there is the aroma of cooking steaks and sausages.

The conversation turns to the news of the day.

“Did you hear that it has been announced that Prigozhin, the Wagner boss, has been killed”, says Gavin. “Apparently, the plane that he was travelling to St Petersburg crashed. They don’t know yet if it was an accident or whether it was deliberate.”

“If you ask me, I think I know which one it was”, says the First Mate. “It’s too much of a coincidence to be an accident.”

“I am not surprised”, I say. “I was wondering how much longer he would have after that aborted march on Moscow a few weeks ago. What I don’t understand is why he didn’t see it coming. He might have been a bit safer if he had stayed in exile in Belarus, but to go back to Russia as if nothing had happened doesn’t make sense. I wonder how it will affect the war in Ukraine?”

“I don’t expect it will make much difference”, says Catherine. “After all, most of the Wagner troops have been withdrawn from Ukraine now anyway. My guess is that they’ll just be absorbed into the regular army.”

The mosquitoes have now arrived in force, and the flow of conversation is punctuated by continual slapping as we try in vain to protect ourselves from being bitten.

“Time to get back in the boat”, says the First Mate. “Unfortunately, I react badly to mosquito bites. They’ll all be swollen up by the morning.”

As we climb into bed, there is the sound of voices outside, then the noise of an outboard engine starting. I peer out of one of the windows into the darkness. In the pool of light from the single lamp of the pontoon I see Adonis saying goodbye to his Aphrodite. He roars off into the darkness, and she walks slowly back along the path to the lighthouse.

“It looks like he is heading back to Uusikaupunki”, I say. “It’s not something I would like to do at this time of night with all those rocks and reefs in the way.”

“He probably knows the area like the back of his hand”, says the First Mate.

In the morning I wake early, make myself a cup of tea, and sit on deck watching the reds and yellows as the sun peeps above the horizon to start its daily journey. The sea is calm, only the occasional lap of a wavelet as it washes over the rocks of the breakwater. I decide to go for a walk to the other side of the island before the others get up. I follow the rough track along the shoreline, passing a tiny sandy beach before turning towards the centre of the island. To my right, on the higher ground overlooking the beach, is an imposing looking house which I learn later is the old pilot house. Nowadays it is rented out to holidaymakers visiting the island.

Rounding a corner, I am surprised to be met by a bare-footed woman in her dressing gown, picking her way carefully through the stones of the track.

“I am just going for my morning swim”, she says, almost apologetically. “I have been doing it for 30 years, every day that I have been living on this island. I live in one of the houses near the lighthouse.”

“It must be cold”, I say.

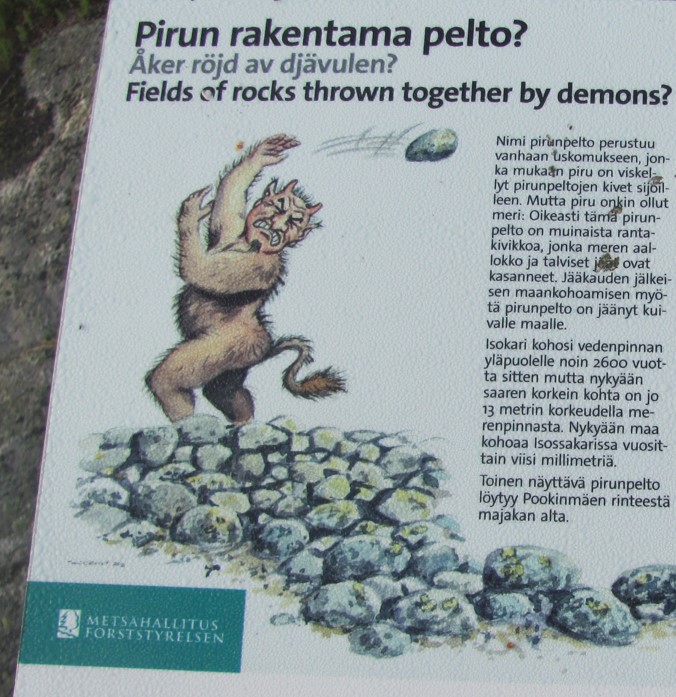

“It gets cold in the winter, that’s for sure”, she answers. “But at this time of year it is beautiful. By the way, you should have a look at the demons’ fields over there. The local people used to call them that, as they believed that the piles of rounded stones were gathered by evil spirits. In reality they were piled up by waves and ice on former beaches that have risen due to land uplift. The whole island was still under water only 2,500 years ago.”

We carry on in our respective directions. Shortly after, I come across my second surprise of the morning – a gun emplacement, the barrel of the gun aimed eastwards. Not quite what one might expect on a quiet little island.

“All the civilians were cleared from the island in 1941”, a placard tells me, “and the gun and an ammunition store were built by the Finnish Defence forces to prevent enemy landings by sea. But there was no military action on the island, and the civilians were allowed back in 1945. Then in the 1970s, a watch tower was built to help direct artillery fire against enemy ships. Nowadays, the tower is used by ornithologists to spot birds on the island. You can visit all three at your own risk.”

No prizes for guessing who the enemy might be in both cases.

Eventually I reach the lighthouse, surrounded by a cluster of former lighthouse keepers’ cottages. Built by the Russians in 1838 after Finland became a Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire, it was designed to develop a new sea route independent of the Swedish ones and to project Russian power and prestige westwards, similar to the Post Office that we had seen in June at Eckerö on Åland. At nearly 50 m in height, it is the tallest lighthouse in the Gulf of Bothnia. It is still operational, but is now fully automated, and the cottages are privately owned and used as summer retreats.

“Apparently the lighthouse was nearly blown up in WW2”, says Gavin over a coffee later. “The Finns thought that it would act as a landmark for Russian bombers, so they laid explosive charges in the base. Then they realised that the debris from the explosion would probably be an even greater landmark, so it was left as it was.”

“It would be a pity if they had destroyed it”, I say. “It’s pretty impressive.”

“Did you hear Adonis leave last night?”, asks Catherine, changing the subject.

“We did”, says the First Mate. “But we wondered why he didn’t stay the night.”

“He had to get back to work in the morning”, says Catherine. “I was talking to his girlfriend this morning. She was the one that collected our marina fees. She was overjoyed to see him, but rather distraught that he couldn’t stay. Ah, young love!”

We return to Ruby Tuesday and prepare to leave.

“Do you realise just how much of your blog is about the Russians?”, says Spencer to me as I roll up the side panels.

“They certainly had a major influence in the Baltic”, I answer. “And on Finland in particular. It must be difficult to live next to a large, powerful, often hostile, neighbour.”

“You know, I read something interesting about them the other day”, he says. “Of course, we all know that they have a tradition of autocratic rulers – Peter the Great, Catherine the Great, Lenin, Stalin, and now Putin – and they seem to have the mindset that politics is best left to these rulers. But I read also that some of their autocratic leanings are because Russians see themselves as the only true keepers of Christian traditions.”

“You mean the Russian Orthodox Church?”, I ask.

“Yes”, says Spencer. “The first capital of Christianity was Rome, right? But around 330 AD, Constantine abandoned Rome and moved his capital to the newly-built city of Constantinople. That became the ‘Second Rome’. In the Byzantine Empire which followed, church and empire became so inextricably entwined that people couldn’t imagine Christianity without an emperor. That state of affairs lasted more than 1000 years, but Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453. The Christian traditions practised there survived in the Russian Orthodox Church which adopted Moscow as its centre. Moscow was subsequently promoted as the ‘Third Rome’.”

“And Russia has the sacred mission of preserving Christianity on Earth, I suppose?”, I say.

“Correct”, says Spencer. “That’s why they are quite comfortable with autocracy. Russians see their leaders as divinely chosen by God and charged with keeping the Christian flame burning. Unlike in Western Europe, in Russia any independent thinking, religious or otherwise, was condemned. It also explains why the Russian Orthodox Church is so supportive of the war in Ukraine.”

“Preventing an Orthodox neighbour from falling into the hands of the evil, heretical West”, I say. “It certainly explains a lot.”

The First Mate appears at the companionway.

“Come on”, she calls out. “That’s enough talking to that spider. We need to sail on to the Ålands. The others have already left.”